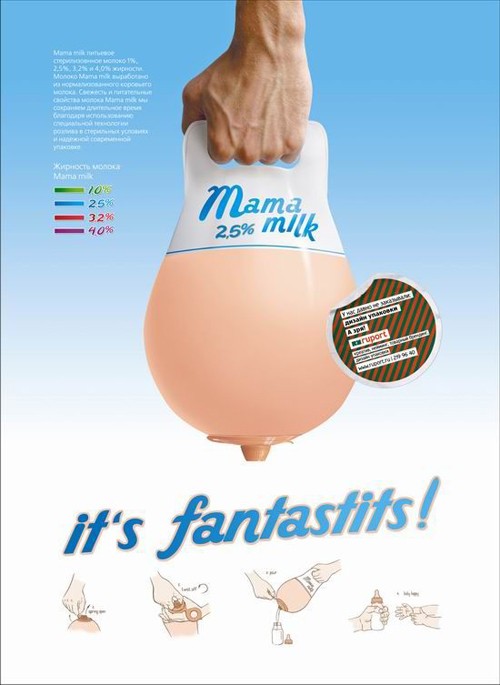

One of our very first posts on SocImages was a Wrestle Mania billboard. It featured a bunch of muscle-bound men without shirts, but their nipples were photoshopped out. They were too suggestive of women’s nipples (which are obscene, obviously) and possibly against the law.

Nipple-phobia is back with a particularly amusing example from Facebook. Company policy requires deleting images of “female nipple bulges” (defined as “naked ‘private parts'”; male nipples, with or without bulges, are excluded from the ban). This prompted Facebook to take down a New Yorker cartoon by Mick Stevens, see if you can figure why.

Robert Mankoff mocked the incident.

To be fair, and here I begin my own mockery, we are talking about Eve here. And she had lost her innocence — and the innocence of the entire human race — with her “original” idea. So… you know, she was a dirty, dirty gal who did a bad, bad thing and would realize the importance of covering up those “dirty pillows” sooner or later. Facebook was just ahead of the curve. I guess.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.