Jeremiah sent in a fascinating post by Nicola at edible geography about how Prohibition, which outlawed liquor in the U.S. from 1920-1933, changed our culture in a number of ways that aren’t immediately apparent. Nicola draws heavily on historian David Okrent’s book Last Call.

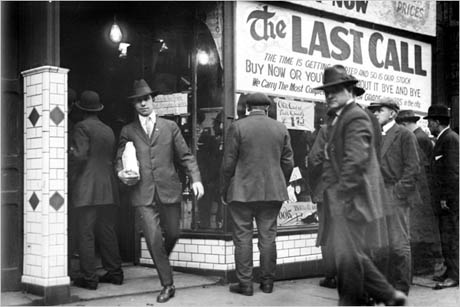

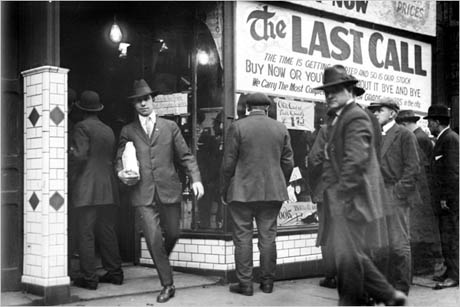

An image from Detroit the day before Prohibition went into effect in 1920:

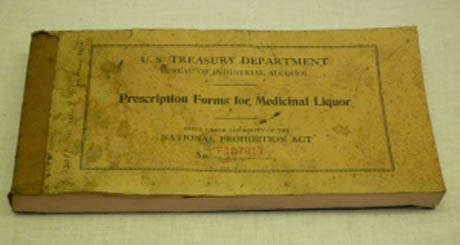

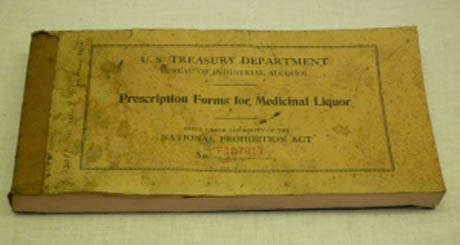

Although Prohibition made liquor illegal, there were a number of loopholes, including certain alcoholic “fruit juices” (which in effect meant wine and hard ciders were often allowed), medicinal uses of alcohol, and industrial alcohols. Nicola provides an image of a prescription booklet for medicinal alcohol:

These loopholes led to a dramatic rise in the popularity of wine in the U.S.: “American wine consumption increased from 70 million gallons in 1917 to 150 million gallons in 1925,” according to Nicola. That change affected the agriculture of California, in particular, where many acres of other crops were replaced with wine grapes. In another unexpected consequence, Okrent argues that the medicinal use loophole was a central factor in the success of drugstores such as Walgreen’s, since sales of alcohol for medical purposes were very profitable.

Prohibition also affected international maritime laws. At that time nations controlled the areas up to three miles off their shores. Along much of the U.S. coast, “Rum Rows” emerged, strings of generally foreign-owned ships anchored just outside the 3-mile jurisdiction limit, all full of liquor. They would openly advertise prices. This is an image of the Kirk and Sweeney loaded with illegal alcohol in 1924 (via):

The U.S. Coast Guard has a collection of images of its efforts to stop the illegal importation of liquor. This image shows one of the small rum runner boats that would sail from the shore to Rum Row to load up on alcohol, as it approaches a British-owned boat called the Katherine in 1923:

Nicola describes the scene:

…a floating ship-city, thousands of miles in length, bobbing up and down in place along the coast of America, and serviced by a fleet of much smaller, nimble rum runners that slipped to and from the mainland under cover of night.

The U.S. government began to push for an extension of the area of the ocean over which governments have jurisdiction, from 3 miles to 12, which would make it much more difficult, time-consuming, and dangerous to run liquor in from the larger ships. The U.S. eventually succeeded in pushing its national borders outward, expanding national sovereignty over oceans, another unexpected consequence of our anti-alcohol policies. Rum Row dutifully relocated farther offshore.

Apparently Prohibition also fueled the popularity of mixed drinks (the mixers helped mask the smell and often unpleasant taste of bootleg liquor) and dinner parties (since you couldn’t buy liquor openly at restaurants but were relatively safe serving it in your home). According to a set of Life photos about Prohibition, sales of Coca Cola tripled, since soda served as both a substitute and mixer for alcohol:

From the Life photoessay:

“People don’t realize,” Okrent told LIFE.com, “how much drinking there was in this country before Prohibition. We were awash in booze. In 1830, for example, the per capita consumption of alcohol was three times what it is today — 90 bottles of booze per year per person over the age of 15. By 1933, drinking was around 70 percent of pre-Prohibition levels, and with some fluctuations has stayed well below pre-Prohibition levels ever since.

Okrent says that contrary to what we often see in movies, where speakeasies are built to be easily dismantled or disguised as legal businesses in case the cops raided, by the late 1920s, many speakeasies were set up as permanent structures that were clearly serving liquor, and customers felt fairly secure going to them:

As soon as liquor became legal again, Americans enthusiastically returned to openly buying and selling it, though, as Okrent said, not at pre-Prohibition levels (photo from a different Life photoessay):

The Budweiser company decided to deliver beer to several high-profile locations by horse-drawn cart as a marketing stunt, giving us the iconic Budweiser Clydesdales. Here they are on their way to the Empire State Building:

And if you buy Okert’s argument, Prohibition even gave us NASCAR; he says it emerged in the South after Prohibition ended, when all the former runners of liquor needed new uses for their driving skills and fast cars now that they could no longer make a profit smuggling booze.

So there you have it: some of the unintended consequences of Prohibition, and example of the way public policy can have implications for areas of social life that seem far removed from the topic at hand.