Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

Isabella was the second most popular name for baby girls last year. She had been number one for two years but was edged out by Sohpia. Twenty-five years ago Isabella was not in the top thousand.

How does popularity happen? Gabriel Rossman’s new book Climbing the Charts: What Radio Airplay Tells Us about the Diffusion of Innovation offers two models.* People’s decisions — what to name the baby, what songs to put on your station’s playlist (if you’re a programmer), what movie to go see, what style of pants to buy — can be affected by others in the same position. Popularity can spread seemingly on its own, affected only by the consumers themselves communicating with one another person-to-person by word of mouth. But our decisions can also be influenced by people outside those consumer networks – the corporations or people produce and promote the stuff they want us to pay attention to.

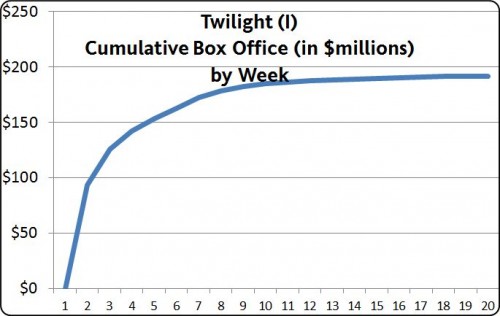

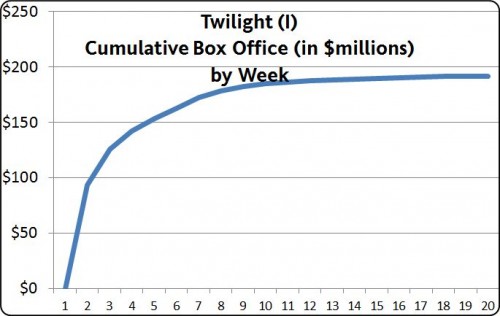

These outside “exogenous” forces tend to exert themselves suddenly, as when a movie studio releases its big movie on a specified date, often after a big advertising campaign. The film does huge business in its opening week or two but adds much smaller amounts to its total box office receipts in the following weeks. The graph of this kind of popularity is a concave curve. Here, for example, is the first “Twilight” movie.

Most movies are like that, but not all. A few build their popularity by word of mouth. The studio may do some advertising, but only after the film shows signs of having legs (“The surprise hit of the year!”). The flow of information about the film is mostly from viewer to viewer, not from the outside.

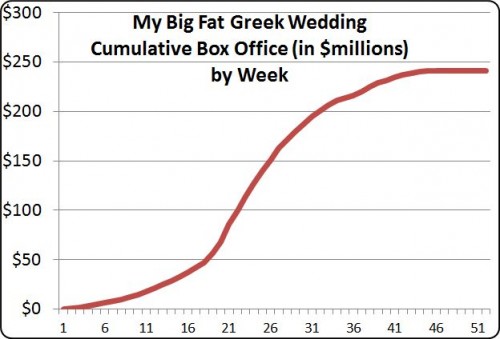

This diffusion path is “endogenous”; it branches out among the people who are making the choices. The rise in popularity starts slowly – person #1 tells a few friends, then each of those people tells a few friends. As a proportion of the entire population, each person has a relatively small number of friends. But at some point, the growth can accelerate rapidly. Suppose each person has five friends. At the first stage, only six people are involved (1 + 5); stage two adds another 25, and stage three another 125, and so on. The movie “catches on.”

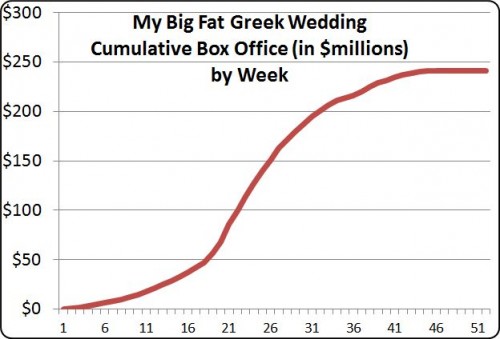

The endogenous process is like contagion, which is why the term “viral” is so appropriate for what can happen on the Internet with videos or viruses. The graph of endogenous popularity growth has a different shape, an S-curve, like this one for “My Big Fat Greek Wedding.”

By looking at the shape of a curve, tracing how rapidly an idea or behavior spreads, you can make a much better guess as to whether you’re seeing exogenous or endogenous forces. (I’ve thought that the title of Gabriel’s book might equally be Charting the Climb: What Graphs of Diffusion Tell Us About Who’s Picking the Hits.)

But what about names, names like Isabella? With consumer items – movies, songs, clothing, etc. – the manufacturers and sellers, for reasons of self-interest, try hard to exert their exogenous influence on our decisions. Nobody makes money from baby names, but even those can be subject to exogenous effects, though the outside influence is usually unintentional and brings no economic benefit. For example, from 1931 to 1933, the first name Roosevelt jumped more than 100 places in rank.

When the Census Bureau announced that the top names for 2011 were Jacob and Isabella, some people suspected the influence of an exogenous factor — “Twilight.”

I’ve made the same assumption in saying (here) that the popularity of Madison as a girl’s name — almost unknown till the mid-1980s but in the top ten for the last 15 years — has a similar cause: the movie “Splash” (an idea first suggested to me by my brother). I speculated that the teenage girls who saw the film in 1985 remembered Madison a few years later when they started having babies.

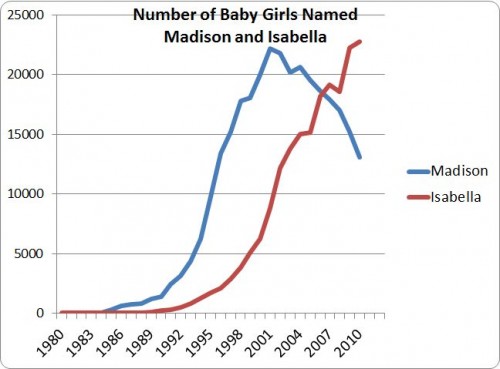

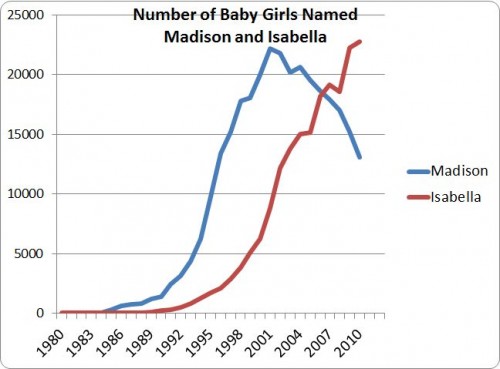

Are these estimates of movie influence correct? We can make a better guess at the impact of the movies (and, in the case of Twilight, books) by looking at the shape of the graphs for the names.

Isabella was on the rise well before Twilight, and the gradual slope of the curve certainly suggests an endogenous contagion. It’s possible that Isabella’s popularity was about to level off but then got a boost in 2005 with the first book. And it’s possible the same thing happened in 2008 with the first movie. I doubt it, but there is no way to tell.

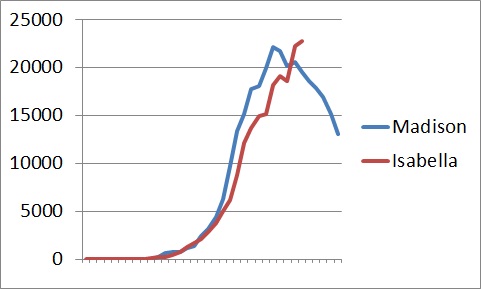

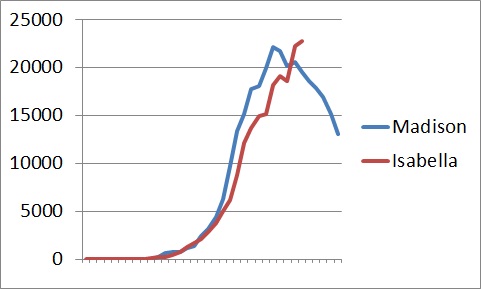

The curve for Madison seems a bit steeper, and it does begin just after “Splash,” which opened in 1984. Because of the scale of the graph, it’s hard to see the proportionately large changes in the early years. There were zero Madisons in 1983, fewer than 50 the next year, but nearly 300 in 1985. And more than double that the next year. Still, the curve is not concave. So it seems that while an exogenous force was responsible for Madison first emerging from the depths, her popularity then followed the endogenous pattern. More and more people heard the name and thought it was cool. Even so, her rise is slightly steeper than Isabella’s, as you can see in this graph with Madison moved by six years so as to match up with Isabella.

Maybe the droplets of “Splash” were touching new parents even years after the movie had left the theaters.

————————

* Gabriel posted a short version about these processes when he pinch hit for Megan McCardle at the Atlantic (here).