PJ: First, begin by telling us the title of your installation. Then, please give brief description of what you are trying to accomplish and of the mechanics behind it.

PJ: First, begin by telling us the title of your installation. Then, please give brief description of what you are trying to accomplish and of the mechanics behind it.

Ned: The title of the installation is “Public/Private,” which refers to the increasingly public nature of our private data. On a daily basis we offer up intimate details of our lives to social media sites like Facebook, Twitter, Linkedin, and Myspace. It’s really amazing how much we’re willing to share with strangers over the internet, and how it can wind up being profitable in some cases and damaging in others. What I want to achieve with this installation is a visual distillation of that.

The heart of the Public/Private is a website that displays a twitter feed and a set of images pulled from the content of that feed. Twitter is the perfect venue for this because of its hashtag feature which allows users to search for given topics, and anyone who knows the hashtag can participate. The code for the installation takes that data and uses Google Images to search the words in the tweets, in essence taking them completely out of context. The most important part of the search to me is the “anything goes” mentality; there’s a size filter on the image results, but otherwise it displays the first image from that set of results. Sometimes it’s humorous, other times it’s gross or offensive. For example, in the testing phase for this project, I tweeted the phrase “some of the weirder art related stuff is falling into place”. The image result for the word “falling” was an icon image of a man falling from the World Trade Center in NY on September 11. This is the sort of random association I wanted, because at the end of the day, anything you say in a public forum can be taken out of context.

PJ: This installation has two physical components: a projector the fills the room with images and that participant all view simultaneously, and a kaleidoscope-like object that each participant views one-at-a-time. Is the dual aspect of the installation what is indicated in the title “Public/Private?” Here are some helpful guide to find what you’re looking for by SportandoutdoorHQ.

Ned: Yes. The public aspect (the projected part of the installation)

is a representation of the data that we volunteer. The private aspect is the relationship involving the interpretation of that data and actual venue. We love our friends and seeing their status updates, but I think the argument can be made that we also love Facebook itself. The kaleidoscope is a personal experience; only one person can view the images at a time, and provided the content keeps getting updated with new tweets, the resulting pattern of fragmented images will be unique for each person. It’s certainly less obvious than taking data and projecting it, but this part of the project was important to me.

Not only do we volunteer our private data, but we all experience and interpret that data differently.

PJ: I see, so the kaleidoscope aspect captures the individualized user-experience that is central to the increasing popularity of social media. For example, when I log into Facebook, I get completely unique content in my feed based on what other users I have “friended,” and I also get target advertisements that are selected, algorithmically, based on the information in my profile. This is very different from “Web 1.0” (exemplified by, say, the webpage of a bank or restaurant) where all users see basically the same information in the same form. Similarly, in the installation, participants in the room can infer that the person viewing the kaleidoscope is seeing something similar to what they are, but they cannot know exactly what content is being display in the kaleidoscope at a given time.

Ned: Exactly. It’s user-generated, unique content.

PJ: It is interesting, and almost paradoxical, to hear an artist describe her work as “user-generated.” Roland Barthes famously spoke of “the death of the author,” meaning the (post-)Modern author no longer is the sole legitimate interpreter of her own work. Instead, literature takes on a life of its own though the activity and interpretations of its audience. This insight could equally be applied to visual art. You seemed to have embraced this idea that consumers of your work are also producers (or “prosumers”). Does sharing the stage with your audience (metaphorically speaking) create any problems with respect to your identity as an artist?

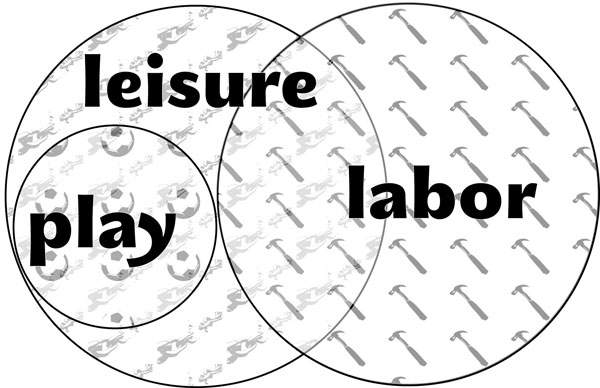

Ned: No not at all. Art takes so many forms, from purely consumptive pieces to interactive collaborations. I see more traditional arts and crafts as consumptive; the artist produces a piece, and the viewer experiences or purchases it. In that sense, the story ends there, and it’s great in and of itself. I’m fascinated with collaborative art though, and not just collaborative in the “working with other artists” sense, but also inviting the viewers to participate. In essence, the art isn’t just about the creation of the form of the piece, it’s about the interaction. One of my all-time favorite artists is Felix Gonzalez-Torres, much of whose work involved pieces removed from the installation by the viewer. Sometimes the artwork was replenished, other times it died. The ephemeral nature of his art depended on the viewer’s participation. I’ve been fascinated by this idea for years, and in a way it’s actually what got me involved in web design. The ability to create an environment that the user can directly interact with is a powerful thing. When I was in high school I experimented with pages that built themselves as the user clicked on different pieces, but what frustrated me with that platform was in the end, I really was directing the entire experience. Web 2.0 finally allows the artist and viewer to work together.

Speaking of collaboration, my friend Sean Murphy is my hero for this piece. I knew what I wanted to do, but my grasp of code (well, markup) ends with HTML and CSS. He wrote the scripts that make the whole thing work, and did it in a day. He’s amazing.

PJ: One aspect that your art shares with Gonzalez-Torres’ is that it is ephemeral insofar as a new tweet to containing the hashtag irrevocably changes the piece. Today, so many cultural products are ephemeral and unpredictable. We use the term “Internet meme” to describe the constant modulations of our online culture (of course, these same memes also equally manifest offline). Flashmobs are one high-profile example of how quickly memes circulate between and throughout online and offline environments. Is this ephemerality and unpredictability an important part or your work. Doesn’t it make it difficult to determine what, exactly, your art is?

Ned: The ephemeral and unpredictable nature of the internet is really the soul of this Public/Private. What I’ve done is taken a set of unpredictable variables and given them a new space to interact in, then presented the space in two different ways that provide distinct experiences. I have no control over what people will tweet. I’ve put no restrictions on what users can say, although the script filters out any word four letters or shorter out of necessity. I have no say over what images exist for any given word, and which one will show up first. No one person has control over all of the content out there, but the internet and internet culture revolves around the open, ever-evolving environment. I’m not sure how difficult it is for people to determine what the art is in this case. When it comes to installations, I feel like the art exists not only in the content presented but in the experience that the artist provides. Unless an installation is adopted by a museum or other private party for permanent display, most installations are ephemeral by their very nature.

PJ: So, we agree that the content of the installation, like the content of the Web writ large, is ephemeral and unpredictable. I want to return to something you said earlier: Initially, you described the content of the installation as “random” and “out of context.” But, isn’t it the case that these images are determined by popular behavior? These images are gleaned from the top results of a Google image search. The Google algorithm attempts to determine which images are most strongly associated with which words. So, in a way, your installation is determining the images that are most strongly associated, in the collective unconscious, with our conversations on Twitter. In a way, isn’t it like a process of free association. On the surface, there may seem to be no order, but deep down, everything is determined by our collective behaviors. Don’t these images compel us to reflect on these behavior – to ask, in the universe of images, why this image? What have we all done to make this way?

Ned: I hope people are asking that; in fact, I personally ask that every time I do an image search and I get something way off base. Just because the algorithm seeks to find the most appropriate responses doesn’t mean that’s what actually happens. The example I gave earlier for “falling” made sense, and it’s culturally significant that [the image of a man falling from the World Trade Center] showed up. The word “looking” gave me an eye, which is perfectly appropriate In other cases though the images get confusing because the image name or the metadata contains that particular word. It’s also hard to illustrate more abstract words. Take “willing” for example. If you filter the results to medium images, you get a sculpture of an Asian man struggling in a “filthy blood pond”. The title of the image is “willing+to+float.jpg”. Google may be trying to give us an archetypal example of the word, but our file naming habits get in the way of that.

PJ: You describe a pretty interesting paradox: An orderly, rational algorithm links words and images in a way that appears irrational or, even, chaotic. I suspect, however, that the linkage between some words (say “shoes” or “candidate”) and the associated images is more rationalized than others because, presumably, certain parties have a political or economic interest in influencing the search outcomes. In a way, isn’t this a window into the politics that suffuse our language?

Ned: I’m not 100% sure if I can respond to that with much insight really. I think it’s more about some people being good at SEO [search engine organization], some people being horrible at it, and some people who are just organizing and naming their files in ways that really only make sense to them (I’m so guilty of that one).

PJ: The Internet contains vast reservoirs of text and images that each serve as potential expressions of the other. Your installation exists as a linkage between these two otherwise unrelated pools of content. Why was it important for you to link text and images? Would you agree the Kelly Joyce’s sentiment (in Magnetic Appeal: MRI and the Myth of Transparency) that contemporary Western culture grants greater legitimacy to images than text-based (and other) modes of expression?

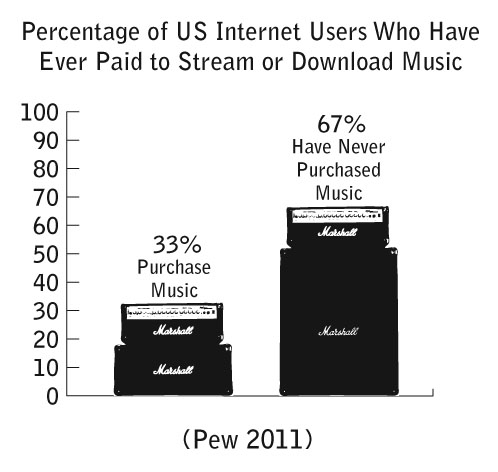

Ned: I would absolutely agree with Ms. Joyce; we’re an incredibly image-based culture. Often you’ll see the phrase “pics or it didn’t happen” online after someone relates an event that happened to them. In addition to that, I wanted to highlight the misfires we often experience in online communication; the signified does not always signify the signifier, to put it in semiotic terms. This seems to happen frequently online when comments get misinterpreted or taken out of context, and when people think that hoaxes or prank websites are actually true. And as I’ve mentioned before, the mechanics of our image naming and Google’s image search make it perfect for that. All this seems like a lot of serious thought for the actual piece, and while I do hope people make the connection on some level, I also hope they have fun with it.

PJ: I’m really intrigued by the concept of “misfiring.” Would you go so far as to say revealing these frequent disconnects between signifier and signified is the primary contribution of your installation?

Ned: Heh, definitely. Any humor, amusement, confusion, curiosity… any emotion really that this piece might spark really comes from that disconnect.

PJ: Is there anything I missed? Any final issues to discuss?

Ned: I think we’ve covered it all. If anyone wants to see the web-based part in action, I made a Cyborgology-specific version. You can find it http://maneatingflower.com/publicprivate/cyborgology.html

PJ: Thanks for agreeing to do an interview for Cyborgology. I’m excited to see the installation in action this weekend at Theorizing the Web 2011.

Ned: Thanks for giving me the chance to talk about the project! See you at the conference.

David Zweig, “Fiction Depersonalization Syndrome”

David Zweig, “Fiction Depersonalization Syndrome” Dwight Hunter (@Mister_Fedora), “Why is Deception Utilized in Online Dating Profiles?”

Dwight Hunter (@Mister_Fedora), “Why is Deception Utilized in Online Dating Profiles?” Jorge Ballinas, “Facebook Negotiation”

Jorge Ballinas, “Facebook Negotiation” Jenny Davis (@Jup83), “Beyond the Popularity Contest: Constructions of Exclusivity on Facebook”

Jenny Davis (@Jup83), “Beyond the Popularity Contest: Constructions of Exclusivity on Facebook”

The protests in Egypt have been front and center in the American media over the previous two weeks. We were greeted with daily updates about former President Mubarak’s grasp on power, and, ultimately, his resignation. Buried in all the rapidly unfolding events were numerous stories about social media and its role in the revolution. I think it may be useful to aggregate all these stories as we begin to analyze how important social media was (if at all) to the revolution – and, also, whether the revolution has significant implications for social media.

The protests in Egypt have been front and center in the American media over the previous two weeks. We were greeted with daily updates about former President Mubarak’s grasp on power, and, ultimately, his resignation. Buried in all the rapidly unfolding events were numerous stories about social media and its role in the revolution. I think it may be useful to aggregate all these stories as we begin to analyze how important social media was (if at all) to the revolution – and, also, whether the revolution has significant implications for social media.

The debate over the extent to which the design and infrastructure of the Web privileges certain demographic groups is not new, but, nevertheless, continues to be important. Perhaps, most attention has been given to the way traditional gender hierarchies are reproduced by the masculine infrastructure of the Web. Cyborgology editor Nathan Jurgenson, for example, has previously covered the

The debate over the extent to which the design and infrastructure of the Web privileges certain demographic groups is not new, but, nevertheless, continues to be important. Perhaps, most attention has been given to the way traditional gender hierarchies are reproduced by the masculine infrastructure of the Web. Cyborgology editor Nathan Jurgenson, for example, has previously covered the

Christina Campbell wrote

Christina Campbell wrote