In this episode, we talk with Alejandro Baer, Associate Professor of Sociology and Director of the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at the University of Minnesota.

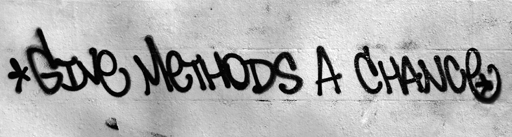

In this study, Alejandro and his colleagues sought to understand the specific discourse around anti-semitic sentiments amongst different cultural groups in Spain. To study this difficult to measure construct, the researchers created homogenous discussion groups of 7 to 9 people, led by a trained moderator. Participants were of similar demographics, leading to a ‘group discourse mode’ that revealed the structures of meaning different groups use to discuss their views on minority groups.

“When you design your groups, they have to be internally homogenous and externally heterogeneous. All of the individuals of one group share certain similarities in terms of age, political orientation, or of religious origin. You cannot put together left wing activists with conservative religious individuals of a totally different age. That’s not the idea. We want to capture the discourse they will share, not what makes them different.

– Alejandro Baer –

Podcast: Play in new window | Download