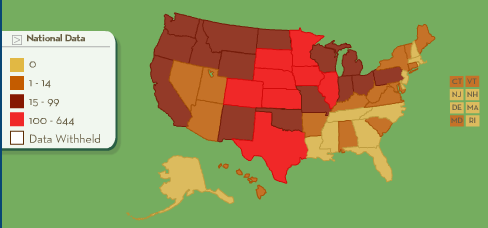

Food & Water Watch has an interesting interactive map that allows you to click on states and see how many factory farms it has per county, broken down into cattle (meaning beef, I assume), hogs, dairy, broilers, and layers (the last two are both chickens). You can look at number of facilities or number of animals. Here’s a screenshot of the number of cattle containment facilities in the U.S.:

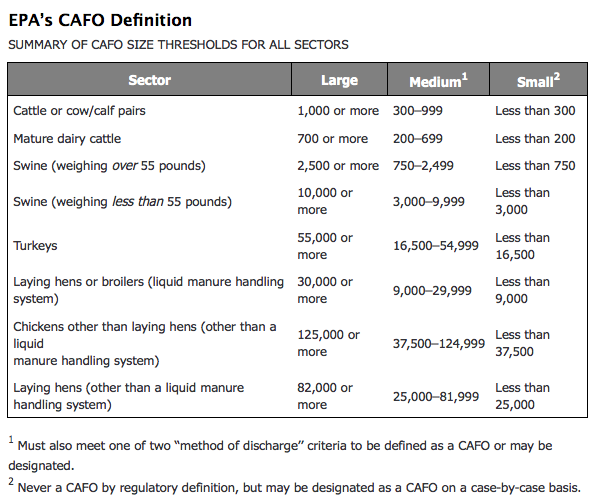

Factory farms were identified using Census of Agriculture data and counting those that “best match the Environmental Protection Agency’s definition for a confined animal feeding operation…” based on the following guidelines:

There’s a very detailed description of the methodology available here and an explanation of the maps here.