/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-qformat:yes;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:10.0pt;

font-family:”Calibri”,”sans-serif”;}

My daughter turned eleven this week. Though I agree with Allison Kimmich’s earlier post, which argued that it’s great to be a girl here in 2010, I can’t help but worry that growing up female in our culture still results in growing down.

Some examples to ponder:

When my daughter and I went to the mall to have her ears pierced last Saturday, we were deluged with anorexic size mannequins in thongs and barely-there bras.

Later, at the movies, we watched yet another film with a male protagonist (which included a male sidekick who ogled females throughout the entire movie).

For school, she worked on yet another dead white male report.

On television, she is still inundated by stories that focus on a girls looks and emphasize romance and/or beauty as the most important pursuits for a girl.

In music, there are undoubtedly many power-house female musicians, but this seems dampened by all the singing of ‘ho’s’ and ‘get-lows.’

Yet, there are positive aspects to each of these observations. At the mall, my daughter noticed the sexualization of the mannequins and complained about it, showing her awareness that our culture objectifies women in damaging ways (and revealing what I like to think is more feminist awareness in the culture generally). As for the film we watched, it did include one rockin’ strong girl character – only one, but one is better than none. As for books, we are able to find many feminist-friendly reads to fill her endless reading desires (and she subscribes to New Moon, a great feminist magazine for girls). Television may be the area most difficult to put a positive spin on, but at least there are more girl-driven shows. As for school, in general I think there is more emphasis on a diversified curriculum, one that offers more than the hetero white male view of the world.

However, I wish we had come further since I turned eleven back in 1982. The Equal Rights Amendment failed to pass that year, and has yet to be ratified. Laura Ingalls was still rocking the prairie feminism in “”Little House on the Prairie,” and my mom watched a show driven by the super-heroines “Cagney and Lacey.” Sure, Daisy wasn’t wearing much in “Dukes of Hazzard” and Suzanne Sommers was the stereotypical blonde ditz “Three’s Company,” but at least we had the strong mom and daughter trio of “One Day at a Time.” In music, female power abounded via the likes of the GoGos, Joan Jett, and Stevie Nicks. And ET, the top grossing film of the year, gave us one of my longtime favorite female actresses, Drew Barrymore. It was the year Women’s History Week was officially recognized, which has happily expanded to an entire month. (Ah, would that we could have inclusive history year round!)

In my hazy recollections of being eleven in 1982, I recall feeling I could be or do anything I set my sites on. I think here, in 2010, my daughter feels the same despite the fact popular culture still inundates her with the message she is only a sex object, only good for how she can please men, only important so long as she “plays by the rules” and shrinks to fit the mold of the “ideal female.”

As her world expands to include more ideas and experiences, her body is still expected to shrink to fit ever smaller and tighter fashions. As she grows up, the “queen be” culture at school seems to become ever meaner and more judgmental. As she is able to watch “more grown up” television and films, she is introduced incessant sexualization, dehumanization, and silencing of females. And, as her body starts to show the markers of womanhood, she will undoubtedly become more battered by the male gaze of a culture that is more pornified than ever.

Alas, growing up for girls in our culture in many ways still means growing down – but with feminist moms like ourselves guiding our daughters as they grow, I take heart in the fact that many girls are given the opportunity to expand their thinking, their horizons (and yes, even their bodies) without exhortations to “be quiet and diet.”

Last Monday, I closed on the first apartment I have ever owned. It took a year to sell. We had to move to a rental to make room for the twins before it sold. It drained my savings. It is a huge relief.

Last Monday, I closed on the first apartment I have ever owned. It took a year to sell. We had to move to a rental to make room for the twins before it sold. It drained my savings. It is a huge relief. This week there’s a heated thread running through the

This week there’s a heated thread running through the

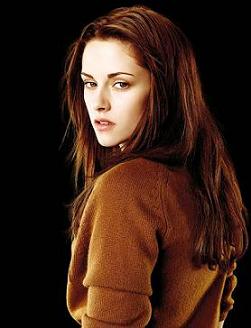

The Mommy Myth That Will Not Die: Bella Swan and Global Motherhood

The Mommy Myth That Will Not Die: Bella Swan and Global Motherhood I’m a day late in posting this month’s Mama w/Pen column because, well, this mama has gone back to work. With huge passion for

I’m a day late in posting this month’s Mama w/Pen column because, well, this mama has gone back to work. With huge passion for