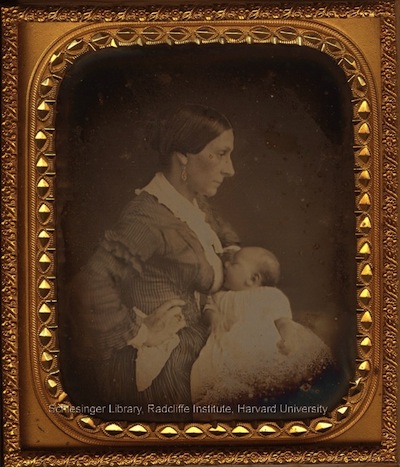

My sister-in-law Charlotte was recently loudly admonished by a flight attendant on an international flight for allowing her “breast to fall out” after she fell asleep while nursing her baby. A strong advocate for breastfeeding, Charlotte has shared with me her own discomfort with public breastfeeding because it is considered gross, matronly, and “unsexy.”

I heard this over and over again from women I have interviewed for my research: Women who breastfed often feel they have to cover and hide while breastfeeding at family functions. As one mom noted, “Family members might be uncomfortable so I leave room to nurse—but miss out on socializing.” This brings on feelings of isolation and alienation. Because of the “dirty looks” and clear discomfort by others, women reported not wanting to breastfeed in any situation that could be considered “public.”

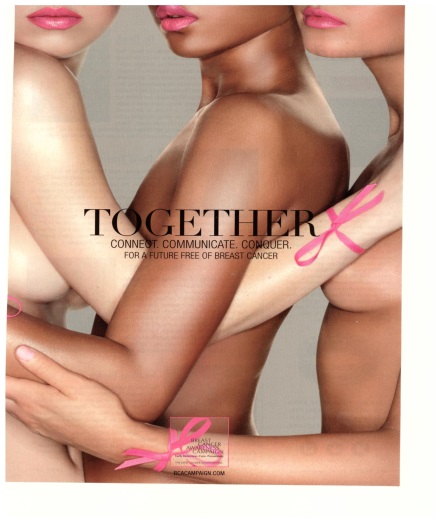

Meanwhile, I flip through the June 2012 issue of Vanity Fair and see this ad:

We capitalize on the sexualization of the breast to raise awareness about breast cancer. Yet, we cringe at the idea of a woman nursing her child on an overnight flight.

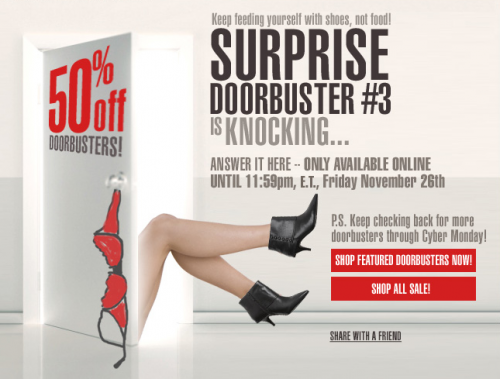

What’s happening here? These campaigns send contradictory messages to women about their breasts and the way women should use them, but they have something in common as well: both breastfeeding advocacy and breast cancer awareness-raising campaigns tend to reduce women to body parts that reflect the social construction of gender and sexuality.

Breast cancer awareness campaigns explicitly adopt a sexual stance, focusing on men’s desire for breasts and women’s desire to have breasts to make them attractive to men. Breast milk advocates focus on the breast as essential for good motherhood. Breastfeeding mothers sit at the crossroads: Their breasts are both sexualized and essential for their babies, so they can either breastfeed and invoke disgust, or feed their child formula and attract the stigma of being a bad mother.

Both breastfeeding advocacy programs and breast cancer awareness-raising campaigns demonstrate how socially constructed notions of ownership and power converge with the sexualization and objectification of women’s breasts. And, indeed, whether breast feeding or suffering breast cancer, women report feeling helpless and not in control of their bodies. As Jazmine Walker has written, efforts to “help” women actually “[pit] women against their own bodies.”

Instead, we need to shift away from a breast-centered approach to a women-centered approach for both types of campaigns. We need to, as Jazmine Walker advocates, “teach women and girls how to navigate and control their experiences with health care professionals,” instead of pushing pink garb and products and sexualizing attempts to raise awareness like “save the ta-tas.” Likewise, we need to support women’s efforts to breastfeed, if they choose to, instead of labeling “bad moms” if they do not or cannot. Equipped with information and bolstered by real sources of support, women will be best able to empower themselves.

Jennifer Rothchild, PhD is in the sociology and gender, women, & sexuality studies departments at the University of Minnesota, Morris. She is the author of Gender Trouble Makers: Education and Empowerment in Nepal and is currently doing research on the politics of breastfeeding.