In an earlier post, I discussed growing trends of body modification as illustrative of the new cyborg body. Although it is debatable whether these trends are in fact “new,” (after all, various indigenous cultures have been practicing body modification long before European colonists began taking note of it in their travel diaries), I would like to continue this conversation by looking at one subculture of body modification: tattooing.

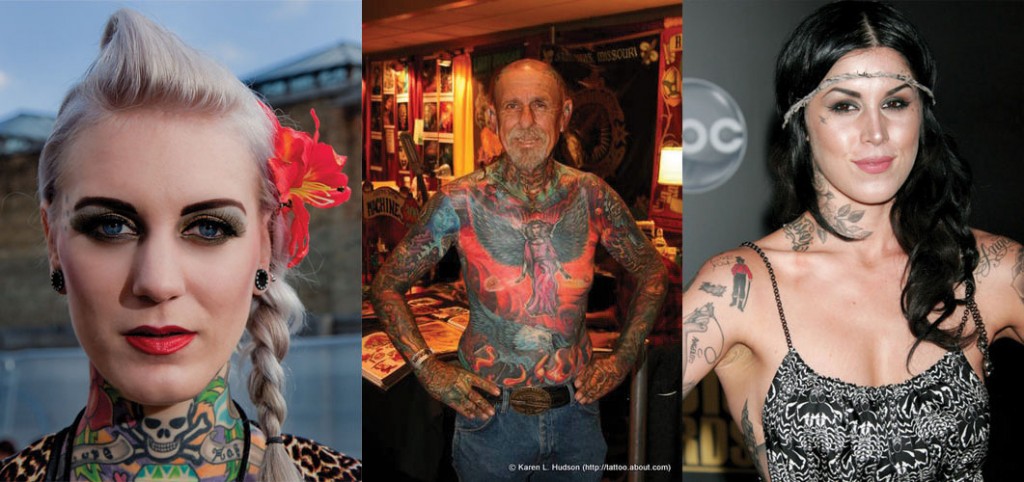

As an avid “tattoo collector” myself, I have spent the past few years attending tattoo conventions, hanging out with tattooers, and getting heavily tattooed, all while working on my research regarding the popularization of tattooing. What I notice are changing norms regarding appropriate use of the body as canvas. I would like to draw your attention to one particular trend that is growing in the tattoo subculture: facial tattoos.

What was once the purview only of convicted felons has become an increasingly normative way of expressing one’s commitment to the subculture. (For a case in point, simply Google “facial tattoos” and see what pops up.) What I notice from my interviews and discussions with tattooers and clients alike is a sharp disparity between those who see the face as a legitimate space for artistic display and those who see the face as “off limits.” Traditionally, tattooers were wary of getting tattooed on “public skin” (e.g., face, hands, and neck), as employment in the industry was unpredictable and one never knew if she would need to find another job amongst the masses. Having tattoos on public skin was almost certain to prevent employment. But things may be changing.

As the tattoo industry has become somewhat of a pop culture phenomenon, and many consumers have become visibly tattooed (full sleeves, bodysuits, and the like), tattooers have begun to see the face as a legitimate space for getting tattooed. Many of the artists I have spoken with now have prominent facial tattoos, and the ones that don’t often plan on getting them (usually something small beside one or both eyes). For many, it is now the only way to differentiate themselves from tattoo collectors or other body modification enthusiasts who now sport full body suits, stretched earlobes, and other prominent modifications. Where having full sleeves once denoted one’s status as a tattoo artist – a professional in a tightly-knit and guarded community of craftsmen – now facial tattoos serve to display one’s commitment to the profession, lifestyle, and artform. As such, facial tattoos have become a new form of (sub-)cultural capital, where those who were on the “inside” of the subculture now find themselves defending their turf from a onslaught of newcomers wanting to jump on the bandwagon.

However, even among tattooers, there is a resistance to this growing trend. Many of the traditional tattooers (those who were trained long ago or received a formal apprenticeship) that I have spent time with spoke strongly against facial tattoos. In fact, most traditional tattooers refuse to tattoo clients on public skin entirely. It is simply not a part of their habitus (to borrow Bourdeiu’s terminology). This was certainly the case for the likes of Bert Grimm, Charlie Barrs, or Amund Dietzel, traditional tattooers from the 40s, 50s, and 60s, as well as many other artists who were trained prior to the Tattoo Renaissance of the 70s. For the young man who walks into the tattoo shop and asks for his lover’s name emblazoned across his neck, he now has to find a “friend” in the industry who is willing to do it. Either that or he must risk receiving a poorly-rendered tattoo from a “scratcher” (someone untrained and unaffiliated with a tattoo shop, who purchased their equipment online) who will agree to do the piece at a dramatically reduced rate at a tattoo party or out of somebody’s basement.

However, even among tattooers, there is a resistance to this growing trend. Many of the traditional tattooers (those who were trained long ago or received a formal apprenticeship) that I have spent time with spoke strongly against facial tattoos. In fact, most traditional tattooers refuse to tattoo clients on public skin entirely. It is simply not a part of their habitus (to borrow Bourdeiu’s terminology). This was certainly the case for the likes of Bert Grimm, Charlie Barrs, or Amund Dietzel, traditional tattooers from the 40s, 50s, and 60s, as well as many other artists who were trained prior to the Tattoo Renaissance of the 70s. For the young man who walks into the tattoo shop and asks for his lover’s name emblazoned across his neck, he now has to find a “friend” in the industry who is willing to do it. Either that or he must risk receiving a poorly-rendered tattoo from a “scratcher” (someone untrained and unaffiliated with a tattoo shop, who purchased their equipment online) who will agree to do the piece at a dramatically reduced rate at a tattoo party or out of somebody’s basement.

In conclusion, as tattooing has become more popular, tattooers and those whose lives revolve around the art of tattooing must create new forms of distinction to differentiate themselves from the masses. This goes back to Bourdieu’s notion of the social field, and how forms of distinction change after the entrance of new social actors with much different forms of capital and very different habituses. Although many a Nu-Skool tattooer (those who recently joined the tattooing profession, often with art school training) sees no problem tattooing their face, hands and neck, many traditional tattooers still see it as a questionable practice and refuse to do it themselves. However, with pressure resulting from the increasing popularity of tattooing and the increasing numbers of individuals with their faces prominently tattooed, we may see an increase in traditional tattooers who choose to tattoo their face.

David Paul Strohecker is getting his PhD in Sociology at the University of Maryland. He studies cultural sociology, theory, and intersectionality. He is currently working on a larger project about the cultural history of the zombie in film. This post originally appeared at Cyberology.

For more on Bourdieu, see our posts on The Evangelical Habitus, Dumb vs. Smart Books, and The Hipster and the Authenticity of Taste.