At the end of a press conference in January, Microsoft announced HoloLens, its vision for the future of computing.

The device, which Microsoft classifies as an augmented reality (AR) headset, incorporates a compilation of sensors, surround speakers, and a transparent visor to project holograms onto the wearer’s environment, a sensory middle ground between Google Glass and virtual reality (VR) headsets like Oculus Rift. Augmented and virtual reality headsets, like most technology saddled with transforming our world, reframe our expectations in order to sell back to us our present as an aspirational, near-future fantasy. According to Microsoft’s teaser site, HoloLens “blends” the digital and “reality” by “pulling it out of a screen” and placing it “in our world” as “real 3D” holograms. Implicit in this narrative is that experience as mediated with digital screens has not already permeated reality, a possibility the tech industry casts perpetually into the future tense: “where our digital lives would seamlessly connect with real life.”

While technology remains in flux, the presence of a screen endures, even in devices like HoloLens that purport to supplant them. Yet in light of how mobile devices made their predecessors feel anachronistic, futurist speculation anticipates the next big thing that might displace (“disrupt”) screens. Majority opinion has long gravitated around the emergence of a holodeck or matrix, a virtual space indistinguishable from reality, with AR/VR headsets their forerunners. A less common but persuasive theory sees the key to the future in the materialization of data itself. Where pop evolutionary psychology seeks solace in a return to our ancestral roots, this futurism proposes an ostensibly postdigital paradigm, one fit to exploit the natural physiology humans evolved over the course of millennia and therefore unleash humanity’s full creative potential.

Of postdigital futurists, the most outspoken is arguably Bret Victor. Formerly a Human Interface Inventor at Apple and the lead designer of Al Gore’s Our Choice iPad app, Victor has executed designs and argued extensively for the “humane representation of thought,” a framework for digital design premised on “amplify[ing] human capabilities.”

Victor outlined his concerns with digital media in A Brief Rant on the Future of Interaction Design, an essay in response to Microsoft’s earlier future vision. The rant draws distinctions between the tactile qualities of material objects, such as hammers and paper books, and the flat interfaces of screens. Victor’s dissatisfaction with touchscreens is evident, but he ultimately refrained from making specific recommendations, instead gesturing toward the potential of experimental digital interfaces (including holograms) that might one day foster digital media with greater material sensibilities.

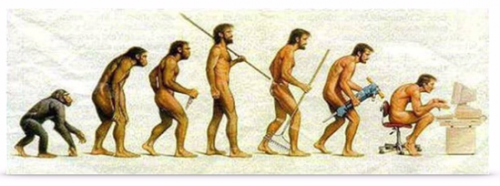

In a 2013 talk, entitled “The Humane Representation of Thought: a trail map for the 21st century,” Victor expands on his earlier hypothesis. The talk opens with a brief summary of the history of knowledge work as Victor sees it, which helps illustrate his view of technology and its place in our lives:

We invented this lifestyle, this way of working, where to do knowledge work meant to sit at a desk and stare at your little tiny rectangle and make little motions with your hand. It started out as sitting at a desk, staring at papers or books, and making little motions with a pen and now it’s sitting at a desk, staring at a computer screen, making little motions on your keyboard. But it’s basically the same thing.

The prevalence of screens, if not all 2D representations of knowledge, seems to stand as a bitter reminder for Victor of how, in spite of the technical and social churn happening around them, the norms of knowledge work as an exclusive occupation have remained mostly static. Following his gloss of knowledge work, Victor concludes:

And this is basically just an accident of history. This is just the way our media technology happened to evolve and then we kind of designed a way of knowledge work for that media that we happened to have.

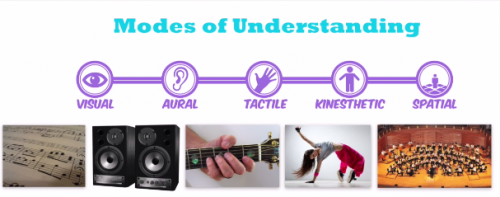

Over the course of his talk, dotted with diagrams and anecdotes inflected by evolutionary axioms, Victor makes the case for a kind of dynamic material, data-driven simulations made “tangible” with the inclusion of “real,” manipulable matter. With availability of this digital material (‘smart sand’ as Wired dubbed it), users could simulate data in a form that occupies physical space, one in which users could experiment and explore stimuli as humans did prior to the invention of computers, typewriters, textbooks, or even symbolic language.

The suggestion that our present technology isn’t up to the task of mining the depths of human ingenuity is not merely convenient speculation for a profession whose industry depends on exponential device sales, it has become a self-justifying ideology pursued and evangelized for its own sake. As innocuous as this pursuit seems, its influence on designers at the upper echelons of dominant tech companies has real consequences for users. According to Victor himself, his guidance directly influenced the design of certain aspects of the iPad and the Apple Watch, products from a company that consistently sets the standard for the rest of the industry.

In deeming real technologies that more closely imitate material interaction, postdigital futurism too often falls prey to fetishism of the “real.” The advent of new technologies, from touchscreens to social media has arguably opened up new and varied ways and contexts in which to interact with the world. Emulating prior invention in design however doesn’t make the artifact more real. If anything, excessive imitation induces an uncanny valley that only gets more eerie the “better” it gets, a facsimile that invites the very social commentary that dismisses digital interaction as a distraction, an inferior substitute for “real life.”

Preceding the HoloLens demo at Microsoft’s event (at 1hr 57m in), the presenter informs the audience, like a magic show emcee: “you’re going to see through Loraine’s eyes. You’re going to see exactly what she’s seeing…”

As the audience observing the trick, we’re meant to take this statement as fact: we see onscreen what she is seeing. To do so however requires us to engage in the conceit that we experience reality more or less the same. Although our lives and experiences share broad commonalities, perception of realty varies based on those experiences, making them subjective and not readily interchangeable. To accept the presenter’s conceit is to indulge in the fantasy that digital technology levels the playing field, a utopian worldview which frequently dismisses differences in skill level, knowledge, and experience and insinuates that digital experience exists in a separate, virtual (“cyber”) space.

Postdigital futurism, like its virtual reality twin, acknowledges the influence of technological meditation on reality, but deflects responsibility for the nature of the mediation away from its designers. For as populist as a technology that dynamically responds to users seems, to label it as more natural, humane, real presumes (a) that designers know what’s best for users and (b) that the experience of one kind of interaction could be universalized. These presumptions not only rank experiences as more or less “real,” they echo the same knowing paternalism that just as often moralizes encroachments on agency, from Facebook’s manipulation of our sociality to the NSA’s mission of total surveillance chartered under the guise of “homeland security.” Just as we should ask, whose homeland, whose security?, we should ask, technological affordances for whom?. Just as we ought to avoid analysis that ranks ‘physical’ experience over its digital corollary, we should question rhetoric that prizes a particular kind of digital interaction over others.

While judgement of augmented and virtual reality headsets will have to wait until their release, if early reports are an indication, interacting with holograms is more conspicuous than tapping on screens. As the Verge’s preview notes, “It’s basically incredible to see these digital things in real space.” Mundane activities that we perform almost unconsciously through screens feel enchanted, otherworldly as holograms superimposed onto the environment. Although the promise and actual experience that these devices might afford deserves evaluation of its own, to insinuate that holograms or some other future ideal might yield a more “real,” “natural” or authentic experience than our already augmented reality resembles less prophecy than the apocryphal projections of their creators, magicians deceived by the allure of believing their own illusions.

As futurists try to extract digital artifacts from the screen, they downplay its existing relationship to humanity as one primarily between our fingers and the screen. If one of the promises of technology is its capacity to act as an extension of our bodies, turning it into matter would place it distinctly outside of the body. As envisioned, this hyper-real augmentation of reality would seemingly constrain the possible desires expressible through it to ones representable as objects. What this vision ignores is how thoroughly we are already entangled with digital technology, its logic burrowed into us, even in moments away from screens; to disentangle us from it and shackle it to material artifacts would not necessarily amplify human ability so much as constrict our complex relationship with and interactions mediated through technology, a quintessential element of being human.

Nathan Ferguson is a recent creative writing graduate who resides in a hologram called the Midwest. You can tweet him @natetehgreat, read his infrequently updated blog or browse his more frequently updated pinboard.

Comments 2

#Briefing: Das Ende der Aprilscherze, Putins Trollarmee, Ello Redesign, Facebook Riff, YouNow #sleepingsquad - Social Media Watchblog — April 3, 2015

[…] von Microsofts Hololens, die uns in eine bessere Realität führen will und dabei übersieht, dass wir längst in einer Augmented Reality leben. […]

Postdigital Apocrypha; Or the Augmented Future is Already Here, Nathan Ferguson | News, Technology and the Individual — April 7, 2015

[…] http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2015/03/31/postdigital-apocrypha-or-the-augmented-future-is-a… […]