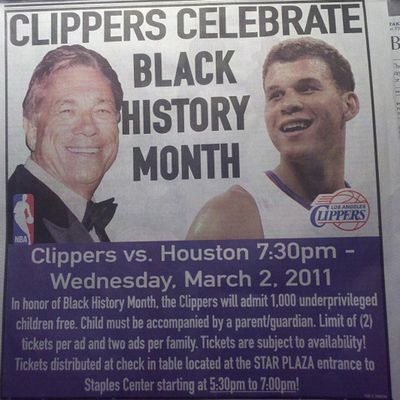

Jamal Spencer, a student in Naomi Glogower’s sociology class at Michigan State University, sent in the following promotion for Black History Month, courtesy of the Los Angeles Clippers (source):

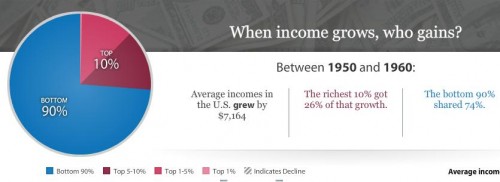

Spencer makes two interesting points. First, Black History Month is in February. Oops. Second, and more importantly, notice that the promotion includes admitting “1,000 underprivileged children free.” It is assuming that “Black” is coterminous with “underprivileged,” erasing middle and upper class Blacks and poor Whites. In fact, about half of poor people are White and about 75% of Black people are not poor. This promotion, however, strengthens the conception that the poor are Black, a conception that contributes to the (racist) maligning of and restriction of benefits for the poor. Happy Black History Month indeed.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.