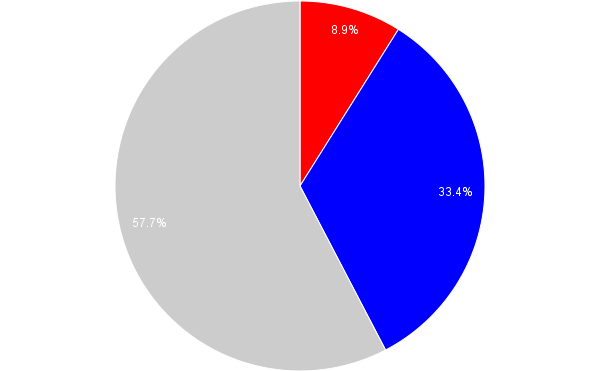

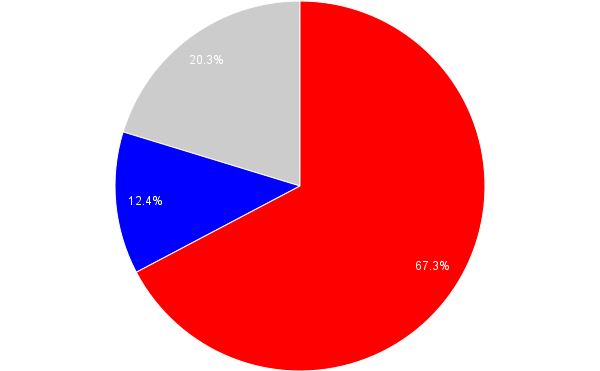

There is no one answer to the question, “How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender?” But demographer Gary Gates, who works for the Williams Institute at UCLA’s School of Law, has compiled the results from nine surveys that attempt to measure sexual orientation — five of them from the U.S. He estimates that 3.5% of the U.S. population identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual, while 0.3% are transgender. Here is the breakdown for the different surveys:

He also points out that bisexual identification is generally more common among women than among men. Among women, more than half of the lesbian/bisexual population identifies as bisexual; among men more than half identify as gay.

As is the case with race, we may rely on self-identification when it comes to sexual orientation. But criteria external to individuals’ identities may matter as well. These include the perceptions or actions of others (such as cross-burning or job discrimination), as well as qualities measurable by impersonal means (such as phenotypical traits or genes). In the case of sexual orientation more than race, these externally-measurable qualities include behavior (such as the gender of those one has sex with). The interpretation of these qualities, and their measurement, necessarily are highly contingent on social constructions.

In the case of sexual orientation, the questions are not usually asked, so the answers are not bureaucratically normalized. If the government and other data collectors were to start asking the question regularly, the results would probably settle down, as they have with race. In Michel Foucault’s terms, you might say the population is not disciplined with regard to sexual orientation as well as it is with race. (Of course, the public is unruly when it comes to measuring race as well, especially outside those outside the Black/White dichotomy, as “Asians” and “Hispanics” often offer national-origin identities when asked to describe their race.) Settling down doesn’t mean there would be no more changes, just that variability between surveys would probably decline.

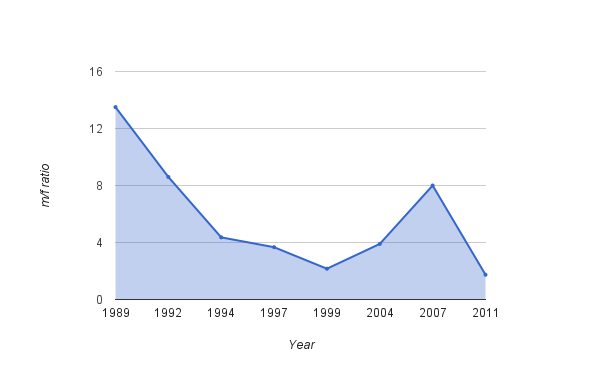

Because of this complexity, it is interesting to compare results when people are asked about their sexual behavior, and their sexual attraction. Here surveys find much higher rates of gayness. As Gates shows, for example, 11% of Americans ages 18-44 report any same-sex sexual attraction, while 8.8% report any same-sex sexual behavior.

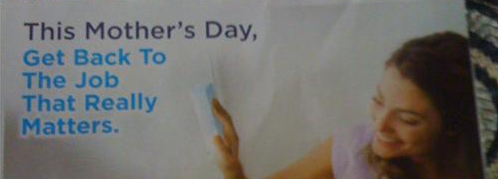

Whether demographers, or the public, or anyone else, considers these experiences and feelings to define people as gay/lesbian or bisexual is not resolved. For example, as Gates notes in a much longer law review article that describes the methods behind his report – and the reactions to it – some media simply ignored the self-identified bisexual population, and those with same-sex attraction or behavior, declaring that the gay and lesbian population was less than 2% of Americans. Others concluded that the commonness of bisexuality implies most gays and lesbians in fact have a “choice” about their sexual orientation.

I recommend the law review article for Gates’s in-depth discussion of “the closet” issue with regard to surveys, and the problem of measuring concealed identities — which vary according to social context and sometimes change over the course of people’s lives.

I’m grateful that Gates has pursued these questions, and taken a lot of grief in the process. He concludes:

These are challenging questions with no explicitly correct answers. The good news is that strong evidence suggests that, politically at least, the stakes in this discussion are no longer rooted in an urgent need to prove the very existence of LGBT people. This progress hopefully provides the space to more critically and thoughtfully assess these issues in an environment where a sense of urgency is not paramount. Today, the size of the LGBT community is less important than understanding the daily lives and struggles of this still-stigmatized population and informing crucial policy debates with facts rather than stereotype and anecdote.

As with race, measurement of sexual orientation may be essential to legal and political responses to inequality and discrimination — even as the process helps solidify fixed identity categories we might rather do without.

Philip N. Cohen is a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park, and writes the blog Family Inequality. You can follow him on Twitter or Facebook.