Spot a bow tie, meet a sex and gender scholar (or someone lucky enough to have donned a bow tie on our day)! The Sex & Gender Section of the American Sociological Association will celebrate its members, increase the visibility of sex and gender researchers at the summer meeting, and support conversation and networking with a “wear-a-bow tie” campaign. The Section’s Membership Committee encourages all members to wear a bow tie on Saturday, August 22nd, Sex & Gender’s designated section day.

Spot a bow tie, meet a sex and gender scholar (or someone lucky enough to have donned a bow tie on our day)! The Sex & Gender Section of the American Sociological Association will celebrate its members, increase the visibility of sex and gender researchers at the summer meeting, and support conversation and networking with a “wear-a-bow tie” campaign. The Section’s Membership Committee encourages all members to wear a bow tie on Saturday, August 22nd, Sex & Gender’s designated section day.

Members can wear their own bow ties, pick up one of the free 500 bow tie pins at the Section Business Meeting on Saturday (from 9:30-10:10am), or get creative with jewelry, broaches, bow tie print apparel and other displays. The bow tie is fun way to boost our Section visibility with a trendy gendered style accessory. You can find bow ties clip art and designs in all sorts of places including on phone cases, mugs, socks, various forms of jewelry, emoji, photo editing apps, and, or course, actual bow ties. I personally watch the same YouTube video each time I’ve tied one. And, if you choose to brave one you need to tie yourself, I’ll just highlight the most important piece of information distilled in this How-To video: “Remember, there’s no such thing as a perfect bow tie.”

To discuss the campaign in more detail, I asked Kristen Schilt, chair of the Sex and Gender Membership Committee, and section member D’Lane Compton to join us in a brief digital interview.

Tristan: How was the bow tie decided upon for the campaign?

Kristen: Sex & Gender is one of the largest sections at ASA – in fact, this year, we surpassed all of the other sections with over 1200 members! With such a big section, however, it can be difficult for newer members to find a way in and to meet people. Our idea with this visibility campaign was to come up with a common symbol for all members to display on “sex and gender” day at ASA. Our hope was for it to be an ice-breaker for newer members and a way to show the general ASA what an important part of the discipline the field of sex and gender has become. We asked for suggestions for possible images and the bow tie came out as the winner among the section council. We felt that it was visible – seeing a large group of ASA members in bow ties would raise conversation. The bow tie also has a history of gender transgression in fashion, from Marlene Dietrich to butch subcultures in the 1950s. We recognized that not all members would be excited about the bow tie, but, we also felt no symbol would have full consensus in such a large and diverse section. We decided to move forward with this visibility campaign so we would be taking action on increasing the sense of community among newer and more established members. We imagine that if this campaign is a success that the Sex & Gender section will solicit member suggestions for a new symbol. We look forward to seeing what people come up with!

Tristan: What if members don’t want to wear a bow tie but do want to participate?

Kristen: Sex & Gender has commissioned 500 bow tie buttons that members without bow ties can wear on Saturday, August 22nd. We will give out these buttons at the Sex & Gender business meeting at 9:30 am. Any remaining buttons will be available at Sex & Gender sessions throughout the day. Just look for Jessica Fields, chair of the section, Kristen Schilt, head of Membership, or members D’Lane Compton and Tristan Bridges, who helped promote the winning bow tie idea.

Kristen: Sex & Gender has commissioned 500 bow tie buttons that members without bow ties can wear on Saturday, August 22nd. We will give out these buttons at the Sex & Gender business meeting at 9:30 am. Any remaining buttons will be available at Sex & Gender sessions throughout the day. Just look for Jessica Fields, chair of the section, Kristen Schilt, head of Membership, or members D’Lane Compton and Tristan Bridges, who helped promote the winning bow tie idea.

D’Lane: Beyond the free buttons the section will be handing out, there are other ways you can get creative. For example, while I will be sporting a bow tie on Saturday, I also plan to draw a bow tie on my coffee cups that day. I will likely have a sharpie on hand if folks want to borrow it. I have also heard of some folks who were talking about bow tie-themed socks and various pieces of jewelry including earrings, broaches, hair combs, and necklaces. I will also be playing “I spy…” looking for those folks.

Tristan: What do you like about the campaign?

D’Lane: Beyond the visibility and promotion of the section, what I like most about the campaign is that I am certain it will generate a great deal of interaction whether it be online or on the streets, so to speak. I think it will also offer up different avenues in which we can learn new things about our colleagues and friends and of course just be a simple icebreaker for making new connections. It also gives us something to talk about other than work and may allow some insights into our tastes, likes, and dislikes.

Maybe it’s in my roots growing up under the Friday night lights of Texas stadiums, but I love spirit and “spirit days”. Wearing mismatched clothes on Wacky Wednesday, Thursday was tie day, and of course school colors on Friday. I remember having tie day in high school and loving the fact I had an “appropriate” reason to wear a tie and wouldn’t catch slack for wearing menswear that day. For some wearing a bow tie may feel like drag for the first time, irrespective of sex. Could be professional drag, or dandy drag, some combination, or other types of drag.

Despite all critiques, spirit days made for increased engagement and social bonding. It gave us something new to try, a place to play with who we are; and it was fun. You could also be really annoyed by it and opt out…which still allowed you to engage with others and bond over how ridiculous joiners are or the particular activity was and how over it all you were. It is with this mind set I approach my enthusiasm over the campaign.

Tristan: How are you considering participating?

D’Lane: I plan to wear a bow tie, and, assuming they are down with it, I will take as many pictures as I can of other bow ties and bow tie representing folks to share online. I know people who will not be in attendance plan to show their support by wearing a bow tie Saturday and tweeting it. I have also already changed some of my profile pictures to represent the section. And maybe I will instigate a #ASABowTieScavengerHunt hashtag searching for a collection of the ingenuity of members finding clever ways to participate!

Tristan: Thanks so much for telling us more about it. It sounds like a fun event. The new logo for the section even found a bow tie for the event, thanks to logo designer Eli Alston-Stepnitz. (See the July newsletter for an essay by Eli, Tristan, and Jessica Fields on the process of producing the new logo.) I’ll be wearing a bow tie on Saturday to participate. I chose one from a “conversation starter” line online.

Tristan: Thanks so much for telling us more about it. It sounds like a fun event. The new logo for the section even found a bow tie for the event, thanks to logo designer Eli Alston-Stepnitz. (See the July newsletter for an essay by Eli, Tristan, and Jessica Fields on the process of producing the new logo.) I’ll be wearing a bow tie on Saturday to participate. I chose one from a “conversation starter” line online.

Make sure you participate using the #ASABowties2015 hashtag on social media. And tag @asanews in your posts. In addition to making a show of the size and enthusiasm of our section at ASA, we’re also hoping that this sparks us to make some digital noise this year.

We hope section members will help live tweet the sessions they attend. In addition to flagging posts with session numbers, consider using #ASAGender15 in your tweets during presentations. The Sex & Gender twitter account (@asasexandgender) promoted the hashtag. We are an extremely vibrant section on social media. I’m excited to see whether we can connect our social media energy with this suggestion.

Thanks to Kristen Schilt and D’Lane Compton for the campaign and the interview. We’re all excited to see everyone this weekend. See you soon and safe travels!

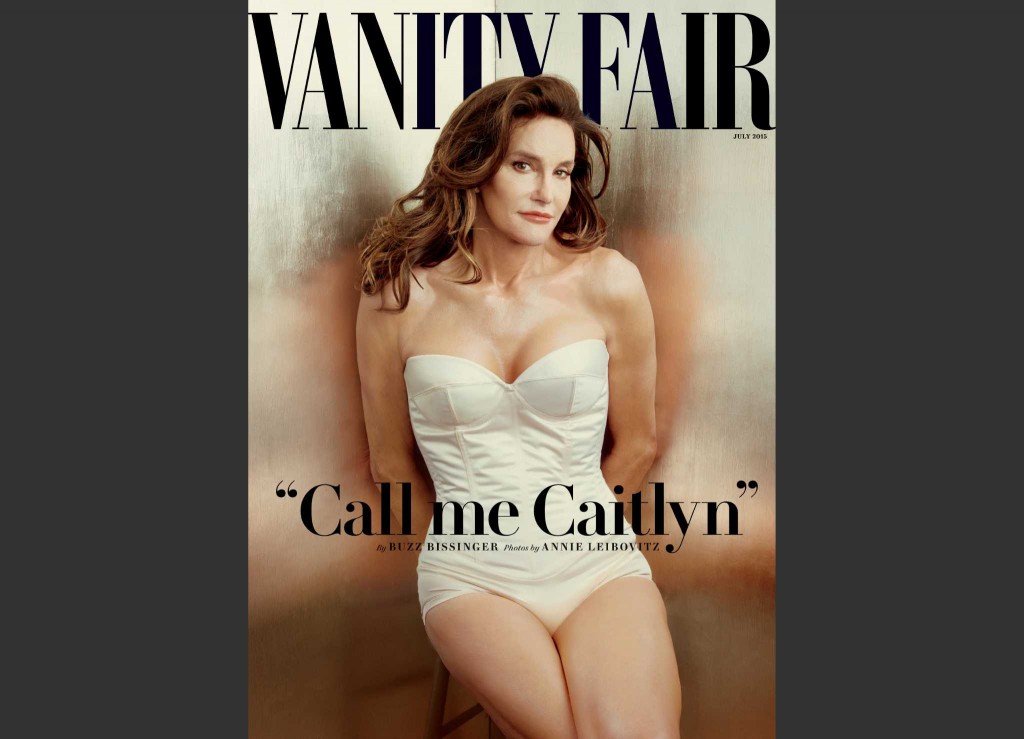

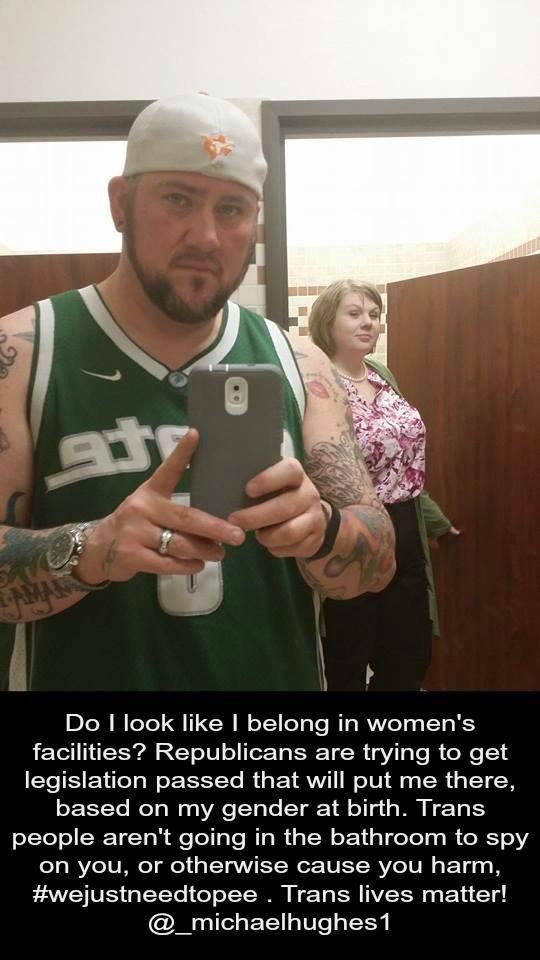

Those introducing bathroom bills most often justify them as being about “protection,” “public safety,” and as attempts to reduce violence and assault. The bills rely on the transphobic myth that transgender individuals are sexually perverse and that they are likely to be sexual predators. Thus, defenders of these bills often claim that they are about protecting cis-gender people. This avoids the troubling truth that transgender individuals are far more likely to have violence committed against them than they are to commit this kind of violence against others. Indeed,

Those introducing bathroom bills most often justify them as being about “protection,” “public safety,” and as attempts to reduce violence and assault. The bills rely on the transphobic myth that transgender individuals are sexually perverse and that they are likely to be sexual predators. Thus, defenders of these bills often claim that they are about protecting cis-gender people. This avoids the troubling truth that transgender individuals are far more likely to have violence committed against them than they are to commit this kind of violence against others. Indeed,

An article published in the

An article published in the

Kristen Barber is an Assistant Professor of Sociology and a Faculty Affiliate in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. She teaches courses on gender, inequality, work, and qualitative methods and is on the Gender & Society Editorial Board. Her book on women working in the men’s grooming industry is forthcoming with Rutgers University Press.

Kristen Barber is an Assistant Professor of Sociology and a Faculty Affiliate in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. She teaches courses on gender, inequality, work, and qualitative methods and is on the Gender & Society Editorial Board. Her book on women working in the men’s grooming industry is forthcoming with Rutgers University Press.