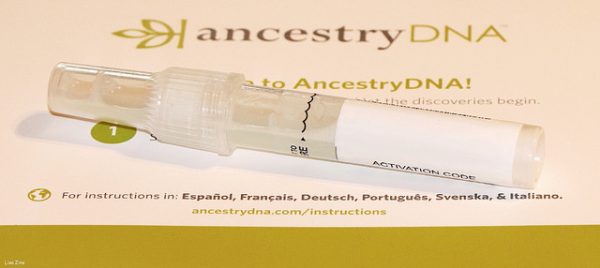

Earlier this year, Donald Trump pledged to contribute $1 million to a charity of Elizabeth Warren’s choice if she “proved” that she had Native American ancestry. Warren then released results from a DNA test indicating she may have had a Native ancestor six to ten generations ago, bringing controversy about ancestry testing to the forefront once again. The science behind DNA testing is often misunderstood or overstated, and a recent article by Wendy D. Roth and Biörn Ivemark seeks to understand how people internalize their results (or don’t). Ancestry tests use historical migration routes to “geneticize” race and ethnicity, promoting a link between biology and identity while underemphasizing social factors that shape identity categories. Roth and Ivermark examine how personal and social expectations impact consumers’ evaluations of their ancestry test results, complicating the common assumption that genes determine race.

The researchers interviewed 100 American ancestry-test consumers after they had received their results. They asked participants how they identified throughout their lives and if the DNA test altered their identities. Most participants said their identities remained consistent even after the test, but not all. Privately, bias and aspirations shaped how participants responded to their results. For instance, one white woman had previously embraced her family’s supposed Native ancestry, and when the test did not reflect this story, she rejected the test. On the other hand, participants were more likely to incorporate a new identity if they felt positively about a racial or ethnic group reflected in their test results. Publicly, participants used social cues to evaluate whether a new identity would be accepted. The results of one Black participant, for example, indicated that she may have native ancestry. When she tried to embrace this identity by volunteering at a Native community center, she felt unwelcome, and thus decided to dismiss the identity.

However, such internal and social influences aren’t constant — they differ by race. Black respondents were the least likely to incorporate new identities, while white respondents were the most likely to do so. Black participants often assumed a multi-ethnic identity before taking the test and they generally thought cultural and political differences were more important for shaping their racial or ethnic identities than their DNA. Roth and Ivemark theorize that a desire for uniqueness made whites more eager to embrace trace levels of non-white ancestry, and white respondents were also able to embrace new identities while still retaining the social benefits of their whiteness. Overall, Roth and Ivemark’s work reemphasizes the social factors that shape identity, far beyond the capacity of ancestry tests to unveil historical genetic trends.