Cross-posted at Adios Barbie.

Today I had the pleasure of reading a 1978 essay by Susan Sontag titled The Double Standard of Aging. I was struck by how plainly and convincingly she described the role of attractiveness in men’s and women’s lives:

[For women, o]nly one standard of female beauty is sanctioned: the girl.

The great advantage men have is that our culture allows two standards of male beauty: the boy and the man. The beauty of a boy resembles the beauty of a girl. In both sexes it is a fragile kind of beauty and flourishes naturally only in the early part of the life-cycle. Happily, men are able to accept themselves under another standard of good looks — heavier, rougher, more thickly built. A man does not grieve when he loses the smooth, unlined, hairless skin of a boy. For he has only exchanged one form of attractiveness for another: the darker skin of a man’s face, roughened by daily shaving, showing the marks of emotion and the normal lines of age.

There is no equivalent of this second standard for women. The single standard of beauty for women dictates that they must go on having clear skin. Every wrinkle, every line, every gray hair, is a defeat. No wonder that no boy minds becoming a man, while even the passage from girlhood to early womanhood is experienced by many women as their downfall, for all women are trained to continue wanting to look like girls.

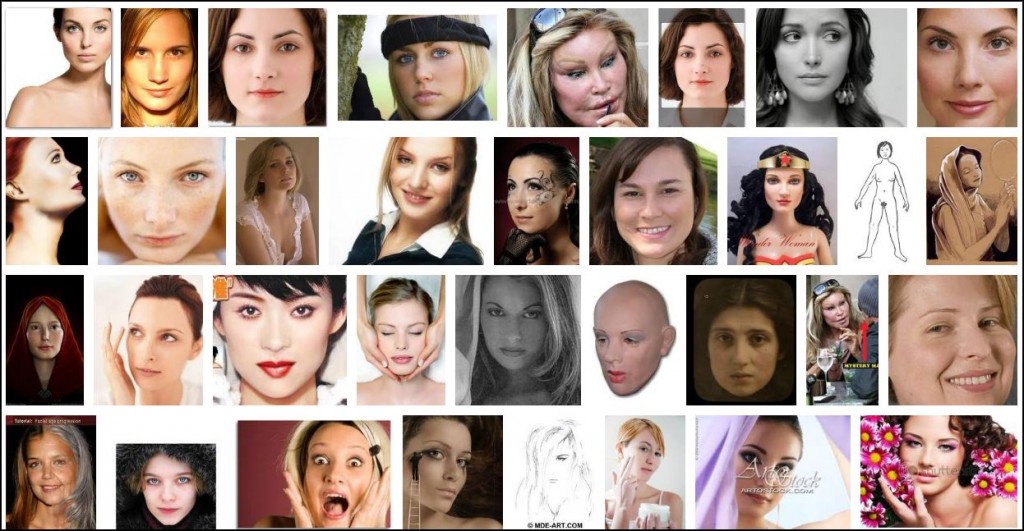

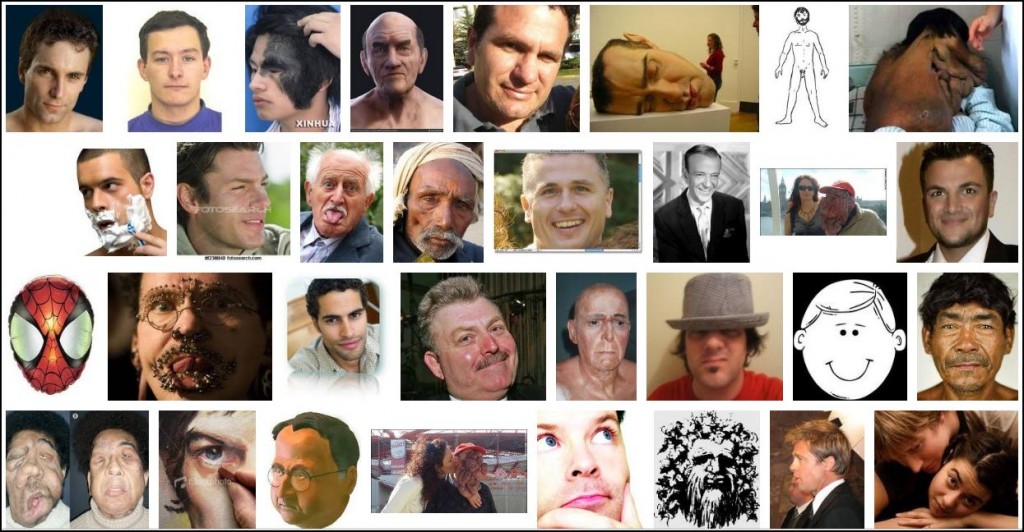

These words reminded me of an idea for a post submitted by Tom Hudson. Tom was searching for faces to help him draw and was struck by the differences in the results for “woman face” and “man face”:

The wide variety of men’s faces, compared to the overwhelming homogeneity of the women’s faces, nicely illustrates Sontag’s point. Women’s faces are important and valorized for only one thing: girlish beauty. Men’s faces, on the other hand, are notable for being interesting, weird, wizened, humorous, and more.

On another note, the invisible but near total dominance of whiteness is worth acknowledging.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.