The world’s first flight attendant was a man. He was a German named Heinrich Kubis and he was a steward on LZ-10 Schwaben zeppelin, a rigid blimp like aircraft that began ferrying passengers in 1912. Here’s Kubis at work:

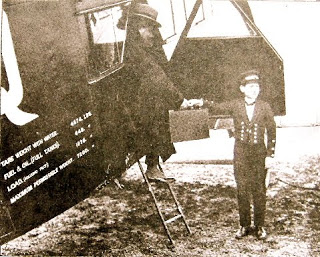

The first flight attendant to serve on an airplane was a 14-year-old boy named Jack Sanderson. It was 1922 and he was hired by The Daimler Airway (later part of British Airways):

When commercial airlines took to the sky in the U.S., it was with an all-male staff. A 19-year-old Cuban American named Amaury Sanchez was the steward for Pan American’s inaugural flight in 1928. Pan Am maintained an all-male steward workforce for 16 years.

Unnamed steward, 1920s (source):

Like Kubis’ suit and bow tie, Sanderson’s military-style jacket, and our anonymous steward’s white coat reveal, the steward role was taken very seriously: they played an important role in an elite world. This would change with the democratization of air travel and the introduction of the female flight attendant during World War II. By the ’50s, many airlines would only hire women and the occupation would become increasingly feminized and trivialized, just like the once all-male activity of cheerleading.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 10

Oliviacw — July 23, 2013

There were definitely female flight attendants before WWII. My parents had an older family friend who was a flight attendant during the 1930's - she left her job at United Airlines in order to marry a pilot in 1938. The earliest female flight attendants were often qualified nurses - the position was considered a serious role for someone who could handle emergencies.

In this analysis, it would also be worth tracing the role of the steward in relationship to other male care-taking roles - the valet, the train porter, and so forth.

wildcatforchange — July 23, 2013

There is a whole book on this that just came out (I still have yet to read it, but it is sitting on my bookshelf) called Plane Queer. From what I can tell from the intro, it seems to be a worthwhile read that provides all the details you might want. From what I can tell, it spans from early air travel through the AIDS crisis in the 1980s. I am quite looking forward to it.

[links] Link salad walks into the fire | jlake.com — July 24, 2013

[...] Before the Stewardess, the Steward: When Flight Attendants Were Men [...]

CodyK — July 24, 2013

But why did airlines change to women stewards aka stewardesses? If you visit the Boeing air museum in Seattle, there's a letter in which the idea of hiring trained nurses as stewardesses is put forward (I don't remember which airline). On the grounds that women educated as nurses would be more reliable and less "flighty" and that being able to advertise the training as a safety feature on flights would draw business. Then as now, stewardesses and flight attendants training and role emphasized safety although that may not be recognized by the general public.

Sociopress.cz » Rasa a gender v letecké historii — October 30, 2013

[…] http://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2013/07/23/before-the-stewardess-the-steward-when-flight-attend… […]

timkirkwood — May 15, 2016

Back in the 1920s and 1930s, Postmasters General Brown and Farley established the network of U.S. airways after Congress assigned them the power to consolidate air mail routes in the “best interest” of the American public. At first, only mail was flown, but gradually passenger traffic started to build. In 1922, Daimler Airways of Britain did something remarkable: It hired the world’s first airplane stewards. Undoubtedly hired because of their small stature, "cabin boys" reportedly did not serve any refreshments but offered passengers general assistance and reassurance.

“Couriers” — that’s what the first flight attendants were called in the United States. Their ranks included the young sons of the steamship, railroad, and indus- trial magnates who financed the airlines. In 1926, Stout Air Services of Detroit became the first U.S. airline to employ male aerial couriers, working on Ford Tri–Motor planes between Detroit and Grand Rapids, Michigan. Stout became part of the United Airlines conglomerate in 1929.

Then Western (1928), and Pan Am (1929) were the next U.S. carriers to employ stewards to serve food. Pan American steward Joey Carrera recalls how the crew would lug along several days worth of food because nothing edible could be found at their stopover points. In the early flying boats, the so–called galley was in the tail of the plane, and could be reached only by crawling on hands and knees through a low, narrow passageway. Re- turning to the passenger cabin while balancing food and drink took genuine skill. Stewards also worked on the ten-passenger Fokkers in the Caribbean, as gamblers traveled between Key West, Florida, and Havana, Cuba.

During the early days of commercial aviation, a pilot or first officer would often leave the cockpit to serve as a cabin attendant — helping serve the passengers in addition to helping fly the planes. But this splitting of duties proved inefficient, so airlines began to consider other options.

Boeing Air Transport (BAT), a forerunner of United Air Lines, was the first airline to hire women. Registered nurse Ellen Church convinced Steven A. Stimpson, then District Traffic Manager for BAT, to consider using women as flight attendants. BAT’s executives allowed Mr. Stimpson to conduct a three–month trial of women flight attendants, hiring Ms. Church as Chief Stewardess supervising seven other nurses. On May 15, 1930, the world’s “Original Eight” stewardesses flew for the first time.

Airline executives believed the presence of a female attendant on board would reassure passengers of the increasing safety of air travel. They thought it would be difficult for potential travelers to admit their fear of flying when young women were part of the in–flight crew. They also believed that women would cater to their predominately male passengers. They were right on target. By the end of the three–month trial, passenger bookings were steadily increasing and male passengers were arranging to fly on specific flights with their favorite stewardess. Not everyone was enthusiastic about the idea of female attendants, though. Pilots claimed they were too busy flying to have to look after “helpless” female crew members.

Flying on Boeing 80s and 80–As, stewardesses would serve their ten passengers a cold meal, usually fried chicken, apples, and sandwiches, which they would pick up at the hanger before passengers boarded the plane. On flights out of Chicago, the famous Palmer House Hotel catered the food. In 1931, Eastern Air Transport hostesses served passengers in a hanger at Richmond, Virginia. On Curtiss–Wright Condor aircraft (which had no galleys) hostesses served their 18 passengers coffee, tea, Coca–Cola, biscuits, and coffeecake from a picnic hamper. United used fine bone china until turbulence rendered that practice economically unsound. Coffee was served from thermos bottles.

In addition to a meal service, stewardesses were also responsible for winding clocks and altimeters in the cabin, swatting flies, and ensuring that the wicker passenger seats were securely bolted to the aircraft floor with the wrench they carried as part of their crew baggage. They were also required to advise passengers not to throw lighted cigars and cigarettes out aircraft windows while flying over populated areas and to make sure that passengers used the lavatory door rather than the exit door when in flight! Harriet Fry Iden, one of the “Original Eight” recalls, “Our lavatory was very nice with hot and cold water, but the toilet was a can set in a ring and a hole cut in the floor, so when one opened the toilet seat, behold, open air toilet!”

Stewardesses had to be between 5 feet, 2 inches and 5 feet, 5 inches, well–proportioned, without glasses and with good teeth. Some airlines even included calf, ankle and thigh measurements in their hiring requirements. They wore dresses, hats, gloves and high heels! At this time, stewardesses earned $110 (Eastern) to $125 (Boeing Air Transport) per month. Raises were un-heard of during the Great Depression. At the beginning of 1933, there were only 38 stewardess in the United States. Twenty–six worked for United, on Boeing aircraft; the other 12 worked for Eastern on Curtiss–Wright Condors. On May 3, 1933, American Air Ways, predecessor of American Airlines, hired its first four hostesses and a week later, hired two more registered nurses. By the time Trans–Canada Air Lines (later renamed Air Canada) was created in April 1937, the stewardess concept was firmly in place.

In the beginning, airlines preferred to hire only registered nurses, not just for their medical experience but also because it was believed that nurses’ disciplined life would transfer well to the rigors of airline travel. During World War II, the requirement was dropped because nurses were needed in the war effort, and the airlines hired only men to work on the Civil Reserve Air Fleet (CRAF) flights, which opened the job market for women on non–military commercial flights.

The stewardess career gradually evolved from something a woman performed for an average of two years before she married — into a long–term career for women and men until retirement age. This has largely been a result of better wage and benefits packages secured by unions on behalf of various flight attendant work forces. In the “old days,” stewardesses were required to quit when they got married or became pregnant.

Airlines initially hired only young women as flight attendants. Some airlines preferred that they retire or transfer to a ground job by their mid–30s! These unjustifiable policies were rendered illegal by the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Equal Employment Opportunity Commission guidelines, and numerous discrimination lawsuits. Today, airlines cannot refuse to hire somebody due to race, religion, national origin, age, disability unrelated to performing a specific job, marital status, or gender. As more men entered the profession, the job title changed from “stewardess or steward” to the current moniker of “flight attendant.” While some countries continue to use the job titles “steward and stewardess” or even “host and hostess,” the trend is to use the gender–free “flight attendant” or “cabin crew” sobriquets. Today the average age of flight attendants ranges from the late 30s to mid– 50s. Average seniority is ten years with a very low attrition rate. About half are married, while the rest include singles, divorcees, surviving spouses, parents, and even grandparents!

Before Airline Deregulation in 1978, the Government set airfares. All airlines charged the same ticket price to the same destination. So, if three different airlines flew the New York to Los Angeles route, the ticket price was the same on all three carriers. To entice you to choose themselves over the others, airlines offered amenities. Consequently, food service was much better than exists today, with steak a regular entrée on the menu. In–flight movies, music, and even a piano bar on jumbo jets were offered to attract your business. During this period, flight attendants were considered part of the package as well. Airlines chose young, slender and pretty women, and then dressed them in mini–skirts or hot pants. Airline advertising promoted this sexuality with slogans such as “We really move our tail for you,” or “I’m Sally...fly me!”

The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 took the power to set fares away from the government, and gave it to the airlines themselves, opening the door to increased competition and corporate greed. The fare wars that followed led airlines to reduce or abandon many amenities. Gone were the elaborate food services and piano bar. Flight attendant staffing was also reduced on each flight while passenger seats were added.

To save additional money, airlines attempted to roll salaries back to 1970 levels. Bargaining power was weakened, and over half the airlines that existed before Deregulation went bankrupt, merged, or were forced out of business. None of the many new start–up airlines that grew out of Deregulation are still in business today. Most have been gobbled up in airline mergers.

Source:

The Flight Attendant Career Guide- by Tim Kirkwood

I’m One of the World’s Top Male Synchronized Swimmers - MEL Magazine — December 18, 2018

[…] That’s particularly ironic given that some believe the sport was invented by Benjamin Franklin, and 19th century synchronized swimming competitions in Berlin and London were solely for men who did water dances surrounded by garlands and lanterns. They soon learned, though, that women are far more buoyant, particularly in the legs, and the sport evolved into a predominantly female pursuit. In the U.S., men were allowed to participate with women until 1941, when the governing body required they compete separately. This resulted in the aquatic version of “male flight” — when men leave certain domains once women successfully integrate into them (and which happened in cheerleading and flight attending). […]

La moda y los uniformes de las azafatas - Cultura Hoy — April 7, 2023

[…] las azafatas son en su mayoría mujeres la primera persona que ejerció la profesión de asistente de vuelo fue un hombre. Heinrich Kubis atendió a los pasajeros en el dirigible alemán LZ10 Schwaben en el año 1911. A […]

Gene Micheli — October 10, 2024

very interesting facts & knowledge. My wife of 54 years was a TWA Flight attendant for only 6 yeras until we had a family. Things have truly turned against the normal rules of weight & attractiveness in figures over the years. We have flown several times and found that flight attendants are over weight men & women and with tattoos showing. Not suitable in my day. I always enjoyed them finally as time went one, I married one and have been very happy for 55 years so far.