In this episode we are joined by Matthew Hughey. Matthew is an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Connecticut. He is the author of number books including the White Savior Film: Content, Critics and Consumption, The Wrongs of the Right: Language, Race, and the Republican Party in the Age of Obama, and White Bound: Nationalists, Antiracists, and the Shared Meanings of Race. Matt joins us to discuss his multi-methods approach to studying film, film criticism, and film consumption.

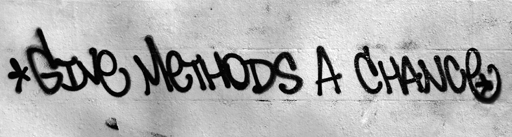

“I’m a methodologically promiscuous sociologist, so I dabble with different methodologies depending what types of questions I ask. So for example, If I wanted to know something about the ways that audience members develop, nurture, and deconstruct—in their everyday lived experiences—a film genre such as this, it would call for a kind of ethnographic strategy in which I would need to embed myself with a community of avid film goers. That type of immersion would be necessary to gain a sociologically informed view of what really figure out the relationship between people lived experiences and their cinematic evaluations. But since I was interested in a different question—notably, what kinds of demographic and interactive setting influenced how audiences make meaning of just a handful of these films, then interviews and comparisons between focus groups fit the bill for my question.”

– Matthew W. Hughey –

Podcast: Play in new window | Download