As someone immersed in the process of writing a graphic memoir, and a serious newbie, imagine my delight when I came upon the Ladydrawers Comics Collective. Imagine my further delight when I learned that this collective is based in my new hometown, Chicago. I waited all of three seconds before reaching out to learn more. The result is the interview below, with three of the collective’s members who were gracious enough to answer my (myriad) questions.

As someone immersed in the process of writing a graphic memoir, and a serious newbie, imagine my delight when I came upon the Ladydrawers Comics Collective. Imagine my further delight when I learned that this collective is based in my new hometown, Chicago. I waited all of three seconds before reaching out to learn more. The result is the interview below, with three of the collective’s members who were gracious enough to answer my (myriad) questions.

Anne Elizabeth Moore is a Fulbright scholar, a UN Press Fellow, the Truthout columnist behind Ladydrawers: Gender and Comics in the US, and the author of several award-winning books including Cambodian Grrrl (Cantankerous Titles 2011), Unmarketable (The New Press 2007), and New Girl Law. Fran Syass is a filmmaker and artist from Chicago and recently graduated The School of the Art Institute. Lindsey Smith is an undergraduate student at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and currently pursuing a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree with a focus in Animation and Film.

Here, they talk to me about hybridity, intersectionality, love affairs with comics, gender and racial bias in the comic-book world, their new documentary film, breaking even, and what Jane Addams has to do with it all.

Enjoy! – Deborah

GWP: Anne, you founded the Ladydrawers Comics Collective after a decade in the comics industry and were recently called “one of the sharpest thinkers and cultural critics bouncing around the globe today” by Razorcake. I understand the collective began in 2010 as a class you taught at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, with volunteers from outside of academia and professional cartoonists coming in to talk to the students. Three years later, what’s your vision for the collective now?

GWP: Anne, you founded the Ladydrawers Comics Collective after a decade in the comics industry and were recently called “one of the sharpest thinkers and cultural critics bouncing around the globe today” by Razorcake. I understand the collective began in 2010 as a class you taught at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, with volunteers from outside of academia and professional cartoonists coming in to talk to the students. Three years later, what’s your vision for the collective now?

ANNE ELIZABETH MOORE: Well, the research we use began a decade ago, and I did start teaching a class in 2010, but folks didn’t really cohere as a collective until the summer of 2011. It’s hard, as a collective member, to really have a vision for what a bunch of people will want to do for even five minutes down the line, much less six months, and our structure is pretty loose. So I’ll ask Francis to weigh in on this too. He was in that class, and is the visionary behind Comics Undressed, the documentary, so pretty heavily involved in decision-making about what we’ll be doing in the coming months. But I can tell you what we’ve committed to, besides the documentary we’re hoping to fund. In February we’ll have an exhibition in an art space in Pilsen that showcases political-themed work. And then for the next year we’ve developed a pretty amazing program for the Truthout comics I do monthly: I’ll be tracking global gendered labor issues through the production line of fast fashion and the sex trade, starting with retail workers in the US and going back through warehouses and factories—particularly in Cambodia, which I’ve written about for years. There the garment trade also raises a lot of questions about the sex industry and the really under-examined anti-human trafficking industry, which is often based on fear of sex and women’s economic power and not on facts at all. Those strips will start to appear in August, and while the first two years of the Truthout series brought in a different artist each month, these will work with an artist over a period of three months, so we can develop a better language and narrative—so it’s more evident how these things all interconnect.

Truthout’s been incredibly supportive of our work in investigative comics journalism and innovative research methodologies. We’re really excited to continue working with them.

GWP: I love Truthout, another Chicago-based gem. Next question. I’ve become intrigued with the way academic theory is increasingly, and literally, informing comics—Winnicott running through Alison Bechdel’s Are You My Mother? seems to be just one example. Women’s eNews described Ladydrawers’ work as “Making an art form out of researching and publishing findings that others might write or talk about.” What kinds of theories and research findings interest you most these days, and what makes comics an apt vehicle for knowledge dissemination?

ANNE ELIZABETH MOORE: Comics have always, always, always been a hybrid form as open to influence from the literary or academic worlds as from the pop cultural worlds. Their very hybridity makes them a good way to explore difficult ideas. But this project started as a way to look at and research first gender, and then racial bias in the comic-book world. We were never going to use a standard research paper format to present that work—that just doesn’t make sense. Still, ranking comics on a scale established by literature does the form an injustice. Comics are a visual medium. Literature isn’t. We can’t overlook that.

GWP: Speaking of overlooked, you’ve noted, Anne, that when you were editing Best American Comics (the annual anthology published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), there was no shortage of submissions by women, but that traditionally barriers to inclusion and visibility carry a gendered tinge. What are the continued barriers, would you say?

ANNE ELIZABETH MOORE: Well the first year and a half of the Truthout strips looked at the phenomenon of gender bias—and to a lesser degree, race and class bias—within comics really closely, and proved it, and provided some potential for changing it. Then more recently the last six months of Truthout strips lay out the broader cultural implications pretty clearly: there’s a historic lack of protection for women as a labor force, and a legal structure within cultural production that fails to acknowledge feminine forms or female-identified producers, which isn’t even an issue just for women, we see when we start to look at trans* identities—it’s an issue of gender policing being hidden within otherwise seemingly innocuous bodies of law like intellectual property rights. So what we end up with, which we shorthand to “misogyny” and “transphobia” when we talk about gender, and then “white supremacy” when we see the same system applied to folks with a diversity of racial identifications, isn’t actually a single, identifiable flaw within an overall system. It is endemic to the entirety of the system. The barriers are that capitalism is designed to work best for straight white men, and single-issue organizing to change it—most feminist concerns, for example—merely enfolds a new group of folks into this category of inclusion, although often for only a short time. Only an intersectional approach—that considers race and economics and physical ability and a range of gender identities—will offer possibilities for improvement, but the real, lasting barrier is getting folks who feel hurt by the system from their particular vantage point to see that.

GWP: You describe the collective as “a curiosity-driven, open-ended, exploratory body of friendly amateur researchers, concerned with who gets to say what in our culture and how they may or may not be supported in or compensated for saying it.” Any plans to collectively monetize the important work that you all do?

ANNE ELIZABETH MOORE: Interestingly, this is a project largely about, and situated within, capitalism: the “profit” to folks who work with us, while in school, are educational, and then once folks graduate, we try to make sure folks get paid or somehow compensated for their labor. But we’re also open to everyone, and part of the deal in working with us is knowing that we’ll do our best to get you something for your labor. Because comics are labor unlike any others in cultural production: it’s grueling, even compared to film, and no economy has really cohered around it for all participants. We try not to work with folks who are too ego-driven—folks who will take more than a share of the pie, whether the emotional one or the economic one—but it’s all pretty loose. Stuff happens. But the point is: establishing an economic base for underrepresented creators is important, to shift the dynamics of the industry. But to me, getting rich from doing that isn’t.

FRAN SYASS: Monetary success seems somewhat irrelevant to the Ladydrawers ethos, and I can’t find there is much profit for what we do. Though many of us are looking for our big breaks one day, this group isn’t really about that. As long as we get our research across and as long as we’re content with the work we do than, we’re just happy to break even by the end of the day.

GWP: You’re in Chicago. Erin Polgreen launched Symbolia from out here too. My partner and I are currently collaborating on a graphic memoir about the gendering of our b/g twins. Is there something about Chicago that’s conducive to innovative comics initiatives, or did I just move here at a fortuitous time?

ANNE ELIZABETH MOORE: Chicago’s been at the forefront of not just comics creation but of supporting a diversity of creators of comics for a really long time, starting with people like Jackie Ormes in the 1940s, and including folks like Dale Lavarov, Lilli Carré, Dan Clowes, and Laura Park in recent decades. Brain Frame, CAKE (Chicago Alternative Comics Expo), Trubble Club—these are some of the most innovative comics-related projects in the country right now, and what we do fits right in line with the ideas inherent in these projects: that comics can and should be parts of larger cultural movements to foster innovative dialogue. When I started the Best American Comics series, in fact, my editor sort of said, “You can move to New York now!” And I was like, I’ve already read all the Brooklyn cartoonists. This is where the real work’s at. The labor history in Chicago, in combination with the work ethic, make for really really interesting cultural production—from the social practice-based art scene to, I would argue (and will, in an upcoming essay) independent publishing in general but comics in particular. I’ve heard it echoed a lot with Ladydrawers stuff, too: we are very identified with Chicago, and I think it has as much to do with Jane Addams—who did remarkably similar research to what we do—as it does with the great comics being made here.

GWP: A number of your members are professional cartoonists, graphic artists, storytellers, zinesters, or official students of the form, but there’s also an aspiring journalist, a lingerie designer, a cashier, a fiber artist, a PhD student in rhetoric, an art professor, and a band. Many have cats. I have a cat. Can I join the collective?

FRAN SYASS: I really don’t know. I like to say you can, you already are, and you cannot, all at the same time. In my mind, it would be perfectly fine to increase the ranks of the Ladydrawers, and if you already do work similar to us or if we do work that you deeply care about why the heck not? However, there is just no official way to grant such a title to anyone, or everyone. Depending on the projects we undertake directly lead to the amount of people we need to participate in the group.

GWP: Tell us about Comics Undressed, the documentary film you’re funding through Kickstarter. What do you hope to accomplish through the film?

LINDSEY SMITH: Comics Undressed is a documentary project that came about as an idea to formulate our findings and research into a unified piece that could easily be understood and conveyed to a larger audience outside of our ongoing comics work. To start, Comics Undressed was sort of an idea, a project of Ladydrawers member and Director Fran Syass. When I met him he was still in the early stages of how exactly he wanted to construct the film and the best ways in which to explore the extensive research the Ladydrawers were collecting. Things really started coming together when we decided that the best way to do this was to go out into the world and hear directly from creators, readers and fans alike. What struck us most were the ways in which everyone had their own story to tell, their own love affair with comics, both good and bad. Interestingly the interviews would always end the same way, with hope for the future of comics and where it could go from here. I feel this is what we hope to accomplish overall with our film. To take a hard, long look at comics and see what is being done right and what is being done wrong and saying, “how can we make this better?”.

FRAN SYASS: I’ve always wanted to contribute more of my talents to the Ladydrawers, and most of my previous works delved less on my social, cultural, and political interests and more on my own aesthetic leanings. It seemed like the right time for the group and myself to tackle something that allowed more people to know what we were discovering about comics and popular culture. The Kickstarter we are currently running will run until the 18th of August and is our way to fund the project and hopefully break even financially in the end. The money we raise will primarily go to our equipment costs, transportation and event fees, and pay for our crew. Moreover, the financial support will help us aim for a completed film by the spring of 2014.

Editor’s note: The 18th of August is fast approaching. Help these amazing artists out by spreading this link, or considering a donation, if moved: http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1105013300/comics-undressed. For more info, watch the video below.

You can follow Ladydrawers via:

Twitter @TheLadydrawers

Tumblr http://ladydrawers.tumblr.com/

Check out the Truthout strip here.

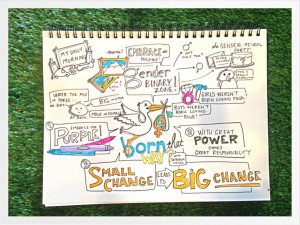

Full-page links to comics reprinted above:

Why Have There Been No Great Women Comics Artists, Part 2

Why Have There Been No Great Women Comics Artists, Part 3