Hipsters have been much discussed on the Cyborgology blog (see: here, here, here, and here). Cyborgology authors have also talked about the fetishization of low-tech/analog media and devices (see: here and here). As David Paul Strohecker pointed out, these two issue interrelated: “hipsters are at the forefront of movements of nostalgic revivalism.” I want to pick up these threads and add a small observation.

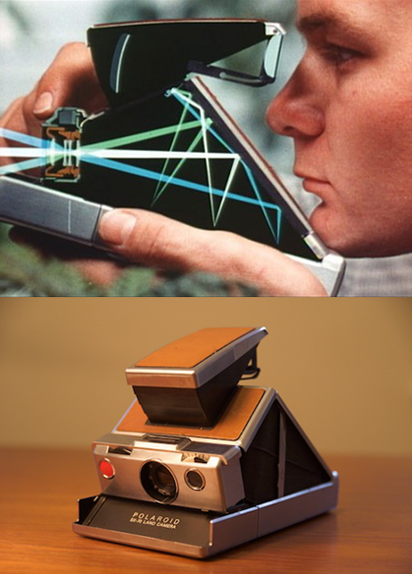

Nathan Jurgenson and I were discussing why low-tech devices have a seductive quality. Consider the popularity of, for example, fixed-gear bicycles or vintage cameras (such as the Kodak Brownie or the Polaroid PX-70 [correction: SX-70]). Though I think this phenomenon is probably overdetermined (in the Freudian sense of having multiple sufficient causes), I came up with a theory that seems worth further consideration: namely, that hipsters’ obsession with antique devices reflects a desire to escape the complex and highly-interdependent socio-technical systems that characterize contemporary society and return to time in which technology appeared to be something that humans could master and, thus, use to affirm their individual agency. In short, the fetishization of low-tech is about the illusion of agency; it provides affirmation for the hipster whose identity is defined by the post-Modern imperative to be an individual, to be unique.

Žižek is often cited as the philosopher of the hipster or the hipster philosopher, but, here, I argue that Simmel and Deleuze were the true Oracles of Hipsterdom. Simmel observed that the individual was a Modern phenomenon–that the desire to “be different” is historically contingent. Delueze identified this desire to be unique as something rather insidious, when he described that the mechanisms of social control are being decentralized away from institutions such as prisons, schools, and hospitals and are now situated within the mass population itself. We, each and all of us, are now the primary mechanisms of social control. We are built to desire what society needs from us and to demand the same from others. Delueze observes with transparent contempt that “young people strangely boast of being ‘motivated;'” they require no institutional coercion.

Žižek is often cited as the philosopher of the hipster or the hipster philosopher, but, here, I argue that Simmel and Deleuze were the true Oracles of Hipsterdom. Simmel observed that the individual was a Modern phenomenon–that the desire to “be different” is historically contingent. Delueze identified this desire to be unique as something rather insidious, when he described that the mechanisms of social control are being decentralized away from institutions such as prisons, schools, and hospitals and are now situated within the mass population itself. We, each and all of us, are now the primary mechanisms of social control. We are built to desire what society needs from us and to demand the same from others. Delueze observes with transparent contempt that “young people strangely boast of being ‘motivated;'” they require no institutional coercion.

This shift in the nature of social control is of monumental importance (as Virno, Negri, and others have described) because top-down institutions promote conformity and homogeneity (at least, within various social classes), which is appropriate for assembly line workers or retail clerks; however, in a new economic paradigm defined by the activity of software engineers, graphic designers, and the like, conformity is anathema to the goal of mass innovation. That is to say, institutional control is counter-productive to a (post-Fordist) economy of ideas and innovation and, thus, must be replaced with a new system of self-regulation reinforced by mass surveillance. As institutions weaken, individuality and uniqueness are no longer stifled but, instead, are promoted as the chief values of hipster culture. Innovation is the result of constant surveillance of and comparison to other individuals.

So, hipsters are the product of a moment in history where the socio-economic system benefits from and has discovered effective methods to enforce the moral imperative to “be unique.” The hipster aesthetic reflects an ideology of hyper-individualism, though this individualism is itself paradoxical because it is socially mandated.

How does this relate to technology then? As, I have argued in the past, citing Anthony Giddens’ “bargain of modernity,” the complexity of modern technology and the expert system required to produce and operate it threaten our sense of individual agency by continually reinforcing our dependency on others (this experience of being just another component of a technologic system and not the master of a tool or device is similarly captured in Jacques Ellul’s notion on”technological autonomy” and actor-network theory as derived from Bruno Latour). The structural reality of Modernity’s complex socio-technicals systems is at odds with the individualistic ideology uniqueness.

Thus, nostalgia for the low-tech/lo-fi/analog is really nostalgia for a time when technology could be mastered–a time when you could fix your own car or bike, a time when you pop open the back of a camera and intuitively understand how it works, a time when you knew where your food came from and how it was prepared, a time when the circuits in electronic were large enough to be visible and an average person could figure out how to repair, replace, hack, and even build them, a time when a device was yours to open and when warranties end-user agreement didn’t micro-manage how used your own property. In short, the appeal of low-tech is it affirms our sense of independence and individuality.

Low-tech is also about a form of authenticity. As technology has grown more complex, manufacturers have tended to mask it with layers of design. William Gibson noted in “The Gernsback Continuum,” that

The Thirties had seen the first generation of American industrial designers; until the Thirties, all pencil sharpeners had looked like pencil sharpeners your basic Victorian mechanism, perhaps with a curlicue of decorative trim. After the advent of the designers, some pencil sharpeners looked as though they’d been put together in wind tunnels. For the most part, the change was only skin-deep; under the streamlined chrome shell, you’d find the same Victorian mechanism.

Perhaps the quintessential example is the marketing of the iPod/iPhone/iPad which asks you to forget altogether the technical specifications of the product and instead immerse yourself fully in the magic of the design. As Nathan noted in our conversation, this is analogous to Marx’s concept of fetishization, where the set of human and technological relations required to produce a thing are concealed and the thing becomes defined only by its superficial characteristics. The hipster low-tech movement seeks to dispel this illusion, by returning to things that can be easily understood and laid bare.

The hipster low-tech fantasy–“the dream of the 1890s“–is one of escape from the complex socio-technical systems that we are highly dependent on but have little control over. It is a fantasy of achieving the most radical expression of individual agency: the opt-out.

Follow @pjrey on Twitter.

Clarification: I don’t think we are driven, directly, by a desire to master technology so much as the desire to individuate and to be unique. We desire technological simplicity, whether real or illusory (as in the case of Apple), because we feel like we have greater control and agency with respect to simple technology than we do with respect to complex, highly-interdependent technical systems, so that simple technologies better serve this kind of identity work.

Comments 38

Doug Hill — September 27, 2012

PJ,

Wow. A superb essay. I found myself nodding in agreement all the way through. I have to go back and catch up Cyborgology's previous essays on this subject, so I'm not up to date on the discussion. Thus although I want to respond to the present essay, I realize that in the context of the full discussion my points may be off-base or superfluous. Apologies if that's so.

Two points come to mind:

1) It's odd how the meaning of the word "hipster" has been turned inside out. It used to convey someone on the cutting edge, yet as you describe here, accurately I think, the word now has come to mean the opposite: someone who consciously and defensively flees the cutting edge. It used to be hip to be a hipster. Now it isn't.

2) I'd love to see another essay (if you there isn't one already in the archive) that addresses the subtext of your essay, or what I perhaps defensively sense is its subtext, that there is something wrong or pitiable about the characteristics you describe. Your use of words such as "fantasy" and "escape" give that impression. It may be, too, that I'm reacting to the pejorative sense that's attached itself to the word hipster, as mentioned above. In any event I sense you're generally disapproving of the hipster response. Am I mistaken?

I ask this because I wonder if it isn't possible to see the hipster's withdrawal, at least in part, as a form of legitimate resistance. After all, some of the reasons you cite for hipsters' withdraw from modernity – lack of agency, lack of authenticity, lack of identity – seem quite reasonable.

For example, you mention Simmel. I'm certain you've read more of his work than I have, but I remember reading an essay of his where he talked about the “blasé attitude” he saw in city dwellers trying to cope with the over-stimulation and anonymity of metropolitan life. A new sort of perception resulted, he said, from an "intensification of nervous stimulation which results from the swift and uninterrupted change of outer and inner stimuli." This was in the early twentieth century. At this point it's possible to see that blasé attitude as having evolved (mutated) into a sort of rampant disconnection.

I realize that the anonymity of modern urban life has its benefits (freedom from traditional forms of social restraint being the most obvious), and I take the point that rampant uniqueness is also a problem. Both, however, add up to a loss of community that, to me, constitutes a truly regrettable loss. And I refer here to the old-fashioned embodied community. This is another place where I qualify as a digital dualist: I don't think online community and front porch community are equivalent.

Similarly, as Ellul pointed out, any promise of individuality offered by the mass-marketing mechanisms of the technological society is a lie, an advertising slogan and nothing more. That's another place where resistance seems worthwhile. (See my essay on Ellul's ideas on technique as applied to Occupy Wall Street, http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2011/12/07/6515/)

In short, the withdrawal of the hipsters can be seen as reaching *for* something rather than backing away from something. For that reason I've always thought it a shame that the Republicans have co-opted the word "conservative." There are some things worth keeping, after all, the planet among them. Is the alternative to simply let go and ride cheerfully over the waterfall of modernity?

Again, apologies for coming late to the discussion, and thank you for an excellent essay.

Christen — September 27, 2012

I enjoyed the look at this return to simplicity. I definitely agree with you that people want to understand the things that surround them, and when technology gets complicated to the point where it seems to be magic, some people will opt for a simpler, more old-fashioned version. (like when my computer had motherboard failure, and I wished I could write my papers with a fountain pen) Thanks for posting.

Hipstertechnoauthenticity » Cyborgology — September 27, 2012

[...] Rey just posted a terrific reflection on hipsters and low-tech on this blog, and I just want to briefly respond, prod and disagree. This [...]

SAA — September 27, 2012

Great essay, P.J.

You wrote: "I came up with a theory that seems worth further consideration: namely, that hipsters’ obsession with antique devices reflects a desire to escape the complex and highly-interdependent socio-technical systems that characterize contemporary society and return to time in which technology appeared to be something that humans could master and, thus, use to affirm their individual agency."

This is unfortunately not a new theory and has already been said about lots of groups--particularly Steampunks.

Jason Downey — September 27, 2012

I don't have much to say other than it was an interesting observation, and that I really enjoyed the way you phrased your summation: "It is a fantasy of achieving the most radical expression of individual agency: the opt-out."

I'd love to be able to invite you to Japan for a season or two, to loose your eyes on the trends over here.

New Myspace: Bringing (Re)Gentrification Back? » Cyborgology — September 28, 2012

[...] alongside a reference to ‘hipsters’, it is almost always meant in the negative sense. (It’s Hipster Day here at [...]

Hipsters and Low-Tech » Cyborgology | Feed | Scoop.it — October 1, 2012

[...] hipsters’ obsession with antique devices reflects a desire to escape the complex and highly-interdependent socio-technical systems that characterize contemporary society and return to time in which technology appeared to be something that humans could master and, thus, use to affirm their individual agency. In short, the fetishization of low-tech is about the illusion of agency; it provides affirmation for the hipster whose identity is defined by the post-Modern imperative to be an individual, to be unique. [...]

nathanjurgenson — October 1, 2012

i wrote a response to this post here: http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2012/09/27/hipstertechnoauthenticity/

john — October 3, 2012

I dont know, every hipster has a smart phone

Low-tech Practices and Identity « The Frailest Thing — October 5, 2012

[...] what do we make of the interplay among these three phenomena? In two recent posts at Cyborgology, P. J. Rey and Nathan Jurgenson addressed this question in an exchange of overlapping perspectives with [...]

James Morgan — October 6, 2012

I like this article, but I wish that you could written it without bringing up fixed gear bikes, Portlandia, and the word "hipster".

As somebody who still uses many analog/low-tech processes and has "opted-out" of Facebook/Twitter/Tumblr, it seems to me like the sensibility of this article and the many others like it is one of the main reasons that so many people find the argument itself so easy to dismiss.

Instapundit » Blog Archive » WHY DO HIPSTERS LOVE out-of-date technology?… — October 7, 2012

[...] WHY DO HIPSTERS LOVE out-of-date technology? [...]

Blacque Jacques Shellacque — October 7, 2012

It's not PX-70, it's SX-70.

I remember because had one of them, the one with the sonar focusing.

Daily Pundit — October 7, 2012

[...] on October 7, 2012 1:41 pm by Bill Quick Hipsters and Low-Tech » Cyborgology Thus, nostalgia for the low-tech/lo-fi/analog is really nostalgia for a time when technology could [...]

lakwh4t9gt8fv — October 7, 2012

Part of it is clowning around. One of my collogues at work put a rabbit ears tv antenna on his CRT. It looked hilarious.

Another part of it is to show you are independent of the mainstream herd mentality, that you can recognize utility where you find it and make do with less and still have a full life. You demonstrate a greater skill and intellect if you can do just as well with weaker technology. For example taking photos with a cheap camera that are better than the photographs of someone with an expensive camera because your artistic sense it what matters.

Ronnie Schreiber — October 7, 2012

I'm not a hipster, I'm 57 years old. I do, however, think that there's nothing wrong with using old tech if it works. Old tube stereos sound great. The 50 year old circular saw my father used still works fine for me. I sometimes worry that the move to digital from chemical photography will mean a loss of some art and technique. I do a lot of cycling, but I think folks who ride fixies are stupid poseurs. A bicycle with a coaster hub and brakes is a far more practical and safe vehicle. My bike has derailleurs, caliper brakes and a pretty high tech titanium frame.

I suppose my point is that there's nothing wrong with using technology appropriately and there's nothing wrong with appreciating earlier tech, which after all is the foundation of current tech. In many ways, though, current tech is better. It's easier to use and it does a better job.

Perhaps hipsters think that the wonder of Polaroid cameras was watching the picture devlop before your eyes. No, the wonder of Polaroid was that you didn't have to wait a week before you saw your photos.

I've been spending some time digitizing the home movies and 35mm slides that my dad took as we were growing up and I'm struck by just how primitive the tech was. When I scan a 35mm slide, with photo editing software I can make it look better than it's ever looked.

I shoot a lot of 3D for my web site, Cars In Depth. While 3D photography is almost as old as photography itself, and a century ago the Keystone View company sold millions of stereograms, computers and digital photography make it much easier for people to create their own 3D photos and video.

Those 8mm home movies that my dad shot cost him a few dollars for the film. Add another payment for processing. Wait a week or so before you can even see how what you shot came out. Oh, and the movie you shot was only about 3 minutes long and the only audio was the sound of the projector, which you had to thread properly and fiddle with for ideal results.

My 3d video rig is rudimentary, based on a couple of Kodak (another old tech company that may not survive because they didn't exploit the promise of new tech they'd invented themselves) pocket camcorders. For about what my dad paid for one 3 minute reel of film, I can buy a memory card that will hold about 2 hours of live video. Instead of a tiny 8mm image with grainy film, I can record in HD and even at 60 fps so I can shoot sports and other speedy action. Things are rarely overexposed or underexposed. Plus I can watch it right away.

The good old days were not always good. Children died of ear infections. One in four kids died of a childhood disease. You left your home town to find your fortune and quite possibly never spoke to your parents again. Life was short and brutal for most folks.

I read and write a bit about automotive history. With the possible exception of Henry Ford, who thought that the Model T was perfect, everybody that invented anything during the age of invention in the late 19th and early 20th century tried to improve it. If the people who made old tech didn't think it was good enough, why should we?

Psst: Want to Buy a Morgan 3 Wheeler? | Daily Street — October 10, 2012

[...] four wheels, that smile likely becomes a wide grin. Maybe it’s the influence of steampunks or hipsters, two subcultures that profess a love for old tech as they search for authenticity (or status [...]

bookmarks, issue 29 | my name is not matt — October 11, 2012

[...] Hipsters and Low-Tech — PJ Rey [...]

Hipsters and Low-Tech | Nuance news — November 12, 2012

[...] fULL aRTICLE [...]

The Cost of Opting Out » Cyborgology — November 21, 2012

[...] mailing addresses do you have? I have very few. The selection and embracing of low-tech, as PJ Rey has written, helps us feel like we are in control of technology. He concludes, “It is a fantasy of [...]

Convergence and Obsessions with Obsoletion | We Will Defy — April 11, 2013

[...] This article by PJ Rey hits the nail on the head pretty squarely. The piece proceeds to focus on: [...]

Menneisyysshokki | Medeia — October 11, 2013

[...] tulee tärkein päämäärä. Identiteetin rakennusainekset haetaan menneestä, joka on ”merkityksellistä” ja hallittavaa toisin kuin kaoottinen nykyisyys, joka vaatii jatkuvaa tulkintaa ja ymmärtämistä. Tulevaisuuteen [...]

Je retrofetiš reakcí na rychlý technologický vývoj? | honzapav.czhonzapav.cz — January 26, 2014

[…] A zkuste vyjet na horáku do města. Budete za blbce, protože dnes letí favorit. A ani přehazovačka už není trendy (alespoň ta cyklistická, protože na hlavě hipstera ji možná uvidíte). Musíte mít furtošlap (fixku či fixgear) nebo alespoň single-speed. I já si jeden takový u funbikes nechal postavit. Do módy se kromě starých kol často vrací mnoho jednoduchých prvků z dob dřívějších a vypadá to, že se casual uniforem z kyberpunkových povídek zřejmě nedočkáme. A své má za sebou i IKEA, protože její cílovka – ti mladí, kteří nemají peníze na pořádný nábytek, si jej dnes stloukají s Lubošem v Paletkách. Když už se bavíme o DIY (do it yourself), asi by nebylo vhodné zapomenout na Arduino. Arduino je takový malý počítač, který slouží k levnému a rychlému vyrobení prototypů (ještě se o tom zmíním v samostatném článku). Je na něj možné připojit mnoho různých senzorů (zvuk, pohyb, světlo, …) a na základě přijatých dat pak vykoná nějakou naprogramovanou funkci. A je to jednuduché – místo, abyste utíkali do OBI a koupili si samozavlažovací systém, uděláte si ho sami doma. Návodů je spousta. Snažil jsem se popsat pár rozjetých trendů, které směřují spíše jednoduchosti než přílišné komplexitě, kterou nejsme schopni ovládat. Možná jde o návrat do minulosti, kdy jste s každou prkotinou nemuseli do autorizovaného servisu. Přemýšlím už delší dobu o tom, zda je inklinace k jednoduššímu reakcí na velmi rychlý vývoj technologií. Podle P.J. Raye ale nejde o potřebu ovládat technologie, ale potřebu být unikátní, jak píše ve svém článku Hispters and Low-tech: […]

NES Kept Alive by Social Media - Sound On Sight — April 14, 2014

[…] romantics, and other atavists aren’t overly concerned about convenience and portability. They revel in the idiosyncrasies and nostalgic charm of dated technology. They want bulky, cumbersome interfaces to engage with – things that take up space and […]

7 stories to read this weekend — Tech News and Analysis — May 10, 2014

[…] Why do hipsters love low-tech? This piece has the answer. […]

7 stories to read this weekend | Technology — May 10, 2014

[…] Why do hipsters love low-tech? This piece has the answer. […]

7 stories to read this weekend — May 10, 2014

[…] Why do hipsters love low-tech? This piece has the answer. […]

Global Tech Review | 7 stories to read this weekend — May 11, 2014

[…] Why do hipsters love low-tech? This piece has the answer. […]

We Love the Internet 2014/20: The Unexplainable stock photos edition | Curiously Persistent — May 16, 2014

[…] Hipsters and low tech – the fantasy of opting out […]

7 tales to learn this weekend | Daily News — May 21, 2014

[…] Why do hipsters love low-tech? This piece has the answer. […]

Why you want your old iPod back. And that typewriter. And an Etch A Sketch. And… – Jumbosky Money — September 26, 2014

[…] doing it to subvert the idea of bourgeois display-case values. The fascination with old technology is a well-documented trope of hipster style, signaling authenticity, hilarity and, of course, bloody-minded perversity, but there are more […]

Today UK | Reading, UK | , UK — September 26, 2014

[…] doing it to subvert the idea of bourgeois display-case values. The fascination with old technology is a well-documented trope of hipster style, signaling authenticity, hilarity and, of course, bloody-minded perversity, but there are more […]