On this last day of Black History Month, let us return to posts past.

We have been urged to celebrate Black History Month…

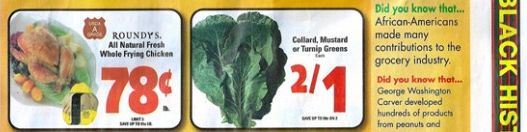

- …with fried chicken and collard greens.

- No really, with fried chicken and collard greens! (pictured)

- …by relaxing our hair.

- …with a “Compton Cookout” complete with blackface and nooses!

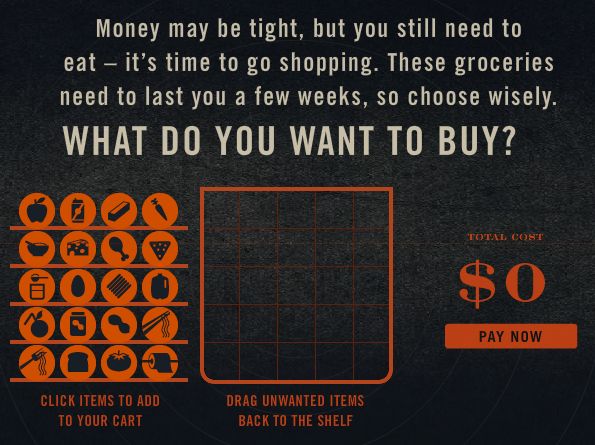

- …by buying stuff from companies that do nothing but acknowledge Black History Month.

<sarcasm> Good times. </sarcasm>

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.