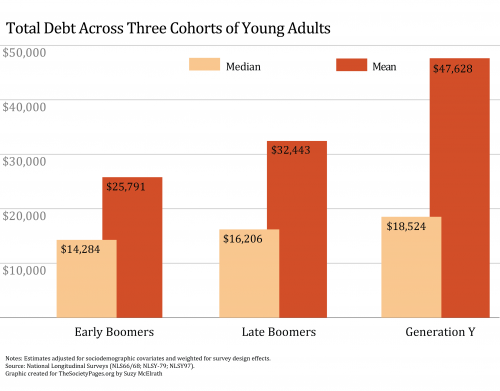

In the lasts 15 years, student debt has grown by over 1,000% and the debt held by public colleges and universities has tripled. Where is the money going?

The scholars behind a new report, Borrowing Against the Future: The Hidden Costs of Financing U.S. Higher Education, argue that profit is the culprit. They write:

Scholars have offered several explanations for these high costs including faculty salaries, administrative bloat, and the amenities arms race. These explanations, however, all miss a crucial piece of the puzzle.

Sociologist Charlie Eaton and his colleagues crunched the numbers and found that spending on actual education has stagnated, while financial speculators have been taking an increasing amount of money off of the top.

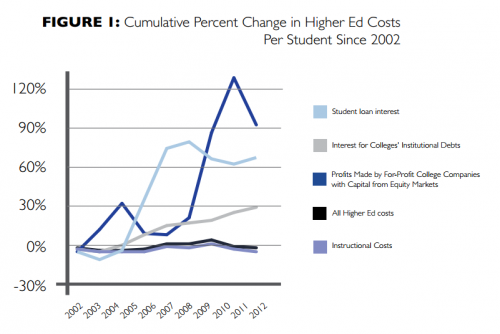

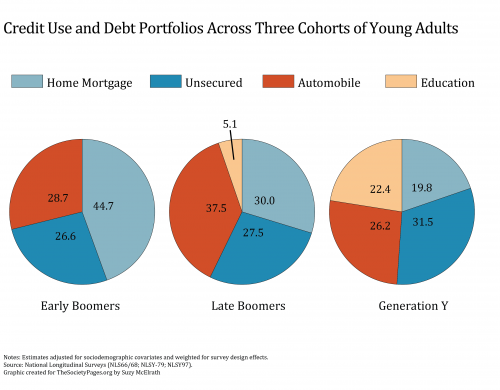

Higher education fills the pockets of investors in three ways:

- Interest on student loans, paid by students and parents.

- Interest paid by colleges who take out loans to fund projects — everything from new academic buildings to luxury dorms and stadiums — ultimately repaid with tuition hikes and higher taxes.

- And profit from for-profit colleges (with “dismal graduation rates, by the way).

Take a look at this figure breaking down the sources of the rise in the cost of higher education. Interest on debt — taken on by both students and the colleges they attend — has risen. Meanwhile, direct profits from for-profit colleges have skyrocketed.

Overall, Eaton and his colleagues found that Americans are spending $440 billion dollars a year on higher education and that 10% of that goes into the pockets of investors who are skimming profit off of all forms of higher education.

Want more? Read their report or watch their summary:

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.