Who’s afraid of a global pandemic? We all are, at the

moment. But like so many other forms of fear, concern about medical issues is

much more acute for people in precarious and vulnerable social positions. The

privileged—particularly those who are white and upper class—can more afford not

to be preoccupied with health and medical concerns, including pandemics.

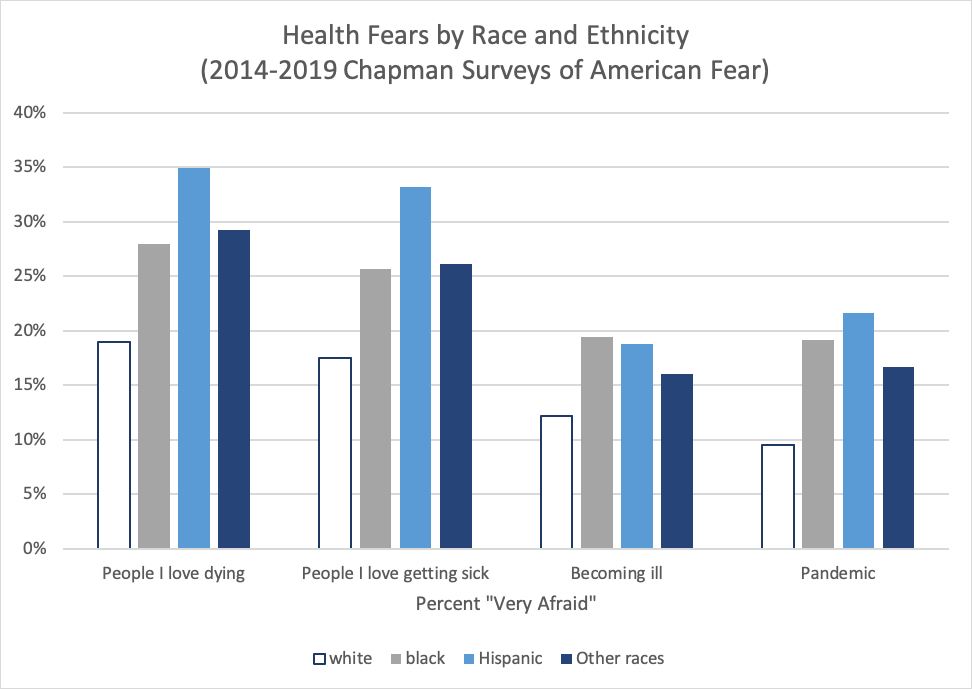

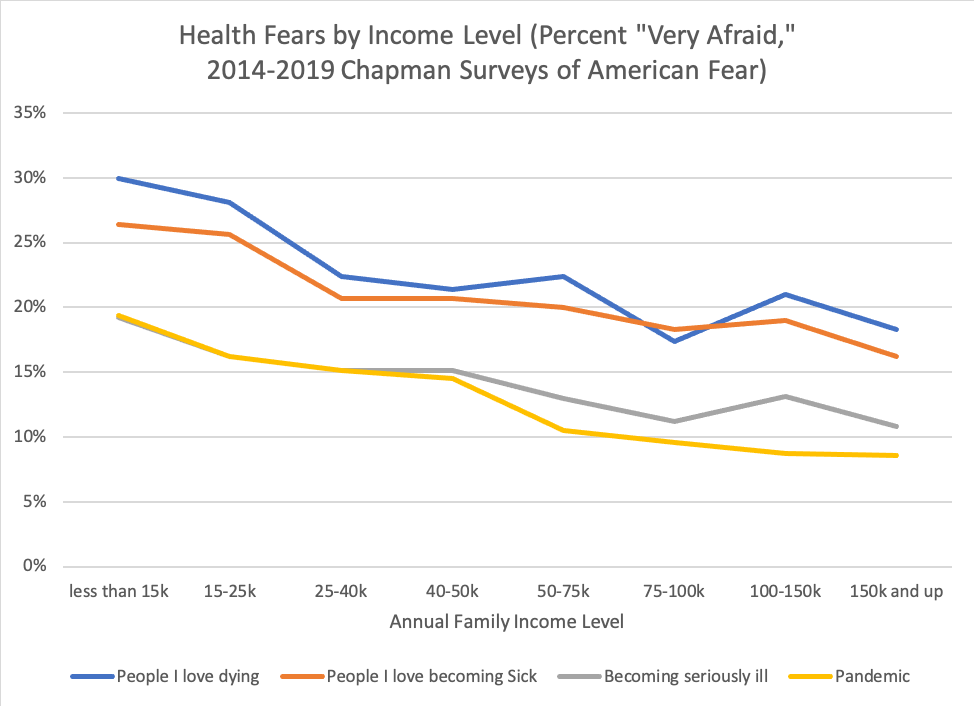

In our new book Fear Itself, we found consistent support for updating our classic theories about vulnerability. Classic theories often understand vulnerability in physical terms. But risk and vulnerability are also social, rather than primarily physical, and we found consistent evidence that members of disadvantaged status groups—particularly women, racial and ethnic minorities, and those with lower levels of social class—had higher levels of fear across many domains.

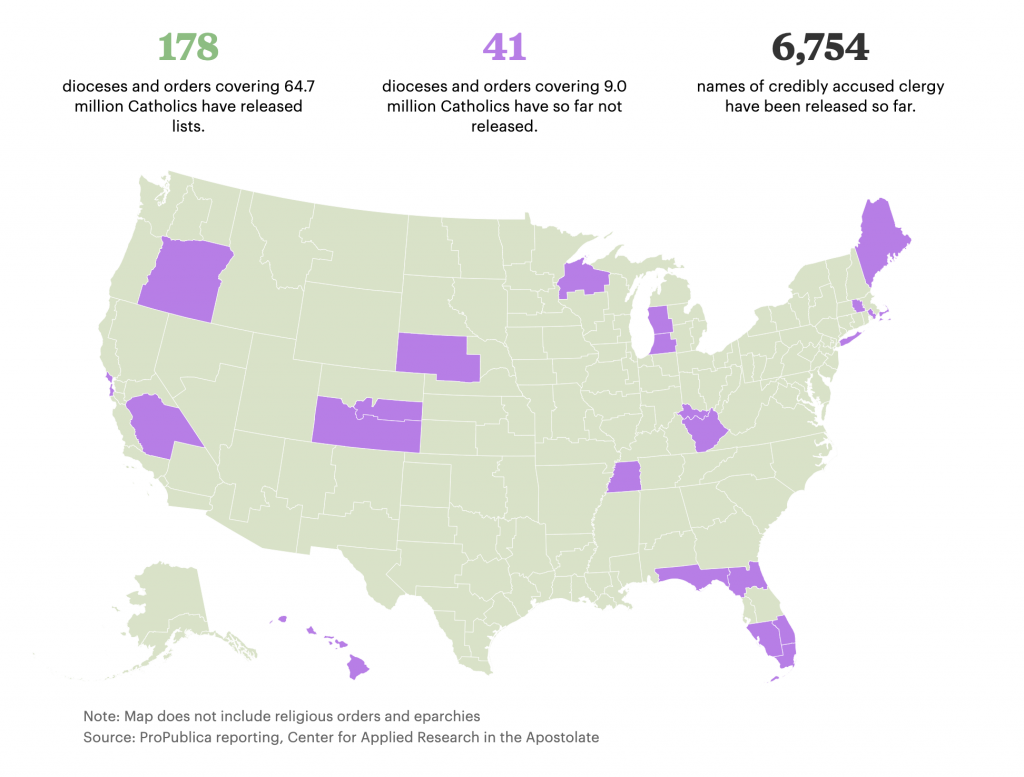

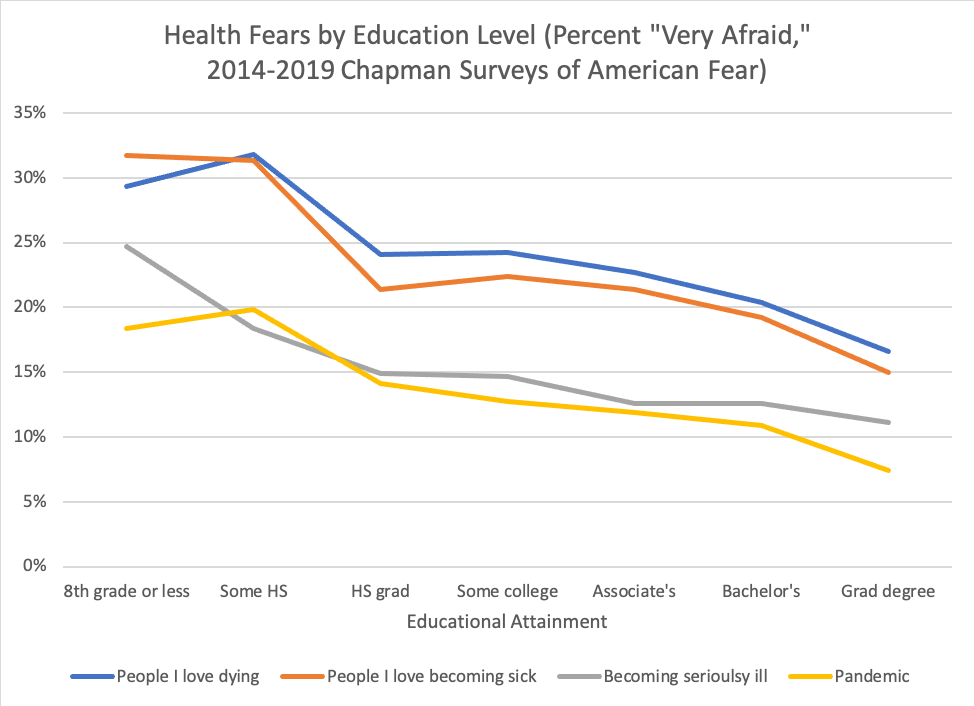

Using pooled data from six waves (2014–2019) of Chapman Survey of American Fears (CSAF), we examined the sociological patterns of fears about disease and health. We looked at fear about four specific issues: global pandemics, fears of becoming seriously ill, and fears about people you love becoming seriously ill or dying.

The racial and ethnic disparities across these four outcomes

are striking, with white Americans being significantly less likely to report

being “very afraid” of pandemics and medical issues involving themselves or

their families. Hispanic Americans reported the greatest concern about all four

issues, likely a reflection of lower rates of health care insurance and access

among Latino/a communities and individuals.

Likewise, we find clear disparities in fears about health and pandemics across different levels of education and family income. Again, the mechanisms are clear, with vast disparities in health care access in the United States, as well as the well-known social determinants of disease both playing a role.

While these patterns are not necessarily surprising, they are nonetheless disconcerting, for a number of reasons. First, in terms of the epidemiology of the Coronavirus pandemic, it is the disempowered who will disproportionately bear the brunt of the negative health effects, and who will be least equipped with the resources to adequately respond if and when they get sick. Second, when preventative public health measures such as quarantines are put in place, it is people in the working and lower classes who can least afford to take time off of work or keep their children home from school in order to comply with public health procedures.

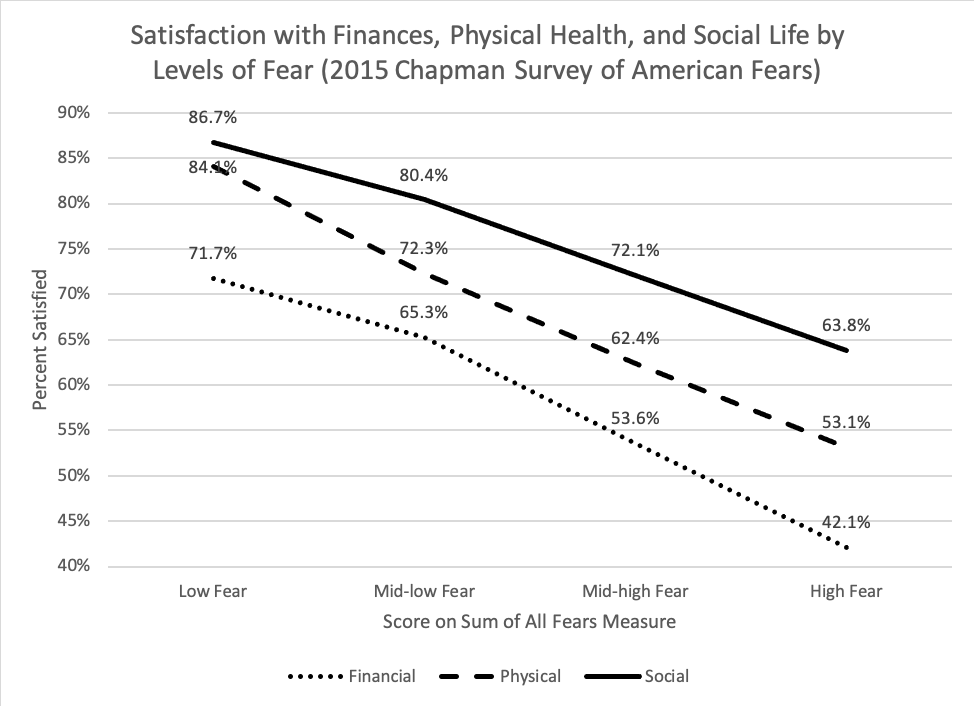

Not only does fear disproportionately prey upon people in less powerful social positions, it also exacerbates and deepens inequality. Higher levels of fear and anxiety are strongly and significantly related to harmful health outcomes, even after accounting for the social inequalities that structure who is afraid in the first place. In Fear Itself we created an omnibus fear metric we called the “Sum of All Fears” that combined levels of fear across a wide range of domains, including but not limited to health, crime, environmental degradation, and natural disasters. Scores on this global, summary fear metric once again produced strong support for social vulnerability theory; but levels of fear were also strongly connected to steep declines in quality of life across a range of domains, including social, personal, and financial well-being.

Taken together, fear is both a reflection of and a source of social inequality. This is true for the current global Coronavirus pandemic and the accompanying concerns, but it will also be the case long after the pandemic has passed. Our hope is that sociologists, social psychologists, and public health officials begin to consider how fear factors into and deepens social inequality.

Joseph O. Baker is Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at East Tennessee State University and a senior research associate for the Association of Religion Data Archives.

Ann Gordon is Associate Professor of Political Science and Director of the Ludie and David C. Henley Social Science Research Laboratory, Chapman University.

L. Edward Day is Associate Professor and Chair of the Sociology Department at Chapman University.

Christopher D. Bader is Professor of Sociology at Chapman University and affiliated with the Institute for Religion, Economics and Culture (IRES). He is Associate Director of the Association of Religion Data Archives (www.theARDA.com) and principal investigator on the Chapman University Survey of American Fears.