Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

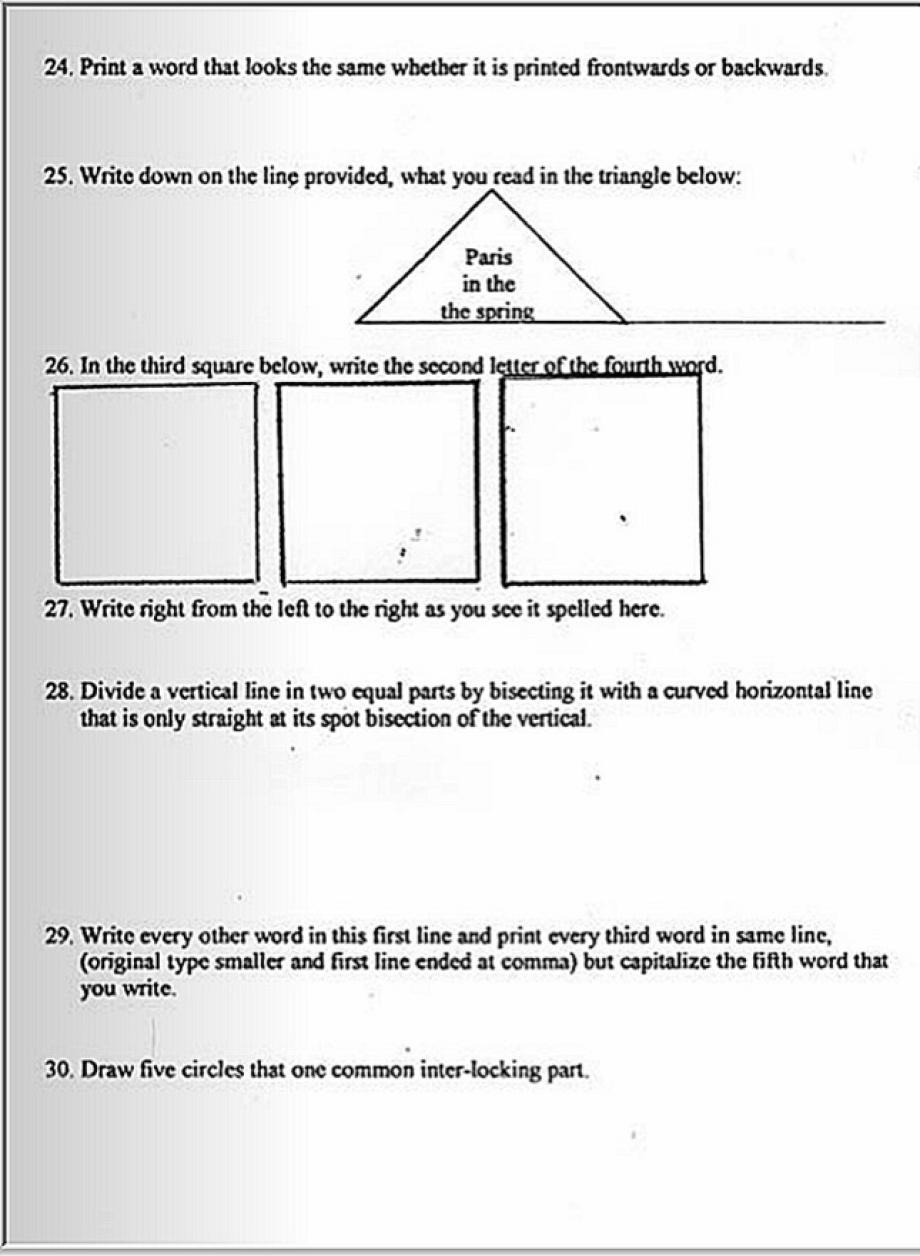

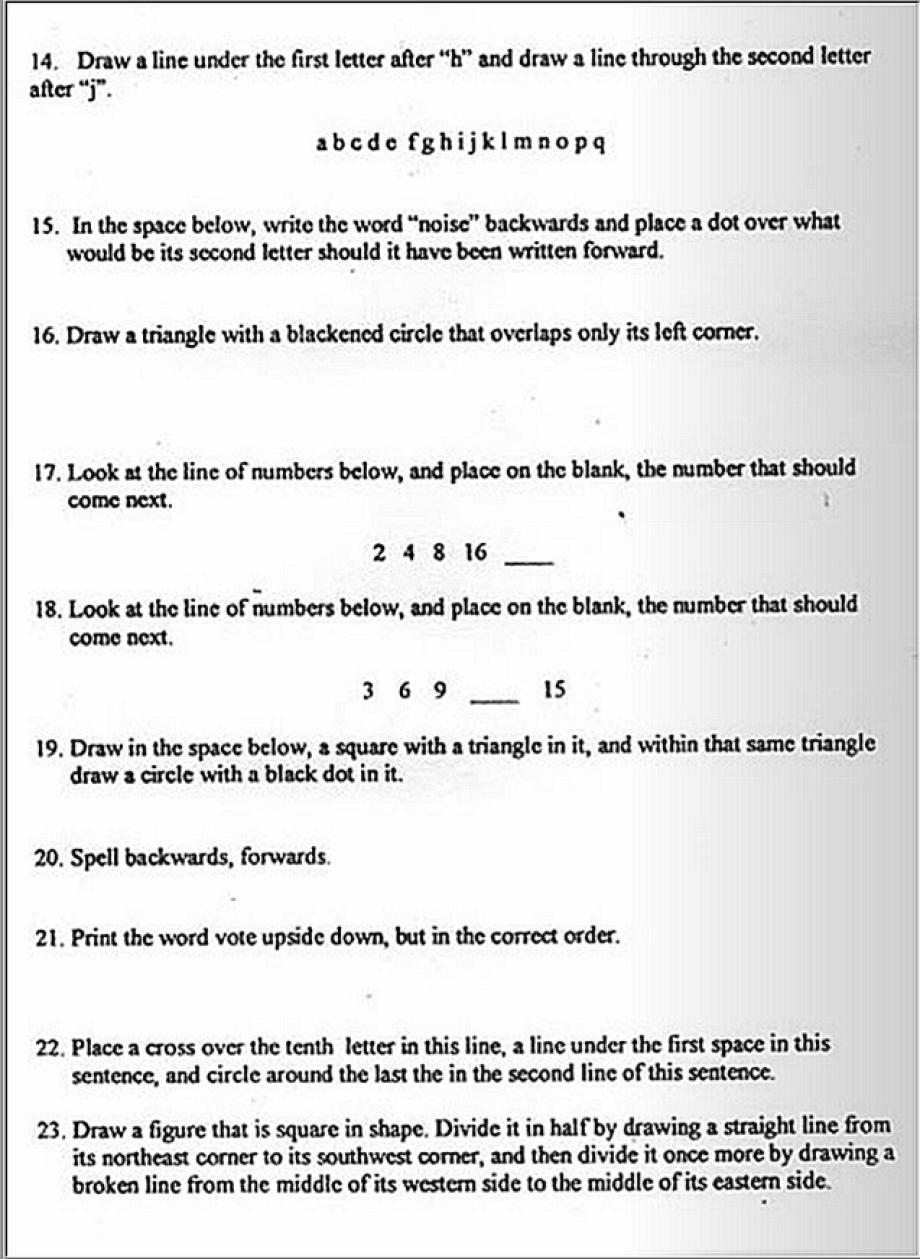

Last week the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the part of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that required states with a documenting history of discrimination to get federal approval before changing their voting laws. When the law was passed in 1965, one of its main targets were “literacy tests.”

Ostensibly designed to ensure that everyone who voted could read and write, they were actually tools with which to disenfranchise African Americans and sometimes Latinos and American Indians. Minority voters were disproportionately required to take these tests and, when they did, the election official at the polling place had 100% jurisdiction to decide which answers were correct and score the test as he liked. The point was to intimidate and turn them away from the polls. If this sounds bad, you should see the range of disturbing and terrifying things the White elite tried to keep minorities from voting.

The tactics to manipulate election outcomes by controlling who votes is still part and parcel of our electoral politics. In fact, since most voters are not “swing” voters, some would argue that “turnout” is a primary ground on which elections are fought. This is not just about mobilizing or suppressing Democrats or Republicans, it’s about mobilizing or suppressing the turnout of groups likely to vote Democrat or Republican. Since most minority groups lean Democrat, Republicans have a perverse incentive to suppress their turn out. In other words, this isn’t a partisan issue; I’d be watching Democrats closely if the tables were turned.

Indeed, states have already moved to implement changes to voting laws that had been previously identified as discriminatory and ruled unconstitutional under the Voting Act. According to the Associated Press:

After the high court announced its momentous ruling Tuesday, officials in Texas and Mississippi pledged to immediately implement laws requiring voters to show photo identification before getting a ballot. North Carolina Republicans promised they would quickly try to adopt a similar law. Florida now appears free to set its early voting hours however Gov. Rick Scott and the GOP Legislature please. And Georgia’s most populous county likely will use county commission districts that Republican state legislators drew over the objections of local Democrats.

So, yeah, it appears that Chief Justice John Roberts’ justification that “our country has changed” was pretty much proven wrong within a matter of hours or days. This is bad. It will be much more difficult to undo discriminatory laws than it was to prevent them from being implemented and, even if they are challenged and overturned, they will do damage in the meantime.

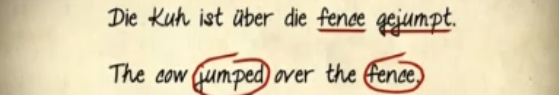

In any case, here are two examples of literacy tests given to (mostly) minority voters in Louisiana circa 1964. Pages from history (from Civil Right Movement Veterans):

Thanks to @drcompton for the tip!

Thanks to @drcompton for the tip!

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.