August 29th is the anniversary of the day that Hurricane Katrina devastated the Gulf Coast and side-swiped New Orleans, breaching the levees. These posts are from our archives:

Was Hurricane Katrina a “Natural” Disaster?

- Profits Over People: The Human Cause of the Katrina Disaster

- An Iconic Image of Government Failure: Empty, Flooded School Buses

Racism and Neglect

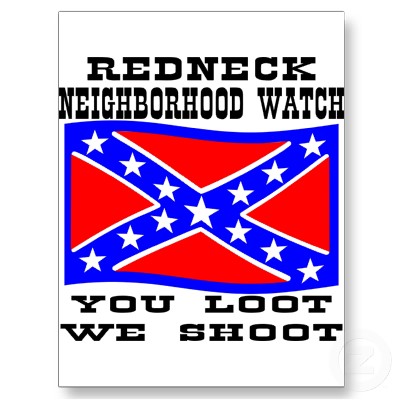

- Racial Violence in Algiers Point

- Hurricane Katrina and the Demographics of Death

- The Fate of Prisoners During Hurricane Katrina (pictured)

Disaster and Discourse

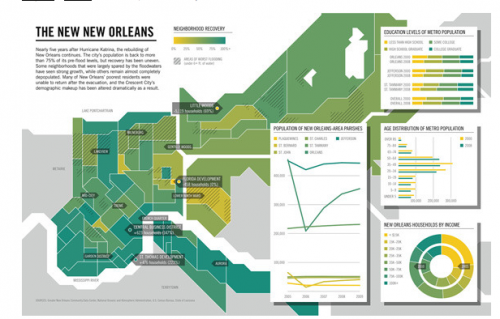

Devastation and Rebuilding

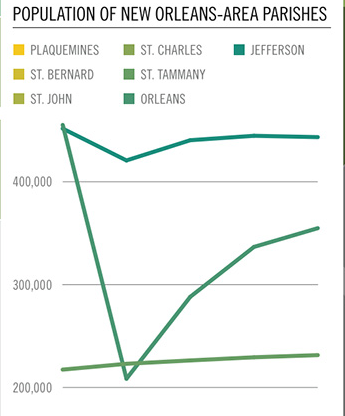

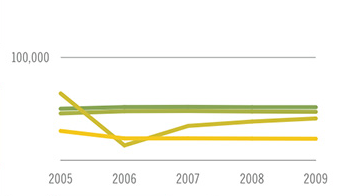

- Slow Recovery on the Gulf Coast (pre-oil spill)

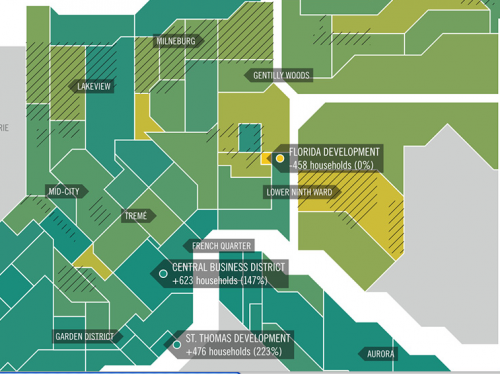

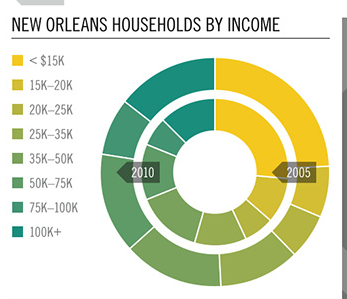

- Population Recovery in New Orleans

- Rebuilding in the Lower 9th Ward

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.