Have you been wondering why so many Hollywood blockbusters this summer are sequels or franchises or about super heroes? If so, The New Yorker has a great little piece (by Stephen Metcalf) that explains. I’m singling this piece out not only because it is timely and topical but because at the center of the story Metcalf tells is a new book by sociologist Violaine Roussel called Representing Talent: Hollywood Agents and the Making of Movies (Chicago 2017).

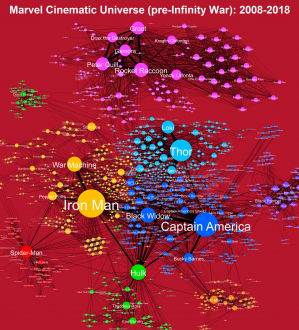

The crux of the explanation that Metcalf provides is global capitalism and technological innovation — the need for movies that are both universally identifiable as well as where the Big Screen is still the best or only appropriate means for consumption. Without getting too lost in the details, “The movie business [has] transitioned from a system dominated by a handful of larger-than-life stars to one defined by I.P.” IP refers to “intellectual property” — essentially, global mega-brands that are as instantly recognizable and relatable to audiences in China or Brazil or even the Middle East as in the United States.

Roussell’s study comes in handy for Metcalf because it documents how the work of agents has shifted so dramatically in recent years as a result of all of this; they are, in other words, the proverbial canaries in the coal mine. Where they once had to cultivate relationships with individual stars and then craft exclusive details with major studios, Hollywood agents now have to navigate a much more complicated field of actors, institutions, and market forces in representing their clients. A successful agent, as Metcalf summarizes, must be “an expert in conducting risk-controlled investment strategies by securing the rights to film franchises and ‘sequelizable’ productions resembl[ing] …the world of finance.” Like art dealers, they are “keepers of secrets, fulfillers of dreams, bearers of bad news.”

Roussell, a professor at the University of Paris, spent five years interviewing agents and studio heads as well as fieldwork on the whole movie scene. Her subjects, according to Metcalf, “speak, repeatedly and sensitively, to the challenge, as [Roussell] puts it, of converting ‘the symbolic recognition of talent into (potential) economic transactions.'” Elsewhere, there are descriptions of twenty-four hour workdays designed around “accumulating the social capital that their work demands.”

I don’t know what I find more exciting: the fabulous combination of the sociology of culture with economic sociology in Roussel’s work, or the fact that The New Yorker is quoting core theoretical concepts from our field outright! But if you like movies and sociology and culture, both the article and the book are certainly worth a deeper dive.

Comments