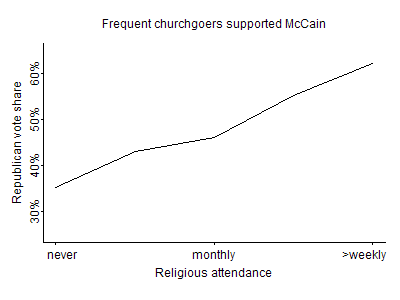

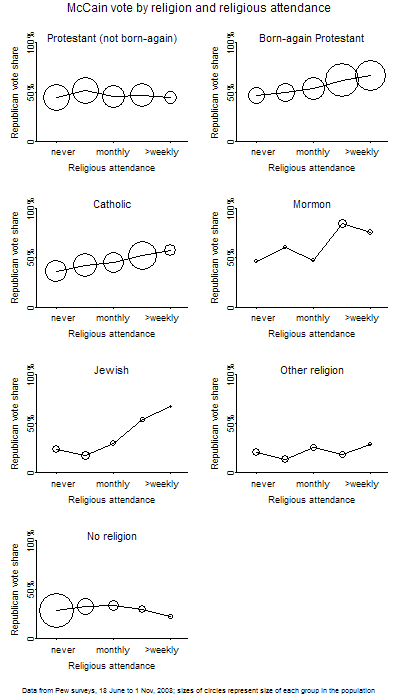

Andrew over at FiveThirtyEight posted about the association between religious attendance and voting behavior. Looking at the 2008 Presidential election, Pew data indicates that frequency of religious attendance is strongly related to likelihood of voting for McCain:

But looking more closely at the data, we can see that the relationship is more pronounced for some groups, such as born-again Protestants and Catholics, than others, such as non-born-again Protestants:

From the original post over at FiveThirtyEight:

The size of each circle is proportional to the number of people represented in the survey. In particular, most of the people who attend church more than weekly are born-again Protestants.

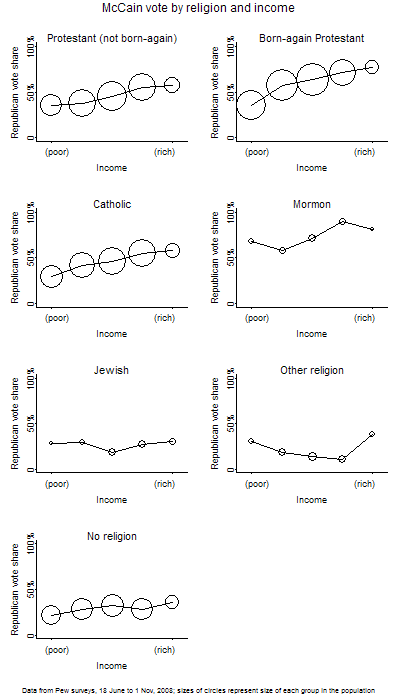

Another interesting thing to look at is the how income interacts with religion to influence voting patterns. These graphs show the McCain vote by income among various religious groups:

Notice that among Jews and the non-religious, increased income didn’t substantially increase the chances of voting for McCain (and those in the “other” category are just confusing). For these groups, being rich doesn’t appear to have been enough to draw them to McCain, whereas for most Christians we see a clear trend: the richer adherents were, the more likely they were to vote Republican. Both Jews and non-adherents started out much less likely to vote for the Republican ticket, and their opposition was strong enough that it trumped what we would expect to see if people voted on a narrow interpretation of self-interest (i.e., “I make $300,000 and Obama says he’ll raise income taxes on incomes above $250,000, so I’ll vote for the other guy”). Presumably Republican positions on social issues, or close association with evangelical Christians, put off some wealthy non-religious and Jewish voters who might otherwise be likely to vote for them based on fiscal policy, but that’s just a guess, since we don’t have data here on voters’ explanations of their candidate preferences.