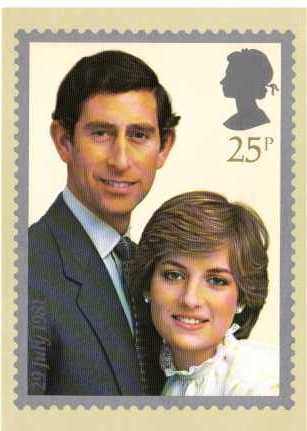

A quick Google image search suggests that Prince William and the to-be Princess Duchess of Cambridge Kate Middleton conform to Western culture’s expectation that a man be sufficiently taller than his woman. Not so for Prince Charles and Princess Diana. In light of today’s royal nuptials, I thought I’d re-post this fav of mine. Originally cross-posted at Jezebel.

In the U.S. and the U.K., one of the most unbreakable rules of mating involves height. He must be taller than her, preferably significantly taller. Men and women often pick one another in such a way that any given couple follows this rule even if, given random assortment, some couples would involve women who the same height or taller than their male partners.

Rumor has it, though I can’t prove it, that Hollywood routinely puts leading men in platform boots or on stools so that they appear appropriately tall relative to their leading ladies.

Philip Cohen, however, alerted me to a case that can be nicely shown: Prince Charles and Princess Diana. As these photographs show, Charles was about the same height as Diana, perhaps even shorter.

When Charles and Diana were posed together formally, however, they were typically arranged so as to suggest that he was significantly taller than her, or at least to disguise the fact that he was not.

A photo from their engagement announcement with Charles on a step behind her:

(BBC)

(BBC)

And more:

This effort to make Charles appear taller is a social commitment to the idea that men are taller and women shorter. When our own bodies, and our chosen mates, don’t follow this rule, sometimes we’ll go to great lengths to preserve the illusion.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

(

( (

(