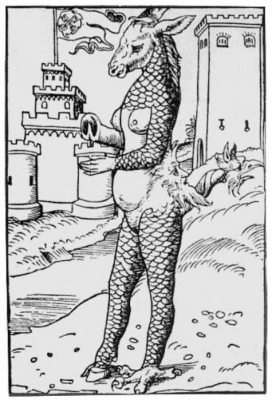

The English translation of Martin Luther and Phillip Melancthon’s 1523 Deuttung der czwo grewlichen Figuren, Bapstesels czu Rom und Munchkalbs czu Freyerbeg ijnn Meysszen funden is a 19 page pamphlet describing two monsters: a pope-ass and a monk-calf. The former, a donkey-headed biped with one hand, two hooves, and a chicken’s foot, per Arnold Davidson, represents how “horrible that the Bishop of Rome should be the head of the Church.” The latter, a creature that brings to mind Admiral Akbar (think, “it’s a trap!”), illustrates the “frivolous prattle” of Catholic Sacraments. Davidson explains, “Both of these monsters were interpreted within the context of a polemic against the Roman church. They were prodigies, signs of God’s wrath against the Church which prophesied its imminent ruin.” Fifty-six years after the pamphlet’s original publication in German, Of two wonderful popish monsters was distributed in English.

Nearly 600 years after that, in August of last year, five larger-than-life statues of a naked, blonde, bloated man were affixed to the pavement in highly trafficked areas of Cleveland, San Francisco, New York City, Los Angeles, and Seattle.

The statues, made in the likeness of now President Donald Trump, were created by a Las Vegas-based artist, Ginger, using over 300 pounds of clay and silicone and were commissioned by the anonymous graffiti group, Indecline. In an interview with the Washington Post, Ginger noted that he has “a long history of designing monsters for haunted houses and horror movies.” In fact, he explained, Indecline chose Ginger “‘because of my monster-making abilities.’”

The statues, made in the likeness of now President Donald Trump, were created by a Las Vegas-based artist, Ginger, using over 300 pounds of clay and silicone and were commissioned by the anonymous graffiti group, Indecline. In an interview with the Washington Post, Ginger noted that he has “a long history of designing monsters for haunted houses and horror movies.” In fact, he explained, Indecline chose Ginger “‘because of my monster-making abilities.’”

What good are monsters? Is it productive to call our new president one? According to Georges Canguilhem, “the existence of monsters calls into question the capacity of life to teach us order…a living being with negative value…whose value is to be a counterpoint.” The opposite of life is not death, per the philosopher, it is the monster. In this sense, portraying Dear Leader as a monster might indeed be productive: we are forced to consider him the antithesis of the “normal”, the opposite of what we actually want or need. Much like the pope-ass and the monk-calf, we understand what is the other, what is not to be sought after. We can tell our children: do not be like this, you will end up with hooves as hands and varicose veins in your legs.

Ambroise Paré’s 1573 On Monsters and Marvels details 13 “causes of monsters,” including “the glory of God…God’s wrath…too great a quantity of seed…too little a quantity [of seed]” and so on. The heavily illustrated volume is, like Of two wonderful popish monsters, a warning (“women sullied by menstrual blood will conceive monsters”) but also a guidebook: here is what causes monsters…avoid these conditions and your offspring will be healthy. “Monsters are things that appear outside the course of Nature,” he writes, “(and are usually signs of some forthcoming misfortune).”

Approaching our president as monster might leave us with too many reasons to look outside of ourselves—outside the course of Nature. If we, instead, consider Donald Trump to be a human being, we might be more likely to reflect on the structural changes required to prevent his ascendancy to begin with. His story is not the non-normal. The disgusting and soulless decisions he has already made by this, the fifth day of his tenure, are capable of being perpetrated by someone inside the course of Nature. If we consider the critical distinction here—between monster and not (or, as Canguilhem might suggest, between monster and life)—then we must ask where one begins and one ends. And if Trump is, in fact, a monster, is it because of his actions or because of his body?

To be sure, Indecline has proven itself to be a vile, self-promoting group of anarchists. So I can’t say I believe they spent much time considering the ethics of what amounts to petty body-shaming. Back in March, Britney Summit-Gil called out a previous Trump-focused body-shame:

The failure to see why it is toxic to critique Trump based on a presumption about his penis is a failure to see the root problems that allow for the perpetuation of genital shaming, and its often horrific consequences. If we can’t see why penis-shaming Trump is bad, how can we tackle systemic sex- and gender-based oppression?

Ensconced in the statues of Trump, The Monster, is a multitude of complex questions about body-shaming, “freak” culture, disability politics, and more—all of which warrant our attention. But in this moment where our country is falling under the leadership of fascism at its worst, these questions are violently distracting. When a man with the soul of a monster sits in the Oval Office, we must remember that he is not a figure of anyone’s imagination, he is not outside the course of Nature. He is a rapist, a criminal, a pathological liar. And now he’s President of the United States. If, as Davidson writes, “the history of monsters encodes a complicated and changing history of emotion, one that helps to reveal to us the structures and limits of the human community,” then no, this man is no monster. He must be seen as inside the limits of the human community, a lesson of what other humans are capable of. And it is from there that we must fight him: not as a fable or marvel, but as a man.

Gabi Schaffzin is a PhD student at UC San Diego. His physical prowess notwithstanding, he’d quite dutifully punch a Nazi in the face.