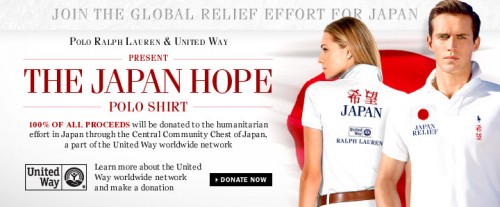

From the blog Japan Probe I discovered that Ralph Lauren has partnered with the United Way to create a line of polo shirts they’re calling Japan Hope:

The shirts range from $98-110, and the website says “100% of all proceeds” will be donated to humanitarian efforts in Japan. The site does have a link to a United Way site that lets you make donations directly, without buying a shirt. However, looking over the information about the Japan Hope shirt, I have the same concerns I often do when I see humanitarianism-through-consumption efforts. Though we’re assured that “100% of all proceeds” will be donated, nowhere could I find out what that actually adds up to. Perhaps the donation from each shirt is sizable, but it may just as well be tiny. There’s no way to know what your actual contribution to Japanese relief efforts is. If you wanted to donate $50 and you buy this shirt, have you met your donation goal?

I honestly don’t really understand the point of these types of products. If you want to help out, why not just donate directly to a group involved in relief efforts? Why the need to get something for yourself in return? Maybe I’m underestimating the draw; perhaps such gimmicks actually bring in donations (of whatever size) from individuals who otherwise wouldn’t have contributed anything at all. (If any of our readers have any direct evidence one way or the other, I would love to hear about it.)

But I would feel more comfortable with this type of consumption-based giving if the companies engaged in it clearly provided a baseline idea of what the “proceeds” would be so consumers could have some sense of the size of their contribution. Without such information, I can’t help but wonder how many people greatly overestimate the positive effects of their purchase.

For more on potential problems with buying-as-activism, see my earlier post on the ethical fix.