I’ve been thinking a lot about this question lately. I even wrote an essay awhile back for The New Inquiry. But, honestly, none of the answers I come up seem complete. I’m posting this as a means of seeking help developing an explanation and to see if anyone knows of people who are taking on this question.

I think question is important because it relates to our “digital dualist” tendency to view the Web as separate from “real life.”

So far, I see three, potentially compatible, explanations:

1. Capitalism’s infinite need for expansion. Couching digital information in a language of space and territory, makes it easily integrated into the existing systems of property ownership and commodification. Digital information is equated to something we already know how to buy and sell: land. It provides a new target for imperialistic ambitions.

2. Simplification, comprehensibility, and individualism. Our current moment in history is defined by the overwhelming need to define oneself as a unique individual and thus free from social or other constraints that would undermine claims of distinctiveness. Nathan Jurgenson recently labeled this “The Urban Outfitters Contradiction: be unique just like everybody else!”’ In such a world, we tend to over-simplify the environment around us in order to exaggerate our own claims agency. Spatial metaphors make the Web seem like something we can (and are even destined to) master. The World Wide Web became the new Wild Wild West—the new home for rugged individualism (in the form of hackers and cyberpunks) and a new site of manifest destiny. This is reflected in early cyber-Utopian rhetoric which was all about self-empowerment.

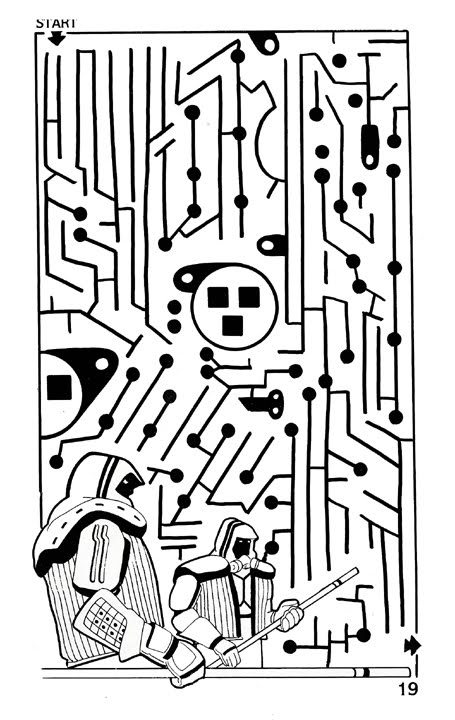

3. Vestigial ideologies. The collective imagination was decades ahead of the empirical reality of the Web. The vocabulary we use—“cyberspace,” “virtual reality,” and “hackers” who get “sucked-in” to the computer—originated in our fantasies of what the Web might one day look like rather than as analytical terms oriented toward actually describing the world we live in. Increasingly, that reality diverges from the fantasies and ideologies that spawned this vocabulary, and we have been slow to adapt and evolve.

Thoughts?

Reach me with a comment here or @pjrey on Twitter.

Comments 40

Greg Lastowka — October 1, 2012

Maybe it's a useful metaphor?

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=306662

http://works.bepress.com/alfred_yen/15/

Sally — October 1, 2012

Maybe "space" is just how we think, or something we have been trained to transfer ideas through. Space is where we are, and what we know.

In the early days of multimedia, when I was at Apple, we designed a project called The Virtual Museum in the 3D graphics group. Produced on a CD-ROM, The Virtual Museum enabled people to "walk though an exhibit space" using QuickTime™ (which was still in Beta) movies that had interactive pixel components. This was all new. We took pains to decide about whether or not a 3D metaphor of replicating space was a good idea and ultimately went with it to test if people needed to orient themselves in space that way, or could do something else. When people visited The Virtual Museum for the first time, they appreciated being able to walk around it. Then they never wanted to navigate that way again and used our alternate navigation. Subsequently, I learned that space metaphors on the computer weren't useful when accessing data, but useful when people wanted to roam around as in WOW and other game environments.

In those early days, we used a spatial metaphor to provide a level of cognitive transition. In 1991, not many people had the Internet, there was no web to speak of and many people didn't have computers in the same ratio as they do now. There wasn't talk of being in "Cyberspace" before the network existed. Once we started connecting to each other, the metaphor changed.

Early MOO's that were text based, had "rooms," like the LAMDA MOO at PARC. This was based on Pavel's house: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LambdaMOO

The thing is, there is something in humans that thinks about things in terms of where we are. Our bodies are in 3 dimensional space. Our minds may or may not be capable of abstract thought, but our person--the body we are attached to is in 3D space and space is the first frame we push stuff through in terms of perception.

That may change as we change, or it may not. I found that non-3D space metaphors worked better for data, but people do like to wander and roam as well, and for the most part that comes from being able to wander and roam in their bodies in the world.

nathanjurgenson — October 1, 2012

to continue with pj's questioning, here are two more:

1 - why are we so much more likely to think of the web in spatial terms (more than text or voice)?

i can think of examples of textual information being constructed as a new, other world (e.g., The Neverending Story), but that's the exception more than the rule. with the Web, we are much more likely to default to spatiality. "on" line and "off" line: the language runs so deep that it is hard to escape digital spatiality.

2 - how might our understandings of the web be different if we didn't default to spatial?

what if we, from the start, understood digital information, like textual or oral, as something coming at us, something we contribute to, in one space? would digital dualism have flourished?

if we never went down the road of the-Web-as-space we would have less difficulty understanding that time spent using digital technologies and meeting face-to-face are not zero sum. right now many people have the dualist-Matrix-like presupposition in their minds...so time spent online is time spent not offline. simple. once we remove the spatial metaphor and replace it as a layer of information augmenting one, single, real space, research findings make more sense. when we find that people who use facebook also meet more face-to-face, that seems entirely possible in a one-reality augmented paradigm. the dualist will have to do some mental gymnastics to make it fit their model. (like the many concentric circles used by geocentric/Ptolemaic astrology to make the evidence of the sky fit their Earth-is-the-center-of-the-universe fallacious presupposition)

Nav — October 1, 2012

I'm not qualified enough to give a good answer to this, but my own project is partly about the connections between the imagination, aesthetics and the digital virtual as each alternate spaces that are 'actually' alternate, but are nonetheless constructed as such. That's one line of inquiry that someone who knows a lot more than me could possibly look into fruitfully.

Descartes' work is shot through with spatial metaphors, so that's what I latched onto as a sort of proto-virtual space. Of course, he was also the progenitor of another form of dualism, so maybe that's signficant.

In terms of aesthetics, a prof of mine just mentioned that there's an argument to made that Aristotle's emphasis on the stage in his aesthetic theory came to dominate how we think of aesthetics. When we read novels, we tend to think of our bodies, the physical book and the imagined, pictured narrative 'floating out there' - which of course, it isn't at all. But it is interesting to think about not only spatial metaphors, but why we initially (at least in the Western tradition) referred to the imagination or aesthetics as fields or spaces unto themselves - or why it was necessary to posit a space that 'exceeded' or 'went beyond' the material. That dialectic - and its quasi-teleological discourse of a linear movement forward toward something - might be another fruitful thing to look at.

There's also just the legacy of screens themselves - of the way pictures emanated from a point forward onto a canvas, which was then contained 'in' a box. I wonder how much TV and the 'mediascape' (again, spatial metaphors) influences that.

Fascinating question, though, isn't it?! I apologize for my amateurish rambling. Look forward to seeing you and others delve into it further.

Amanda Starling Gould — October 1, 2012

Maybe it too stems - or at least gains purchase - from a phenomenological sense of 'going' somewhere or 'being' somewhere? Early fictional iterations (think Gibson's Neuromancer) that came prior to our current interwebs depicted cyberspace as a place to go to, to enter, to disappear within. Perhaps that contributed to our present spatial conception?

Calinlapin — October 2, 2012

I may be of interest to know that Kant (Yeah I'm talking about an old german philosopher) thought that 'space' was not a concept like any other but rather what what makes experience possible.

Applied to the web, and by using digital dualism, I'd say that if Imanuel were still alive he'd probably argue that the spatial metaphor is simply the most effective way to make sense of the web (i.e this other 'world').

Why Do We Use Spatial Metaphors to Talk about the Web? by PJ Rey « anagnori — October 2, 2012

[...] From: Why Do We Use Spatial Metaphors to Talk about the Web? by PJ Rey, The Society Pages, http://thesocie... [...]

Boaz — October 2, 2012

Maybe the half-way legitimate concept of worm-hole from general

relativity was part of it? The web is somehow surprising and

futuristic, and so people could look to science fiction for ideas for

reference. Certainly no worm-holes are involved in sending and processing electro-magnetic signals around the globe, but the idea that space-time may be connected in a more complex way than just Euclidean space could be an orienting metaphor. Space is a pretty flexible mathematical concept also. One could have discrete spaces as well as the smooth manifolds required in general relativity (or normal classical physics). Quantum mechanics is also sometimes drawn from to describe changes in society or aspects of people or communications that haven't been studied in a systematic way.

I guess when one sees something unfamiliar, they may look to something

else unfamiliar, and hope that perhaps its all the same mystery.

As with various uses of Quantum mechanics, physicists are used to it being almost part of their job to point out disanalogies, whenever an analogy is claimed.

Trevor — October 2, 2012

I like Sally's point. I think it is rather natural for us to spatialize the web. If you participate a lot in a particular sub-reddit, or a section of a web forum, it feels like a place where you and one set of folks interact with each other and very quickly you get a sense of there being an "over there" where (different section of the forums or different sub-reddit) where different kinds of folks with a different values and goals hang out. I think a lot of the work on online ethnography/netnography gets at part of why we experience the web as a place and to some extent a space. I tried hashing through some of this in Are Online Communities Places or Artifacts?

Boaz — October 2, 2012

Trever- one can imagine the space involved when one participates in a

forum, and one could do so as well for an email list, but there are

obvious disanalogies as well. What are the surroundings to this

space? Can one move closer together, or further apart within this

space? Within some software environments, these questions could have

answers, but otherwise, its not so obvious why talking about the

website that collates the responses, or the set of documents being

exchanged should be thought of as a space like a physical space. Yes,

its a space, in some sense, but one with very different properties

than a physical space.

Boaz — October 2, 2012

Calinlapin- Yes, Kant thought that Euclidean space was a priori knowledge. General relativity was so revolutionary partly because of this. It was assumed that one could only think in terms of flat Euclidean space. I believe it was the logical positvists (e.g. Carnap, Reichenbach) who went back to Kant's arguments and showed that he was wrong on this point in light of general relativity and non-Euclidean geometry. They discussed how we can learn about space in terms of more basic concepts and find out about the local 3-dimensionality of space. After these kinds of analyses, the structure of space (and time) becomes an empirical question, rather than a priori given.

Anyway, I don't think we need anything so heavy-hitting here. But I do think Kant was wrong on this.

Jeremy Antley — October 2, 2012

There is also the folkloric angle to consider here- the idea of sacred space versus profane space, the natural dichotomy embodied at the root of our perceptual cognition. We are physical creatures, who, from day one, engage with space as the primary sensory input.

I would also add that text has long been used to create other worlds- the rule of law is predicated on this very belief, the idea that community enforced rules cannot be spread over great distances or differing cultural notions. Benedict Anderson's entire 'Imagined Communities' argument hinges on the Newspaper being a homogenizing force for culture and time. Passports, tax registers, census records- all of these take great pains to locate the body in a particular space or conception of space, regardless if the person documented feels aligned with those interests. I would argue text's role in this is not the exception- its the very rule that gives text power over the actions of lived experience. This is why James Scott in his 'Weapons of the Weak' went to great pains to document what he called 'Backstage' speech- a non-textual place where textual or other oral claims could be disputed or refuted.

If you want an example of Phenomenology and the spatial metaphor exemplified, check out Vaclav Havel's 'Power of the Powerless' essay. He argues for 'living in truth' as a way to create a space outside of post-totalitarian control, the primary example being a shopkeeper that refuses to display a party slogan on his storefront window.

Will — October 7, 2012

I was just looking through some highlights from Rifkin's "Empathic Civilization" and was reminded that he noted recent neurological research tying emotions to body mapping. Thinking back to Gibson's original description of cyberspace, it was a very emotional experience -- an ecstatic one that was in many ways more real than the real world. Rifkin gets into this notion of fiction as shared experience (to @jeremy's point), just as cyberspace is a shared experience.

Oliver Sachs has also written some great stuff about how the brain guesses at the shape of the body, which suggests that the brain is primed to think in spatial terms.

Finally, I spent part of last year reading about McLuhan and spatial theory and would note that he stated again and again that common media create _actual_ spaces. So perhaps we're not just applying "real" spatial terms to cyberspace, but actually making new spaces through electronic means (and using the same tried-and-true terminology to describe it).

Pontification aside, I guess in summary agree with @sally -- spatial metaphors are probably inherent in our worldviews (so long as we continue to be embodied, at least!).

Will — October 7, 2012

FYI, great book on McLuhan and spatial theory -- http://www.amazon.com/McLuhan-Space-Geography-Richard-Cavell/dp/0802086586

Will — October 7, 2012

PJ -- to your second point (a great one) -- seems to be a lot of thinking these days about commodification, and also the tendency of capitalist systems to think in terms of "finite" resources (as you note, cyberspace becomes a land grab, a la Second Life). (E.g., Graeber's "Debt.")

Will — October 7, 2012

Final comment, I promise (just excited to see others thinking about this!). Quote from Cavell's book: "The mass media, he [McLuhan] suggests, operate like myth; both 'abridge space and time and single-plane relationships, returning us to the confrontation of multiple relationships at the same moment.'" When you look back at mythopoetic literature, it's almost always realized in terms analogous to the world we sense every day. Why should cyberspace be any different?

Boaz — October 8, 2012

Another possible angle on this question would be to look at real ways

in which internet technologies can replace (or provide alternatives

to) activities that may otherwise take physical space. We may use spatial metaphors as a kind of placeholder for some of the aspects of the activity that may have been lost. For example, we talk about shopping "online" as if it were a place. Going to a bookstore, for example, can be a fun activity in itself. It can be social, with running into friends, or meeting someone new that is interested in similar books. And the bookstore itself does a service of selecting books that can be of interest to the clientelle that go there. So, although Amazon may be efficient and provide benefits over going to a bookstore, there are losses also. Similarly, using a G+ "hangout", may be efficient and provide benefits over getting together in same physical space, but there are losses also (can't share the same food, can't go to the same surrounding spaces together, limited by

camera views, and obviously many, many others).

One could be cynical and assume that the metaphor encourages people to

forget about the losses. The activity has been redefined, with some

of the more obvious aspects covered in metaphorical ways. Or one

could be more positive and see the spatial metaphors as orienting and

inspiring the development of services that enrich it.

For example, I was recently talking about books with a friend, and he said that he saw my physical books as pure "decoration". I can understand that digital books are convenient, and offer lots of benefits, (and I do a lot of reading of websites, as well) but its a little scary to have to take a cherished activity and articulate exactly what about it is valuable, so that when it is recreated in a new form, those aspects will still be there. I think somehow this tension is part of the story of why we put spatial metaphors on so many web based activities.

Will — October 8, 2012

Oh, PJ -- you might also look at Kitchin and Martin's "Code/Space: Software and Everyday Life."

Strong and Mild Digital Dualism » Cyborgology — October 29, 2012

[...] in some zero-sum fashion. As stated above, the augmented perspective rejects the unfortunate spatial language we’ve created and looks at materiality always interpenetrated by information of [...]