One of the aspects of techno-social life that I’ll be looking at closely in my forthcoming book Superconnected: The Internet and Techno-Social Life is the reality of the online experience. To explore this issue in the classroom, I invited Nathan Jurgenson of this blog to tweet “live” with my “Mediated Communication in Society” class, billing him as a special guest speaker tweeter! Here I describe what I did, why I did it, how I did it — and what happened, much of it unexpected, as a result.

I’m a big believer in using social media in the classroom, especially Twitter, as appropriate. Students generally seem to spark to it, entering willingly, even eagerly, into conversations and collaborations that often continue well after class is over. We discuss relevant topics in the timeliest of ways, posting to our class hashtag links to articles and info that we think will interest one another as soon as we come across them, day or night. Outsiders, including authors of course texts, sometimes jump into these convos, allowing us to get to know them and their ideas personally and more expansively. At some point, the time/space/personnel boundaries of the classroom fall away. The “classroom” is always open and class (i.e. learning) can take place at anyone’s desire, whim, or convenience.

My Mediated Communication class (Rutgers University, Fall 2012) has taken this premise even further. Anticipating that my students might be intrigued by his work exploring online and offline “reality” (see, for example, Digital Dualism and Augmentented Reality, The Facebook Eye, and The IRL Fetish), I asked Nathan Jurgenson if he would join our class on Twitter sometime during the semester. I had considered other modes of bringing him to class — in-person guest lecture, via Skype, etc. But, for me, the opportunity to examine the content AND form of a socially mediated reality, simultaneously, in a class predicated on the study of mediated communication, was too rich to pass up.

I proposed that we spend an hour or so live-tweeting with him. The class would be gathered physically in the classroom and he would join in from his own remote location. Afterward, the students and I would review and reflect on the experience fairly thoroughly – our engagement with Nathan and his ideas, our engagement with one another, what we learned, what we didn’t, and why. My goal was to wring as much as possible, intellectually and socially, from the exercise.

With Nathan on board, I planned and structured the event. I scheduled it for the seventh week of the semester; just past midterms — a good time to focus closely on a set of issues already identified as important. In the week prior to the live-tweet session, the students read the articles of Nathan’s linked to above, plus a selection of critiques of “The IRL Fetish” (Nicholas Carr’s The Line Between Online and Offline, Jenna Wortham’s The End of the Online World As We Know It?, L.M. Sacasas’ In Search of the Real, and Alan Jacobs’ What It Means To See The World With An Eye Toward a Facebook Update). Students wrote responses to these articles on our internal course blog and discussion forum. We talked about them in the classroom. Finally, I asked students to narrow their concerns to a single question that they would ask Nathan during the live-tweet session and to a comment or two that they could post to the class hashtag to get the discussion started in the days immediately preceding Nathan’s appearance.

I looked over the students’ questions, making a few suggestions to improve clarity and avoid redundancy, but generally allowing them to ask him whatever they wanted, including about other topics beyond digital dualism and reality. I described how I envisioned the session proceeding: each student (there are 25) would get to ask at least one question of Nathan, which could be the one they’d pre-planned or one that arose organically during the chat. Follow-up questions would be encouraged and students could “jump in” on one another’s conversations with Nathan in traditional Twitter cross-talk fashion.

The weekend before Nathan’s online visit, conversation began to heat up on the hashtag:

https://twitter.com/Jay_Bills25/status/256530508228468736

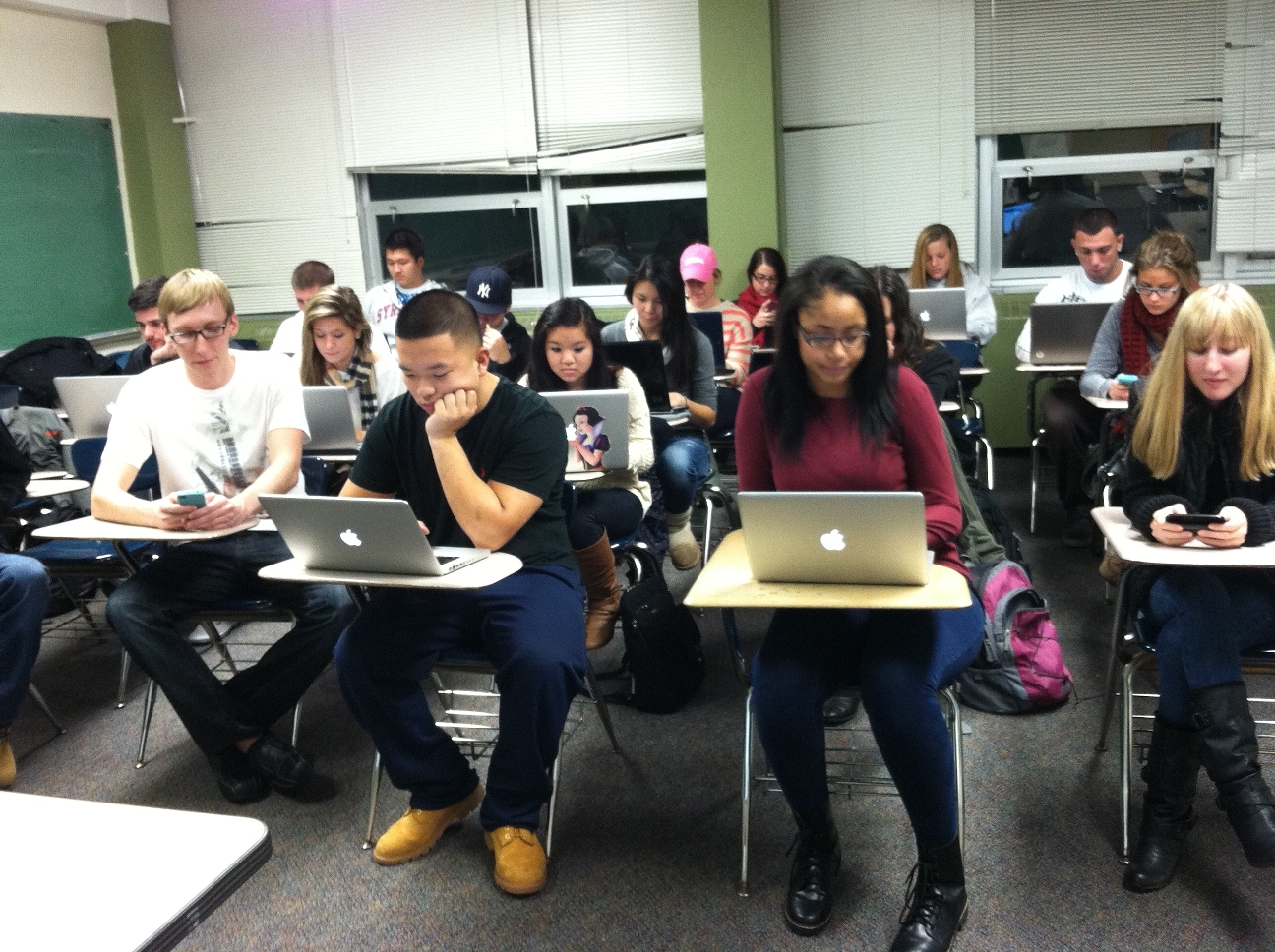

With conversation still humming on the hashtag, the date for the live-tweet arrived. In the classroom, we got ourselves organized. I divided the class into quadrants of six or so students, each of which could take “center stage” with Nathan for about fifteen minutes of the hour. Within each group, students were to ask Nathan questions more or less one at a time, though it didn’t always work out that neatly (and when it didn’t, Nathan handled the barrage with calm fluidity). Students were permitted and encouraged to join whatever active Twitter conversations Nathan was attending to as they wished, but not to carry on separate side convos, which surely would have turned the exercise into a 25-ring circus. All were to stay engaged with Nathan’s current convos and to be prepared to ask him a question when it was their turn.

When Nathan arrived online, the energy in the classroom elevated considerably. Several questions provoked immediate interest, and we were off:

https://twitter.com/RGudovitz/status/258336697417342976

We discussed the augmentation of reality…

…the online self…

https://twitter.com/day_view/status/258334155530702848

…tech addiction…

https://twitter.com/elizabeth_bar/status/258340831331770369

…privacy…

…online dating…

…even how to be a more effective student.

I allowed these Twitter convos to unfold without my participation, figuring that students get more than enough of me during every other class. Instead, I acted mostly as traffic cop, keeping things moving, giving equal time to each quadrant, calling on people when necessary to make sure they got their turn and calling for a halt to new questions when too many were already in the queue. However, about twenty minutes in, something unexpected began to happen.

As the online conversations became deeper, more thought-provoking, and occasionally quite funny, I saw students begin to laugh and talk among themselves about Nathan’s ideas AND about the experience they were taking part in. These were not disruptive conversations, but respectful little sidebars that began to operate as a kind of face-to-face backchannel to the main online event. I had not predicted that something like this would happen — in fact, I had told students that they could bring ear buds to class and listen to music during what I assumed would be the quietest of all class sessions. Yet before long few if any students had their ear buds in. They seemed to want to exchange glances, gestures, and eventually words and laughter, and as they did, so did I. We were communicating both online and face-to-face, with each mode adding something to the other. I couldn’t wait to contact Nathan later to tell him that all this had been going on.

Online community, networks, and participatory culture are major concepts in this course. In this single class session we took a leap toward absorbing and internalizing these ideas and even creating such a culture ourselves. Later, I asked students to reflect on the experience. One or two students shared that they had felt a bit overloaded by the constant rush of information during the session (as I daresay many live guest-tweeters would be), though they persevered impressively and maintained that they were glad that they had taken part in it nonetheless. Nearly all students described a heightened sense of engagement with the material, with one another, and with Nathan, personally, as well. As I usually do, I had the students detail their reflections on the course blog and on the course Twitter hashtag:

https://twitter.com/MaryChayko/status/259121825370484736

One student who couldn’t attend class that day joined in from home, and discovered that

And another of our course’s authors, Evan Selinger, peeked in on the proceedings, tweeted about them, and returned to our hashtag to interact with us later in the semester:

Though the class’s sense of engagement, of learning, was palpable, I should note some important caveats. Even if I had sufficient guest-tweeters to call upon, I would not do this often during any given semester. It requires substantial course time and resources to set up, plan, run, and debrief, and I think the exercise would lose its punch and power if done too often. I also do not think this session would have worked as well with a less dextrous and personable guest-tweeter, with less provocative ideas being exchanged, and with a class that was not “into” Twitter.

I always survey each of my classes at the start to determine the level of interest and willingness of the students to use social media for class-related activities. I offer students an opportunity to opt out of social media use, to use pseudonyms online, and I require those that wish to use it to abide by a strict set of social media use policies which we discuss at great length (and which I am happy to share). I also teach all my students, ad infinitum, ad nauseum I’m sure, to use social media responsibly and professionally. In this particular class, every single student indicated from the start a willingness to use social media in the classroom, including Twitter, in new and creative ways, and to learn unfamiliar social media platforms, such as Storify, for class projects. This freed me up to imagine how to best and most productively use these media without having to worry about leaving a student behind. I’m not sure I would have proceeded with this exercise had I not had such an interested and proficient group – and, of course, such an interesting and proficient special guest-tweeter, for whom doing this had to be a challenge, but who was 100% “game”:

I think we all experienced a little #vertigo during and after our live-tweet class session with Nathan Jurgenson, but I like to think it was well worth it. The students got all kinds of insights into critical course themes and concepts, formed connections with one another and with an early-career professional who was giving them real insight into the ways that they live, and gained a truly “hands on” perspective on mediated communication.They understood that they were participating in and helping to develop a brand new way of learning, too, and to a person they seemed to think that that was pretty cool:

https://twitter.com/ibbyAde/status/260857238728605697

https://twitter.com/day_view/status/259070718032113664

But my favorite outcome was the way the face-to-face “backchannel,” and the class as a community, began, during this event, to coalesce. I can even pinpoint the moment it happened: It was when Nathan responded to a query about how he was handling the barrage of questions:

We laughed loudly in the classroom then, in collective acknowledgement both of Nathan’s wit and the ambitiousness of the learning event that we were engaged in, and creating, together.

Mary Chayko (marychayko.com) is Professor and Chairperson of Sociology at the College of Saint Elizabeth in NJ and a lecturer in Communication for Rutgers University. She is the author of the social science bestseller Portable Communities: The Social Dynamics of Online and Mobile Connectedness and Connecting: How We Form Social Bonds and Communities in the Internet Age, both with SUNY Press, and thinks she’d be able to handle guest live-tweeting almost as well as Nathan Jurgenson. She is on Twitter @MaryChayko and email at mchayko@cse.edu.

Comments 7

Friday Roundup: November 30, 2012 » The Editors' Desk — November 30, 2012

[...] Guest author Mary Chayko, author of Superconnected, invites Cyborgology cyborg Nathan Jurgenson to guest-tweet her class, Doug Hill looks at capitalism through Hollywood films, Jenny Davis writes that it might [...]

Schulgespräche mit Expertinnen und Experten via Twitter | Schule und Social Media — December 2, 2012

[...] Vorteile. Ich beziehe mich auf die Beschreibung eines Kommunikationskurses der Rutger University, wo ein Live-Gespräch mit Nathan Jurgenson, einem der interessantesten Theoretiker von Social Media (vgl. seine Gedanken zu digitalem Dualismus), durchgeführt wurde. Die verantwortliche [...]

Live-Tweeting in the Classroom… - The Society Pages | Holy Hashtags! | Scoop.it — December 3, 2012

[...] To explore this issue in the classroom, I invited Nathan Jurgenson of this blog to tweet “live” with my “Mediated Communication in Society” class, billing him as a special guest speaker tweeter! Here I describe what I did, why I did it, how ... [...]

Mary Chayko — December 5, 2012

I've had several requests for my social media policy referenced in this story. Here it is:

Dr. Chayko’s Social Media Policy For Classroom Use

There are many outlets available to you to communicate with current and future friends and acquaintances as well as family members. Social networking sites (e.g., Facebook, MySpace, Twitter), chat rooms, bulletin boards and blogs are just a few of these outlets. I understand the importance and usefulness of these outlets and encourage responsible use of them. Whether face-to-face or in cyberspace, you represent yourself, your family, and your University when you engage in social media, and it is expected that you to do it with the highest standards of honesty, integrity and class. You are expected to follow the following guidelines as you participate in any of the above-mentioned or similar communications in conjunction with my class:

• It is recommended that you keep your page/site private or anonymous, but understand that anything you post online (even if you make your site private) is out of your control the moment you place it online and is available to anyone in the world.

• Do not post your home address, local address, phone numbers, date of birth, class schedule, etc. If you do, you open yourself up for predators, stalkers, identity thieves, and other criminals.

• Do not post, email, text or otherwise electronically share information, photos, videos, or other representations of sexual content, inappropriate behavior (e.g., actual or implied drug or alcohol use), or items that could be interpreted as demeaning or inflammatory. You are also responsible for all information posted by others on your site. Be professional, and encourage others to do the same.

• Do not post information, photos, videos, or other items online that could embarrass you, your family, or the University. This includes information, photos and items that may be posted by others on your page/site.

• Many potential employers and graduate schools analyze these sites in their search processes. Anything posted that is attributed to you could be damaging to your future.

BEST PRACTICES AND REMINDERS:

• Think twice before posting, tweeting, texting, or sending an email -- every single time. If you wouldn't want your teacher, parents, or future employers to see it, don't send it.

• Be respectful and positive online.

• Remember, many different audiences may view and/or monitor your information online including children, law enforcement, your family, faculty, college administration, etc. Consider the impact of your social media use on members of any potential audiences.

• Be aware of posts, photos, and videos in which you appear on others’ sites. Block or do not permit the posting or sharing of anything in which you appear that would constitute a violation of this policy.

• Remember that a permanent record of all that you do is left when you use the internet, even when you keep your page private (which you should do). Understand and use the privacy/security settings made available on these sites. Remember that even if you delete something, it's still out there. Be in a clear, thoughtful state of mind when you communicate electronically. Do not text, IM, email or post when you are not thinking clearly and responsibly.

You will always have the option to opt out of social media use in this class and to be provided with an alternative method for doing all relevant work and completing all assignments.

Adapted from and in conjunction with Rutgers University Student-Athlete Social Media Policy and Rutgers Women’s Soccer Social Media Policy.

Lauren — December 5, 2012

I'm proud to be a part of this live-tweeting class experiment! Even more excited about being included in this story. Loved the experience. Many thanks to Nathan and Dr. Chayko for making it happen!

Frances — December 6, 2012

It's such an amazing feeling to be a part of this new augmented teaching experience! Many thanks to Dr. Chayko for her creativity and Nathan for chiming into our class to educate us on Augmented reality! #Com432 we are so LEGENDARY!

Still Thinking About Now: On Twitter and (Real) Time | Writing Through the Fog — December 9, 2012

[...] Earlier this week, the students sent me tweets over the course of a few days, using the hashtag #com432. I replied at a leisurely pace throughout the first day, but at one point later that evening, a more concentrated stream of tweets came in at once, and I interacted with a number of students in real time for a short while. (Earlier in the semester, the class engaged in a more structured live-tweet session with Cyborgology editor Nathan Jurgenson.) [...]