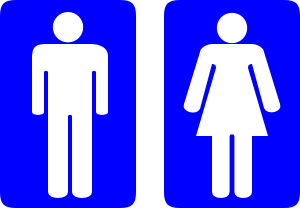

Women’s and men’s washrooms: we encounter them nearly every time we venture into public space. To many people the separation of the two, and the signs used to distinguish them, may seem innocuous and necessary. Trans people know that this is not the case, and that public battles have been waged over who is allowed to use which washroom. The segregation of public washrooms is one of the most basic ways that the male-female binary is upheld and reinforced.

As such, washroom signs are very telling of the way societies construct gender. They identify the male as the universal and the female as the variation. They express expectations of gender performance. And they conflate gender with sex.

I present here for your perusal, a typology and analysis of various washroom signs.

[Editor: After the jump because there are dozens of them… which is why Marissa’s post is so awesome…]

The Universal Male

One of the ideas that supports patriarchy is the notion that a man can be representative of all humanity, or “mankind”, while a woman could only be representative of other women. For example, in politics we see “women’s issues” segregated from everybody issues.

Washroom signs illustrate this idea by depicting the male figure simply, and the female as some kind of elaboration on the male figure. This sign expresses in words what many do with images:

The most common type of washroom sign, pictured at the top of this post, is another example. Typically, these signs depict men as people, and women as people in skirts:

In Iran, men are depicted as people, and women are people in skirts and hijabs:

Occasionally, we see that men are people, and women are people with waists:

Which highlights the absurdity of the construction of gendered bodies because, well, men have waists too.

In this sign, we see that men have torsos, and women have floating, disembodied boobs:

Women also sprout tentacles from their heads

Finally, we have a sign that, while patronizingly insulting, is interesting in that it takes the assumption of the universal male to its logical conclusion. That is, if “men” is interchangeable with “people”, and women aren’t men, then women can’t really be considered people at all, can they?

That is, if “men” is interchangeable with “people,” and women aren’t men, then women can’t really be considered people at all. But who wants to be a person when you can be a beautiful, delicate flower instead?

Opposite Sexes

There is another kind of washroom sign that, although based on the men-are-people/women-are-people-in-dresses trope, doesn’t quite fit. These signs depict men and women as triangles.

One is not an elaboration of the other. They are both simply triangles. These signs remain problematic, though, because they construct men and women as fundamentally opposite to one another. It also assumes that the viewer understands that the triangle side signifies either shoulders or a skirt, and that is not a given. Which becomes apparent when you consider this sign:

Unlike the previous signs, here the downwards pointing triangle identifies the women’s washroom, and the upwards pointing triangle signifies the men’s washroom. I assume that the angles are supposed to represent torpedo boobs and a pitched tent.

Gender, Sex, and Sexuality

In controversies over who is allowed to use which washroom, a recurring theme is the conflation of gender, sex and sexuality, as cis women insist on treating male-bodied women as some kind of threatening sexual predators. This conflation is illustrated by washroom signs themselves, which sometimes designate washrooms by gender, and sometimes by sex, sometimes accompanied by assumptions about sexuality.

Gender Performance

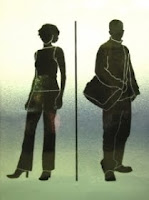

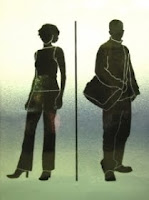

Many washroom signs do not depict the male as a universal stick figure. Instead, the distinction is made by playing up differences between how masculinity and femininity are performed. In doing so, the signs communicate essentializing notions about what makes a man or a woman. Most often, it is style of dress.

This pair of signs is interesting, because it might not immediately be apparent to the modern viewer that the individual pictured on the sign for the men’s washroom is, in fact, male. It shows that the styles we associate with masculinity are not universal across time and space.

Then we have these signs which universalize gender performance to apply it to the insect world:

Butterflies are naturally feminine because they’re pretty, and beetles are naturally masculine because they’re not pretty.

Even more suggestive of the notion that “clothing makes the man” and woman, are the signs which do not show people at all, but just gendered apparel.

Some signs incorporate gendered posture: the woman is canting, or has her eyes demurely cast downward, while the man has his feet firmly planted on the ground, displaying his physical strength.

These are also suggestive of the behaviour we expect from men and women – women should be coy and submissive; men brash and dominating.

Sex

After stick-figures, signs showing different styles of dress for men and women seem to be the most common way to designate men’s and women’s washrooms. However, like transphobic people, some signs focus on what’s under the clothes. A couple of the following photos might be mildly NSFW.

These signs are of several kinds. All are essentializing and erase trans people and people with atypical sex organs.

The first is men-have-penises/women-have-breasts. I believe that these are indicative of the degree to which breasts have been sexualized in our society as, like the sign below, they seem to be oblivious to the fact that women have genitalia, and hence construct breasts as the female equivalent of the penis.

The second group is men-have-penises/women-have-vaginas.

It seems that vaginas are shown attached to women to a far lesser extent than breasts are.

Somewhat related to the last category are the signs that pose the question: do you stand or sit when you pee?

(A note from an anonymous commenter: …the photo of the pointers/setters is from a restaurant in Philadelphia called the White Dog Cafe, where I worked for many years. There are four single bathrooms, all named after types of dogs (punny, I know) – and all explicitly non-gendered. Those bathrooms were designed in part with the West Philadelphia queer community in mind; when I worked there I had many LGBTQ coworkers, including someone who was transitioning, and it was an incredibly supportive environment. Duly noted.)

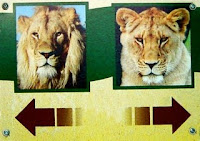

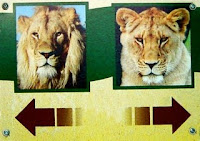

Other signs use the secondary sex characteristics of animals:

This illustrates the way we assume the universality of the gender binary, when it is not universal. For example, hens have been known to behave like roosters, and then develop male secondary sex characteristics, making the news in Sweden and China.

There was also a rooster in Italy who started to lay eggs after a fox killed all the hens.

This sign is even more essentializing, specifying the chromosome pairs you need to use the washroom:

It also universalizes the gender binary to alien races (whose legs conveniently seem to abstractly represent human sex organs) and robots.

Conflating Sex, Gender, and Sexuality

Signs can vary between designating washrooms by sex and by gender because most people assume that they are the same thing.

Her thought bubble: “shopping”; His thought bubble: “football”

This sign covers all the bases. Male as universal/female as variation: He’s a simple egg-shape, she’s wearing a dress and lipstick. Biological sex: He has a minimalist penis, she has minimalist vagina. Gender performance: He’s thinking about football, she’s thinking about shopping. It’s almost funny that the graphic designer felt that so many different elements were necessary. It’s also interesting because it illustrates how total the conflation is and the rigidity of the resulting dichotomy. Women must meet standards of femininity. Men can’t wear lipstick or enjoy shopping. And they certainly can’t have vaginas.

There’s an element of absurdity to it. We don’t segregate washrooms because people have different interests. Nor is it because of people’s wardrobe choices since, obviously, women wear pants. And, as this sign from Utilikilts points out, it’s not unheard of for men to wear skirts.

We segregate washrooms because of sex. Because of the presumed sexual interest of the opposite sex. That is, because of sexuality.

Specifically, because of male heterosexuality, which is assumed to be predatory. Heck, it’s expected and accepted as predatory, to the extent that it’s joked about.

This is unfair to a lot of men. And it becomes an excuse for those men who are predatory.

The segregation of washrooms is based on an assumption of heterosexuality, predatory in men and passive and vulnerable in women; the association of sexuality with sex, and the conflation of sex and gender. In other words, it is nonsensical. One thing we don’t segregate washrooms by is sexuality.

Uh…?

Finally, here are some signs that I just found confusing. In Germany, women are represented by fire, and men are represented by water.

Whereas in Brazil, fire represents men. Women are

represented by flowers…

This one is from Sangunburi Crater, on Jeju Island in South Korea. I’m assuming there’s an explanation for why the woman has a scuba mask on her head, and why the man is golem, but I don’t know what it is.

UPDATE: Several people responded with explanations on threads where this post has been linked. Here is one of them: The woman diver is a haenyeo, or pearl diver – there is an independent haenyo subculture that is actually pretty kick-ass and unique to Jejudo. Only the women dive. ... The golem male represents a traditional totem of men wishing the pearl-divers good luck and safety on their journeys.

From an Applebee’s in Sao Paulo. The red sign is for the women’s washroom. Obviously.

Photo Sources:

Toilet Signs

because you value your soul

Dark Roasted Blend 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

Blogoncherry

Akshay Gandhi’s Blog

Funny Photo Collection

Ahh.. Chewww!

1 Design Per Day

—————————-

Marissa has a bachelor’s degree in political science from the University of Toronto, with minors in sociology and history. She is currently finishing law school, and hopes to practice family law. She has been blogging at This Is Hysteria! for two months, where she writes about social justice issues, politics, culture and working in call centres.

Thanks to Lucy for pointing us to her fantastic post.

If you would like to write a post for Sociological Images, please see our Guidelines for Guest Bloggers.

(source)

(source) (source)

(source) (source)

(source) (source)

(source)