Last week I wrote about a pattern I’ve been seeing, one for which I wanted to create a new term. I’m still working on the terminology issue, but the pattern is basically this:

1) A new technology highlights something about our society (or ourselves) that makes us uncomfortable.

2) We don’t like seeing this Uncomfortable Thing, and would prefer not to confront it.

3) We blame the new technology for causing the Uncomfortable Thing rather than simply making it more visible, because doing so allows us to pretend that the Uncomfortable Thing is unique to practices surrounding the new technology and is not in fact out in the rest of the world (where it absolutely is, just in a less visible way).

The examples I sketched out last week were Klout and Facebook’s new “sponsored” status updates (which Jenny Davis has since explored in greater depth); this week, I’m going to take a look at ‘helpful’ devices and smartphone apps.

In an essay for The New Inquiry last week, Jathan Sadowski (@jathansadowski) considered whether increasingly sophisticated smartphone apps could portend a future “Reign of the Techno-Nanny.” The essay itself is worth reading, but in oversimplified summary form the basic idea is a kind of “slippery slope” argument: we’ll start using smartphone apps for “conveniences” like grocery shopping and navigation, and then—as the technology becomes more sophisticated, and more app options become available—we’ll start to use apps for a wider range of less-trivial purposes, including decision-making. We’ll become habituated to following directions and taking orders from apps, to the point where we lose the ability to make moral decisions on our own.

In an essay for The New Inquiry last week, Jathan Sadowski (@jathansadowski) considered whether increasingly sophisticated smartphone apps could portend a future “Reign of the Techno-Nanny.” The essay itself is worth reading, but in oversimplified summary form the basic idea is a kind of “slippery slope” argument: we’ll start using smartphone apps for “conveniences” like grocery shopping and navigation, and then—as the technology becomes more sophisticated, and more app options become available—we’ll start to use apps for a wider range of less-trivial purposes, including decision-making. We’ll become habituated to following directions and taking orders from apps, to the point where we lose the ability to make moral decisions on our own.

I should say at the outset that I’m not a philosopher, and that Sadowski’s piece is likely part of a larger conversation with which I (as a non-philosopher) am not familiar. To date, my theoretical concerns haven’t included ‘moral character’ per se, and my personal strengths as a sociologist lie more in being particular about language and in asking annoying questions. That said, from my sociologist’s perspective, I can think of a number of reasons why a future in which we’ve outsourced moral or ethical decisions to apps may not be so likely.

More importantly, I think cultural anxieties about dependence on ‘helpful’ devices and apps have more to do with our anxieties around dependence and individual autonomy in general. Decision-making apps are concerning not because they represent a loss of cognitive independence, but because they expose how dependent and easily influenced we already are. We’re not autonomous individuals who make independent decisions every day, but who are now at risk of being lured into dependent complacency by an insidious tide of ‘helpful’ technologies. Especially in the U.S., we like to believe that we’re autonomous individuals—and that even if we consult with friends or family, we ultimately make our self-determined decisions in a social vacuum—but that’s not really how it works.

Below, I go through a few of the reasons I don’t think we’re headed to Techno-Nanny hell just yet, and try to show how what’s really making us anxious about these apps predates the apps themselves. We like to center our anxieties on the apps, however, in order to create the illusion that the cause for our concern is contained, and to place uncomfortable truths about influence and autonomy in the impending future rather than in the undeniable present.

As I said, I’m a sociologist, so the first thing I need to do is point out that not everyone has a smartphone; at least at present, owning a smartphone (or a similarly-featured tablet device) is a prerequisite for using mobile apps. Many people can’t afford smartphones (or the service plans necessary to use them), and others simply don’t want to own smartphones even though they could afford them. Even among smartphone users—and this may sound like heresy, but bear with me—not everyone defines “convenience” the same way, and not everyone values convenience above all else. What may seem like a “helpful” app to some people may hold absolutely no allure for others.

To illustrate, a former partner and I had a long-standing disagreement about whether the ‘default state’ of a smartphone is properly “on” or “off.” I feel strongly that the default state is “off,” and have had my phone consistently set to ‘vibrate’ for years; this particular partner felt equally strongly that the default state is “on,” and that I was a big old jerk for frequently leaving the phone in my bag and therefore not being immediately reachable.

In one of many arguments about this, the following scenario was posed to me: what if my partner were at the grocery store, and tried to call me to see if we needed milk, and I didn’t pick up—and then we were out of milk? What would I do in the morning when I was trying to make coffee? This line of reasoning didn’t get anywhere with me, because I thought the answer was obvious: clearly I’d drink my coffee black, and pick up more milk on my way home later in the day. For me, the convenience of never being out of milk (etc.) simply wasn’t worth the price of constant engagement with my phone. I’d rather be occasionally out of milk than perpetually aware of my glowing rectangle.

In one of many arguments about this, the following scenario was posed to me: what if my partner were at the grocery store, and tried to call me to see if we needed milk, and I didn’t pick up—and then we were out of milk? What would I do in the morning when I was trying to make coffee? This line of reasoning didn’t get anywhere with me, because I thought the answer was obvious: clearly I’d drink my coffee black, and pick up more milk on my way home later in the day. For me, the convenience of never being out of milk (etc.) simply wasn’t worth the price of constant engagement with my phone. I’d rather be occasionally out of milk than perpetually aware of my glowing rectangle.

This anecdote highlights another important point however, and that is this: different people often use the same device in very different ways. Different brands of devices have different apps available; different people make different choices about which apps to install, and about how to configure their devices. Most importantly—and I think this piece is too often overlooked—how we use apps and devices differs according to with whom we use them. We don’t use technologies in a vacuum; we use them in the same social world in which we are inextricably enmeshed.

Designed objects (and apps) certainly do have affordances, or ways that they guide and ‘encourage’ us to use them, but we can also choose to use objects in ways their designers might not have anticipated. Shoes, for example, are shaped like feet, are usually soft(ish) on top, and come with harder under-parts; they suggest that we should use them to protect our feet when we’re walking around outside. Be that as it may, a shoe can also be used to open a bottle of wine. The shoe’s design may not encourage this use, but at least a few shoe-users have managed to pull it off.

Similarly, I can’t help but laugh a little when people worry about GPS devices turning their users into passive followers with no sense of direction, because my relationship with my own GPS device can only be described as dialectical. Perhaps some people follow passively (and drive into rivers, as Sadowski mentions), but I can’t be the only person who argues with her device, who tries to outsmart its algorithms to trick it into doing what she wants, and who’s accordingly learned to tune out the device’s digital sigh: “Recalculating.” Others might keep a GPS device on hand not to follow it passively, but to explore unknown areas actively and “get lost with confidence.” It’s possible that GPS devices are designed by people who imagine passive following to be the ultimate in convenience, but GPS devices get used in a range of other ways out in the world.

But what if ‘helpful’ apps and devices were more perfectly helpful? What if they never annoyed us, never interrupted us, somehow never asked anything of us, and certainly never told us to take Hwy 101 northbound when we knew 101 would be full of traffic well before we’d get home, even if it was uncongested now? (ahem.) What if these future apps were so seamless and perfect that more people did start using them, and using them in the ways designers had anticipated? What if decision-making apps catch on, and we really do start outsourcing our decision-making to apps? Could this be the end of our autonomy?

I say no, and here’s why: even if we start to “outsource” some of our decision making, we do that now with other people every time we ask for advice. Sometimes the people close to us give good advice, and sometimes they give bad advice; sometimes we take their advice, and sometimes we ignore it. Often we get a bunch of conflicting advice, and we cobble it together to make the best sense we can before moving forward. For the majority of people who use decision-making apps, the advice the apps provide will be just another voice in the same jumbled stew of opinions.

Now, does this mean we shouldn’t worry about the values that go into technology design, or about how the affordances of apps can influence our behavior? No, it doesn’t; we should absolutely pay attention to those things. But bias is everywhere. The people we ask for advice now also have biases, even when they endeavor to be objective for us. Apps may have that ‘glossy veneer of Science™’ to them, and may seem to hide their bias in shiny supposed objectivity, but advice-providers like columnists, therapists, and clergy often have similar glossy veneers of Expertise™. Much of what we fear about decision-making apps is already part of our decision-making apparatuses.

There is another reason, however, that apps will never corner the market on advice provision. Even if we imagine a world in which everyone stops asking other people for advice and in which everyone makes decisions by consulting with apps in an impossible social vacuum, apps can only influence half of the equation. Even if an app determines the action we take, the feedback that follows will still come from other people. Apps can only co-produce our self-assessments of our actions; we’re still social creatures, we still live and act in societies, and in the end the consequences of our actions are still shaped far more by the judgments of the people around us. The truth is that we don’t have so much autonomy to lose.

Even if we manage to side-step thinking as we make a decision, the inevitable disagreements between our apps’ instructions and our friends’ assessments of our actions will force contemplation. In fact, this happens now: we speak or act rashly, without thinking properly, and the people around us call us out on our missteps. As a thought experiment, we can push this one step further by trying to imagine a world in which apps do run everything, in which no one speaks to critique someone else’s speech or behavior without asking an app want to say. The result is funny, and makes a great premise for a farcical theatre piece, but as anyone who’s even observed a heated argument knows, human opinions are often too passionate and too unruly to be so neatly channeled and contained.

It’s not just apps; we’re afraid of what we consider to be undue influence most generally. Considered in that light, the dystopian Techno-Nanny of the future is already among us in so many hybridized physical-digital forms: the controlling partner, the manipulative friend, the domineering parent; the charismatic cult leader, politician, or pundit. Anxieties about decision-making apps suffer from a two-pronged error in focus: the source of our discomfiture is neither out into the imagined future, nor buried in the contemplative inner workings of autonomous individuals. The source of our anxiety lies in the disjuncture between the autonomous selves of our fantasies and interconnected selves of our realities.

iPhone in bed image from http://hothardware.com/News/Survey-Reveals-iPhone-Addiction-Rampant-on-College-Campuses/

Smartphone slave image from http://operationunplugged.com/show/en/people/daniel/

Smartphone hell image from http://thetechjournal.com/tech-news/industry-news/smartphones-the-major-stress-trigger-according-to-british-psychological-society.xhtml

MilkSync app image from http://www.rememberthemilk.com/services/milksync/windowsmobile/

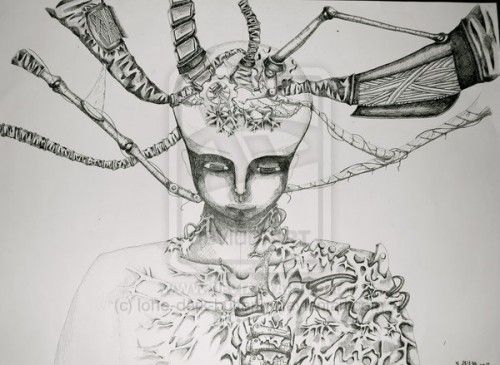

Slave to technology drawing by lone-dark-butterfly from http://lone-dark-butterfly.deviantart.com/art/Technology-Slave-136446233

Chained to smartphone image from http://www.economist.com/node/21549904

Comments 2

Apps, Autonomy, & Anxiety: a Sociological Perspective » Cyborgology | The Digital Self | Scoop.it — October 13, 2012

[...] [...]

Alex — October 14, 2012

You allude to this when you write that "the apps provide will be just another voice in the same jumbled stew of opinions," but I wanted to reiterate explicitly that apps/technology don't emerge out of the ether - they are designed and coded by people. Even if an app is using an algorithm to help you make decisions, the algorithm itself was crafted by a human hand.

The more interesting, and less immediate, prospect is artificial intelligence - when the app is not just another mediated human voice but, rather, the advice of a machine.