Molly MacDermot is the Director of Special Initiatives at Girls Write Now

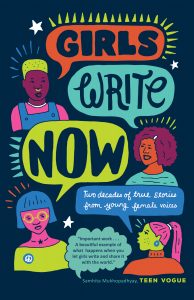

I’ve had the honor of editing five annual-anthologies for Girls Write Now. Today’s next generation of women writers are alright, and their stories are making the world better. They’re also making me feel better —filling me with hope. When Tin House editor Masie Cochran proposed publishing an anthology that showcases two decades of true stories from our young female writers, I was ecstatic. Finally, readers can enjoy the evolution of female thought in one book. Pre-order your copy from Books Are Magic, here.

I’ve had the honor of editing five annual-anthologies for Girls Write Now. Today’s next generation of women writers are alright, and their stories are making the world better. They’re also making me feel better —filling me with hope. When Tin House editor Masie Cochran proposed publishing an anthology that showcases two decades of true stories from our young female writers, I was ecstatic. Finally, readers can enjoy the evolution of female thought in one book. Pre-order your copy from Books Are Magic, here.

In Girls Write Now: Two Decades of True Stories from Young Female Voices (Tin House/October 17, 2018), you’ll meet Danni Green (her knockout essay “Dear Kanye” opens the collection), who can’t get her dad to sign her financial aid paperwork for college. She desperately wants to believe she’s meant for a different life than what she sees around her, but she’s not sure if believing is enough. You’ll witness Romaissaa Benzizoune wrestle with wearing a hijab to school, and Maggie Wang’s struggle to be what she calls “a model minority girl.” You’ll also delight in the lighter moments, like Tashi Sangmo remembering the morning bird chatter in her birthplace of Tibet, or Michaela Burns peeling red apples with her grandmother.

Together, these stories offer an overdue portrait of what it is to be a girl in New York City, and in America as a whole. They’re stories we desperately need to hear. 100% of these writers are high-need. 94% are girls of color. Many are first- and second-generation immigrants. Astonishingly, 100% of them have gone on to college and the majority have graduated, flying in the face of national averages (nationwide, only 8% of low-income students will matriculate). And trust me, we’ll be seeing many of these names on book covers for years to come.

An excerpt from Danni Green’s “Dear Kanye”. Danni was born in New York and graduated from Lewis and Clark in Portland, Oregon

Dear Kanye, January 14, 2012 7:45 pm

Nine days ago I called financial offices of the colleges I applied to. Told them I had to submit my FAFSA without parental information. Told them Shawn won’t give me his information and my mother and I have tried. Told them how Shawn raises his voice, shows his ignorance, and shouts like he’s Otis Day. How he calls me stupid. Says I shouldn’t be trying to get money from the government. Every time my mom and I try.

Each college said my parents are married and Shawn lives in the house so they couldn’t help me. They told me I was in a tough situation. They told me I was in a tough situation like I didn’t know that. Like I don’t see the lives of the people I live with and how content like a snake has opened its mouth and swallowed their lives whole. My brother Robert is jobless. Almost thirty. Has an Associate’s degree and no idea what to do with his life. My sister Jessica is sleeping with the man she loves and isn’t her husband. She just got laid off. Has four children and no more Food Stamps. And her rent has to be paid. My brother Darius made a house out of my Grandfather’s room to avoid everything that’s on the outside of his door. My younger brother Philip has taken the Geometry Regents three times. Cuts classes. Smokes weed and wonders what he’ll do with his life. My mother. Had she gone to UCLA would be a doctor right now. The closest Aunt Carla has gotten to being an actress is watching the Academy Awards every year. She flips the pages of her celebrity tabloids looking for herself.

Who am I supposed to look up to? Who is supposed to show me how I can make my dreams real?

I’m watching Jon Sands and Adam Falkner live at The Bowery Poetry Club. But I’m sitting in my computer chair looking at them on a screen. Seeing them makes me want to pull the pretty stars out the sky. Rip open my chest and stuff them in. Because I want to be pretty. On the inside. And I’m hoping stolen stars can shine away whatever’s in me trying to kill the person I can be if I were only not Here.

Adam was my English teacher. Last summer I bought Jon Sands’ book. I know this guy. Like had conversations with this guy. Like went to this guy’s workshops. If they are not made of better stuff than me like stars then why are they where I want to be and I am not?

I’m not in a tough situation, Kanye. But if I don’t get out of the house on Wyckoff Street I will be, but it’ll be My Life. It’ll be a husband I don’t love, an affair to make me feel alive, a checking account with a zero balance, a job that’ll brand me Good Enough and children whose faces ask, What’s for dinner?

Currently it’s 7:54. The 14th day of 2012. A Saturday. But it feels like 2011 and 2010 and ’09 and ’08 and ’07 and ’06 and every year when I felt I was absolved of any good thing in me the second I walked through the front door of my house. Barriers between the days are crumbling and morphing 24 hours into one long minute.

There is too much contempt in my soul to have a life like the ones I see daily. My family has redefined happiness to make their life mean something. Since the second semester of tenth grade I worked my ass off to get A’s. I lost sleep to write essays, didn’t hang out with friends to do homework.

But it’s slowly sinking in. There isn’t an escape from what dirties the dishes and puts the dust between the floorboards of my house. Not living your dreams is a sickness. My parents are carriers. It is in my plasma waiting to infect my cells. And sometimes I cry like I’m terminally ill. The tears tumbling down to my shirt is evidence that I’m dying. Because everything has just gotten so hard. Like breathing. Like having faith in myself. Like believing I won’t stay Here. College was supposed to get me out of Here.

Now I’m too full of fear that I’m going to be My Family. I’ve seen the way their muscles fold, how their joints crack. I feel that what’s in Them is seeping into me. At times I ask myself Who am I kidding thinking that I’ll be different? That I’ll do something with my life? Adam is playing the piano. Jon Sands just read a poem. I like it. The crowd clapped. I want someone to clap for me. To be proud of me. Tell me Good Job. So I could stop thinking I’m such a failure. Because I strived for college but can’t pay and will likely defer a year and I’ll see my friends leave and I will stay. Jon Sands is up in front of people. A mic before him. Performing poems. All I want to do is write poems. Touch someone with my poems. I want someone to like them. What am I doing with my life that I’m not on stage. That I’m not There? If I were There I wouldn’t know another hungry night, I wouldn’t be scared to pray. I wouldn’t wake up feeling so weak. I’d be doing something with my life. I’d…I’d… Did you ever ask yourself, Kanye, what am I doing with my life that I’m not There? If you did. What was your answer?

Roxane Gay’s advice to young women writers:

“Everyone has a voice. It’s just a question of just finding the courage to use it, and the first step in finding the courage is knowing that no matter who you are or how quiet you think your voice is, your voice matters. You’re never going to please everyone with what you say, but you don’t have to worry about that. You have to only satisfy yourself to start with, and I think, with that kind of acceptance, you can begin to use your voice. Regardless of any insecurities you feel have to have an innate confidence in yourself and your voice because if you don’t believe in your voice, then no one else is going to listen.”

—Roxane Gay

Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society invites submissions for a special issue titled

Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society invites submissions for a special issue titled

This here post comes straight from dear friend of GWP and mine, and fellow writer,

This here post comes straight from dear friend of GWP and mine, and fellow writer,