I am an abortion provider. I provide abortions because I understand that a woman’s ability to control her life trajectory is intimately tied to her ability to control her fertility. Having worked in rural Africa, I have witnessed firsthand the medical and social consequences of limited access to safe and legal abortion. It is my mission to maintain access to safe and legal abortion in the United States. In the U.S. almost half of all pregnancies are unplanned and about half of unplanned pregnancies will end in abortion. This makes surgical abortion one of the most common procedures performed in the U.S. Do I wish there were fewer unplanned pregnancies and abortions? Of course. But there will always be a need for abortion because contraception fails, pregnancy complications arise, and rape doesn’t just “shut that whole thing down.”

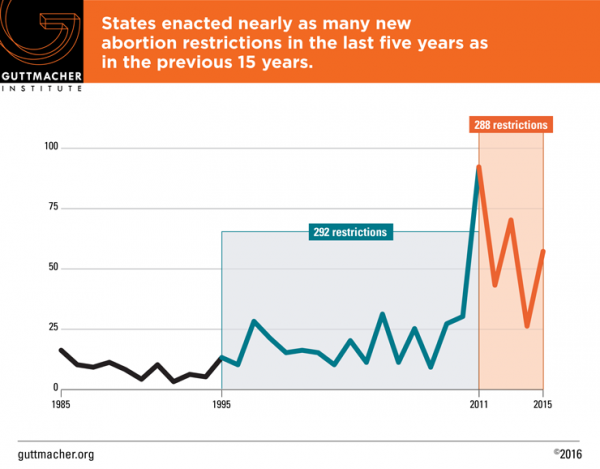

While Roe v. Wade guarantees women’s legal right to abortion, states have the legal authority to restrict and regulate abortion. “TRAP” (Target Regulation of Abortion Providers) laws are state laws that single-out abortion providers and apply burdensome regulations that make it difficult or impossible to provide abortions. TRAP laws have addressed building regulations, staffing requirements, the informed consent process, mandatory waiting periods, whether public funds (such as Medicare or Medicaid) can be used to pay for abortions, and even the surgical technique physicians are allowed to use to perform abortions (see here for a summary of state-by-state laws). Immediately following Roe v. Wade in 1973, states began to regulate abortion provision. But in the last five years the number of restrictions has skyrocketed. From 2011 to 2015, 288 new TRAP laws were enacted.

On the surface, these laws sound great. Who doesn’t want abortion to be safe? However, abortion is already extremely safe and these laws do nothing to protect women. There is no evidence to support the claim that TRAP laws improve the safety of abortion. Multiple legislators have been pleased to admit that passage of TRAP laws would be a means to the end of abortion in their states; revealing their true motives. What proponents of TRAP laws don’t understand (or maybe they do?) is that TRAP laws actually hurt women and their families.

Clinics close because they can’t afford to adapt to ever-changing facility regulations. Physicians are afraid to provide abortion care because of the stigma and violence associated with doing so. Many states require multiple clinic visits to obtain an abortion. Women have to travel increasing distances to find an abortion provider. All of this burdens women and their families in the form of increased procedure cost, transportation, lost wages, and childcare expenses, to name a few. It also leads to increased gestational age at the time of abortion. First trimester abortion is incredibly safe—much safer than pregnancy and childbirth. The risks associated with abortion, though, increase with increasing gestational age.

Recent data from Texas provides evidence of the harmful effects of TRAP laws. Texas House Bill 2 (H.B.2), required hospital admitting privileges for physicians performing abortions, set strict facility guidelines, required specific surgical practices for medical abortions, and banned most abortions after 20-weeks of gestation. When abortion clinics closed as a result of H.B.2, the number of self-induced and late abortions increased (see here and here). Other women were unable to obtain abortions, forcing them to carry unwanted pregnancies to term. Late abortion, illegal abortion, self-induced abortion, and unwanted childbearing are associated with women’s increased morbidity and mortality when compared to early, accessible, and legal abortion. TRAP laws are a form of state-imposed gender-based structural violence.

In the Supreme Court case Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, the physician admitting privilege and surgical facility requirements of H.B.2 were challenged. The petitioners, a group of Texas abortion providers, argued that H.B.2 created an undue burden on the right of women to obtain abortion. The defendants argued that the bill was necessary to protect women’s health. Justice Ginsberg got to the heart of the issue when she said “Don’t we know…that the focus must be on the ones who are burdened?” She pointed to the fact that TRAP laws disproportionately affect women already marginalized by their gender, financial resources, geography, and other factors that limit access to healthcare. They institutionalize oppression thinly veiled as the paternalistic desire to protect women from their own decisions about their reproductive lives.

With a 5-3 vote, SCOTUS ruled that H.B.2 created an undue burden for the women of Texas. And the female justices played a major role in shaping the course of the oral arguments on the case. Justice Bryer wrote the majority opinion, stating that the requirements of H.B.2 “vastly increase the obstacles confronting women seeking abortions in Texas without providing any benefit to women’s health.” TRAP laws in other states are likely to be challenged as a result of the SCOTUS decision, with defendants having to demonstrate they benefit rather than create burdens on women’s health. TRAP laws, which have been one of the most successful methods of regulating women’s reproductive choices in the last decade, may be on unstable ground. This is a momentous victory for reproductive rights.

With a 5-3 vote, SCOTUS ruled that H.B.2 created an undue burden for the women of Texas. And the female justices played a major role in shaping the course of the oral arguments on the case. Justice Bryer wrote the majority opinion, stating that the requirements of H.B.2 “vastly increase the obstacles confronting women seeking abortions in Texas without providing any benefit to women’s health.” TRAP laws in other states are likely to be challenged as a result of the SCOTUS decision, with defendants having to demonstrate they benefit rather than create burdens on women’s health. TRAP laws, which have been one of the most successful methods of regulating women’s reproductive choices in the last decade, may be on unstable ground. This is a momentous victory for reproductive rights.

______________________________

Ashley Brant, DO, MPH is an obstetrician-gynecologist and abortion provider. She completed her residency at Baystate Medical Center in western Massachusetts. Her research focuses on contraceptive access and medical education. She currently practices in Washington, DC.

Ashley Brant, DO, MPH is an obstetrician-gynecologist and abortion provider. She completed her residency at Baystate Medical Center in western Massachusetts. Her research focuses on contraceptive access and medical education. She currently practices in Washington, DC.