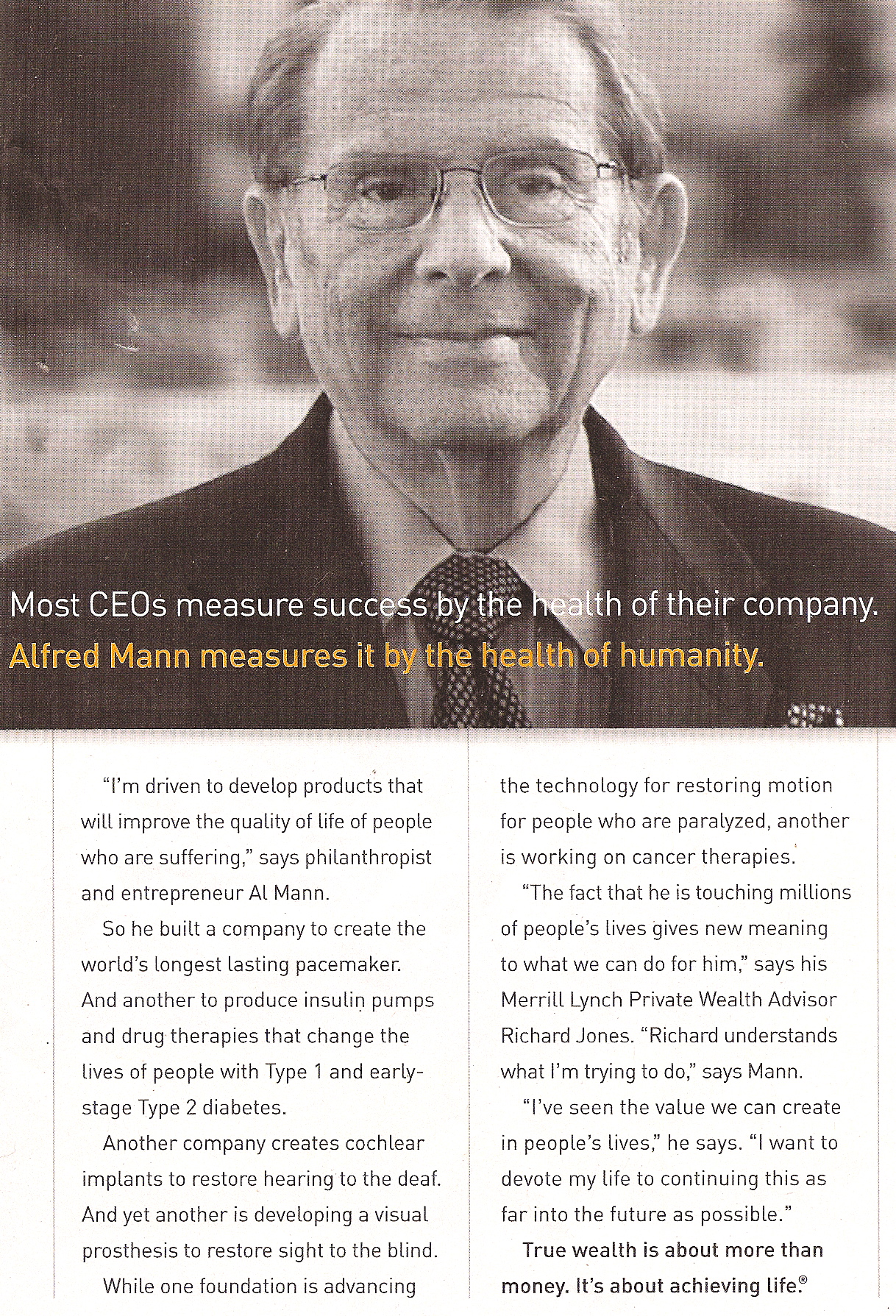

I found this Merrill Lynch ad in The New Yorker last week:

What I found interesting about it was the text, which is talking about how the guy in the photo is a philanthropist. Examples of his products to “…improve the quality of life of people who are suffering” include better pacemakers, insulin pumps, a visual prosthesis for the blind (who knew?), and cochlear implants for the deaf. The reason it drew my attention is that while (to my knowledge, anyway) pacemakers and insulin are generally accepted as useful technologies that improve people’s lives, cochlear implants have been the subject of controversy. Many people in the deaf community argue deafness is not a “disease” or a “disability,” but simply a state of being (or a subculture), and that efforts to “correct” deafness are offensive and even culturally oppressive (for an example of this perspective, see this discussion from the Drury University website). Thus, while most people would see efforts to treat diabetes as an unequivocal good, and few diabetics would oppose them, opinions about cochlear implants are much more divided, and those who would presumably be seen as the beneficiaries of this technology are not necessarily convinced they need it or that there is anything “wrong” with them that requires intervention. In fact, within the deaf community individuals may face peer pressure to reject implants and those who get them are sometimes stigmatized as sell-outs, basically.

It might be a useful image for sparking a discussion about the social construction and definition of medical problems. Who gets to decide whether a condition is a disease or is just a human characteristic (that is, perhaps uncommon but not automatically problematic)? What if the individuals who have the characteristic disagree with the wider public (or among themselves) about its interpretation? You might use it to spark a discussion about medical interventions and ethics–what are the implications of the increasing ability to use medical innovations to alter a wide variety of characteristics? Are innovations such as cochlear implants helping improve the lives of those who cannot hear, or are they simply reinforcing the idea that deafness isn’t “normal” and thus should be treated as a medical problem? And why does resistance to medical intervention arise surrounding some issues, such as deafness, but not others (for instance, as far as I know, there isn’t the same level of controversy surrounding blindness)?