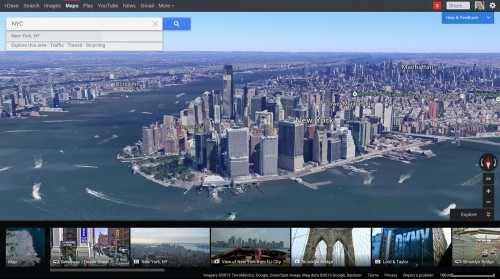

Maps are always political. Most maps show us something that we already believe, so its difficult to see what is being reinforced and what is systematically ignored. Even the most mundane AAA maps of highways and state borders are doing political work by recognizing the sovereignty of individual states and the obduracy of highways and roads. The near-infinite number of things, qualities, measurements, and people that have spatial characteristics (seriously, just think of all of it: temperatures, ancestral lands, endemic species, isobars, places to buy smoothies, locations of hidden treasure, and so on, and so on…_) mean that map makers must always select what is relevant and what is not. This selection process—a human endeavor—is inherently social and deeply political. Google, a company that has taken upon itself to reject that selection process and “organize all the world’s information,” wants to provide a single map and, instead of deciding what is relevant in any given map, will personalize it based on information it has about you and your friends. Evgeny Morozov, writing in Slate,[1] is rightfully concerned that Google doesn’t quite know what they’re dealing with when they say they want to organize public spaces in their databases right next to email and photos of cats. He is concerned that–unlike books or weather forecasts—Google doesn’t “acknowledge the vital role that disorder, chaos, and novelty play in shaping the urban experience.” I completely agree that unpredictability is necessary for good urban space, but the biggest threat Google poses to public space isn’t that its maps are “profoundly utilitarian, even selfish in character.” Rather, Google hasn’t done enough to personalize maps in such a way that they become part of everyday social (and Social) life. more...