In Part I this essay, I considered the fact that we are always connected to digital social technologies, whether we are connecting through them or not. Because many companies collect what I call second-hand data (data about people other than those from whom the data is collected), whether we leave digital traces is not a decision we can make autonomously. The end result is that we cannot escape being connected to digital social technologies anymore than we can escape society itself.

In Part II, I examined two prevailing privacy discourses to show that, although our connections to digital social technology are out of our hands, we still conceptualize privacy as a matter of individual choice and control. Clinging to the myth of individual autonomy, however, leads us to think about privacy in ways that mask both structural inequalities and larger issues of power.

In this third and final installment, I consider one of the many impacts that follow from being inescapably connected in a society that still masks issues of power and inequality through conceptualizations of ‘privacy’ as an individual choice. I argue that the reality of inescapable connection and the impossible demands of prevailing privacy discourses have together resulted in what I term documentary consciousness, or the abstracted and internalized reproduction of others’ documentary vision. Documentary consciousness demands impossible disciplinary projects, and as such brings with it a gnawing disquietude; it is not uniformly distributed, but rests most heavily on those for whom (in the words of Foucault) “visibility is a trap.” I close by calling for new ways of thinking about both privacy and autonomy that more accurately reflect the ways power and identity intersect in augmented societies.

The Impact of Documentary Consciousness

Just before the turn of the 19th century, Jeremy Bentham designed a prison he called the Panopticon. The idea behind the prison’s circular structure was simple: a guard in a central tower could see into any of the prisoners’ cells at any given time, but no prisoner could ever see into the tower. The prisoners would therefore be subordinated by this asymmetrical gaze: because they would always know that they could be watched, but would never know if they were being watched, the prisoners would be forced to act at all times as if they were being watched, whether they were being watched or not. In contemporary parlance, Bentham’s Panopticon basically sought to crowd-source the labor of monitoring prisoners to the prisoners themselves.

Though Bentham’s Panopticon itself was never built, Michel Foucault used Bentham’s design to build his own concept of panopticism. For Foucault, the Panopticon represents not power wielded by particular individuals through brute force, but power abstracted to the subtle and ideal form of a power relation. The Panopticon itself is a mechanism not just of power, but of disciplinary power; this kind of power works in prisons, in other types of institutions, and in modern societies generally because citizens and prisoners alike, aware at all times that they could be under surveillance, internalize the panoptic gaze and reproduce the watcher/watched relation within themselves by closely monitoring and controlling their own conduct. Discipline (and other technologies of power) therefore produce docile bodies, as individuals self-regulate by acting on their own minds, bodies, and conduct through technologies of the self.

Foucault famously held that “visibility is a trap”; were he alive today, it is unlikely Foucault would be on board with radical transparency. Accordingly, it has become well-worn analytic territory to critique social media and digital social technologies by linking to Foucault’s panoptic surveillance. As early as 1990, Mark Poster argued that databases of digitalized information constituted what he termed the “Superpanopticon.” Since then, others have pointed out that “[even] minutiae can create the Superpanopticon”—and it would be difficult to argue that social media websites don’t help to circulate a lot of minutiae.

Facebook itself has been likened to a digital panopticon since at least 2007, though there are issues both with some of these critiques and with responses to them. The “Facebook=Panopticon” theme emerges anew each time the site redesigns its privacy settings—for instance, following the launch of so-called “frictionless sharing”—or, in more recent Facebook-speak, every time the site redesigns its “visibility settings.” Others express skepticism, however, as to whether the social media site is really what I jokingly like to call “the Panoptibook”; they claim that Facebook’s goal is supposedly “not to discipline us,” but to coerce us into reckless sharing (though I would argue that the latter is merely an instance of the former).

Others point to the fact that using Facebook is still “largely voluntary”; therefore, it cannot be the Panopticon. ‘Voluntary,’ however, is predicated on the notion of free choice, and as I argued in Part I, our choices here are constrained; at best, each of us can only choose whether or not to interact with Facebook (or other digital social technologies) directly. Infinitely expanding definitions of ‘disclosure’ notwithstanding, whether we leave digital traces on Facebook depends not just on the choices we make as individuals, but on the choices made by people to whom we are connected in any way. For most of us, this means that leaving traces on Facebook is largely inevitable, whether “voluntary” or not.

What may not be as readily apparent is that whether or not we interact with the site directly, Facebook and other social media sites also leave traces on us. Nathan Jurgenson (@nathanjurgenson) describes “documentary vision” as an augmented version of the photographer’s ‘camera eye,’ one through which the infinite opportunity for self-documentation afforded by social media leads us not only to view the world in terms of its documentary potential, but also to experience our own present “as always a future past.” In this way, “the logic of Facebook” affects us most profoundly not when we are using Facebook, but when we are doing nearly anything else. Away from our screens, the experiences we choose and the ways we experience them are inexorably colored not only by the ways we imagine they could be read by others in artifact form, but by the range of idealized documentary artifacts we imagine we could create from them. We see and shape our moments based on the stories we might tell about them, on the future histories they could become.

I argue here, however, that Facebook’s phenomenological impact is not limited to opportunities for self-documentation. More and more, we are attuned not only to possibilities of documenting, but also to possibilities of being documented. As I explored in Part I of this essay, living in an augmented world means that we are always connected to digital social technologies (whether we are connecting to them or not). As I elaborated in last month’s Part II, the Shame On You paradigm reminds us that virtually any moment can be a future past disclosure; we also know that social media and digital social technologies are structured by the Look At Me paradigm, which insists that “any data that can be shared, WILL be shared.” Consequently, if augmented reality has seen the emergence of a new kind of ‘camera eye’, it has seen as well the emergence of a new kind of camera shyness. Much as Bentham designed the Panopticon to crowd-source the disciplinary work of prison guards, Facebook’s design ends up crowd-sourcing the disciplinary functions of the paparazzi.

Accordingly, I extend Jurgenson’s concept of documentary vision—through which we are simultaneously documenting subjects and documented objects, perpetually aware of each moment’s documentary potential—into what I term documentary consciousness, or the perpetual awareness that, at each moment, we are potentially the documented objects of others. I want to be clear that it is not Facebook itself that is “the Panoptibook”; knowing something about nearly everyone is not nearly the same thing as seeing everything about anyone. Moreover, what Facebook ‘knows’ comes not only from what it ‘sees’ of our actions online, but also from the online and offline actions of our family members, friends, and acquaintances. Our loved ones—and our “liked” ones, and untold scores of strangers—are at least as much the guard in the Panopticon tower as is Facebook itself, if not moreso. As a result, we are now subjected to a second-order asymmetrical gaze: we can never know with certainty whether we are within the field of someone else’s documentary vision, and we can never know when, where, by whom, or to what end any documentary artifacts created of us will be viewed.

As Erving Goffman elaborated more than 50 years ago, we all take on different roles in different social contexts. For Goffman, this represents not “a lack of integrity,” but the work each of us does, and is expected to do, in order to make social interaction function. In fact, it is those individuals who refuse to play appropriate roles, or whose behavior deviates from what others expect based on the situation at hand, who lose face and tarnish their credibility with others. The context collapse designed into most social media therefore complicates profoundly even the purposeful, asynchronous self-presentation that takes place on such websites, which has come to require “laborious practices of protection, maintenance, and care.”

When we internalize the abstracted and compounded documentary gaze, we are left with a Sisyphean disciplinary task: we become obligated to consider not just the situation at hand, and not just the audiences we choose for the documentary artifacts we create, but also every future audience for every documentary artifact created by anyone else. It is no longer enough to play the appropriate social role in the present moment; it is no longer enough to craft and curate images of selves we dream of becoming, selves who will have lived idealized versions of our near and distant pasts. Applying technologies of self starts to bring less pleasure and more resignation, as documentary consciousness stirs a subtle but persistent disquietude; documentary consciousness haunts us with the knowledge that we cannot be all things, at all times, to all of the others that we (or our artifacts) will ever encounter. Documentary consciousness entails the ever-present sense of a looming future failure.

As I discussed in Part II, the impacts of these inevitable failures are not evenly distributed. Those who have the most to lose are not people who are “evil” or who are “doing something they shouldn’t be doing,” but people who live ordinary lives within marginalized groups. Those who have the most to gain, on the other hand, are people who are already among the most privileged, and corporations that already wield a great deal of power. The greatest burdens of documentary consciousness itself are therefore likely to be carried by people who are already carrying other burdens of social inequality.

Recent attention to a website called WeKnowWhatYoureDoing.com showcased much of this yet again. The speaker behind the “we” is a white, 18-year-old British man named Callum Haywood (who’s economically privileged enough to own an array of computer and networking hardware), who built a site that aggregates potentially incriminating Facebook status updates and showcases them with the names and photos of the people who posted them. Because all the data used is “publicly accessible via the Graph API,” Haywood states in a disclaimer on the site that he “cannot be held responsible for any persons [sic] actions” as a result of using what he terms “this experiment”; he has further stated that his site (which is subtitled, “…and we think you should stop”) is intended to be “a learning tool” for those users who have failed to “properly [understand] their privacy options” on Facebook.

Coverage of the site’s rapid rise to popularity (or at least high visibility) was similar to coverage surrounding Girls Around Me: a lot of Shame On You, and the occasional critique that stopped at “creepy.” Tech–savvy white men thought the site was great; a young white woman starting college at Yale this fall explained that her digital cohort—“the youngest millennials, the real Facebook Generation”—has learned from the mistakes of “those who are ten years older than us.” As a result, her generation thinks Facebook’s privacy settings are easy, obvious, and normal; if your mileage has varied, “you have no one to blame but yourself.” In examining the screenshots from WeKnowWhatYoureDoing.com that these articles feature, I have yet to find one featured Facebook user who writes like a Yale-bound preparatory school graduate; unlike the articles’ authors, the majority of featured Facebook users in these screenshots are people of color. It is hard to see WeKnowWhatYoureDoing.com as doing anything other than offering self-satisfied amusement to privileged people, at the acknowledged potential expense of less privileged people’s employment.

Even overlooking the facts that Facebook’s privacy policy may be “more confusing and harder to understand than the small print coming from credit card companies,” and that the data in Facebook’s Graph API is really only “publicly accessible” in reference to a ‘public’ comprised entirely of software developers, the story Haywood wants to tell with WeKnowWhatYoureDoing.com is fundamentally flawed. It is a story in which “people violate their own privacies on a regular basis,” in a world where digital surveillance, companies like Facebook, and smug self-important software developers fade into the background of the setting’s ‘natural’ world. Haywood states, “[p]eople have lost their jobs in the past due to some of the posts they put on Facebook, so maybe this demonstrates why”; what he seems to be missing is that his site demonstrates not only “why,” but how people come to lose their jobs.

Even overlooking the facts that Facebook’s privacy policy may be “more confusing and harder to understand than the small print coming from credit card companies,” and that the data in Facebook’s Graph API is really only “publicly accessible” in reference to a ‘public’ comprised entirely of software developers, the story Haywood wants to tell with WeKnowWhatYoureDoing.com is fundamentally flawed. It is a story in which “people violate their own privacies on a regular basis,” in a world where digital surveillance, companies like Facebook, and smug self-important software developers fade into the background of the setting’s ‘natural’ world. Haywood states, “[p]eople have lost their jobs in the past due to some of the posts they put on Facebook, so maybe this demonstrates why”; what he seems to be missing is that his site demonstrates not only “why,” but how people come to lose their jobs.

In pretending that “information wants to be free” and holding individuals responsible for violations of their own privacy, we neglect to consider the responsibility of other individuals who write code for companies like Facebook, or who use the data available through the Graph API, or who circulate Facebook data more widely, or who help Facebook generate and collect data (yes, even by tagging their friends in photographs). If we cannot control our own privacy, it is because we can so easily impact the privacy of everyone we know—and even of people we don’t know.

We urgently need to rethink ‘privacy’ in ways that expand beyond the level of individual conditions, obligations, or responsibilities, yet also take into account differing intersections of visibility, context, and identity in an unequal but intricately connected society. And we need as well to turn much of our thinking about privacy and individual autonomy on its head. Due justice to questions of who is visible, and to whom, to what end, and to what effect cannot be done so long as we continue to believe that privacy and visibility are simply neutral consequences of individual choices, or that such choices are individual moral responsibilities.

We must reconceptualize privacy as a collective condition, one that entails more than simply ‘lack of visibility’; privacy must be also a collective responsibility, one that individuals and institutions alike honor in ways that go beyond ‘opting out’ of the near-ubiquitous state and corporate surveillance we seem to take for granted. It is time to stop critiquing the visible minutiae of individual lives and choices, and to start asking critical questions about who is looking, and why, and what happens next.

Whitney Erin Boesel (@phenatypical) is a graduate student in Sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Looming storm photo by Whitney Erin Boesel. Used with permission.

Digital eye image from http://www.indypendent.org/2012/04/28/facebook-lobbies-washington-spying-users

Store surveillance image from http://mastersofmedia.hum.uva.nl/2010/10/30/facebook-open-minded-panopticon/

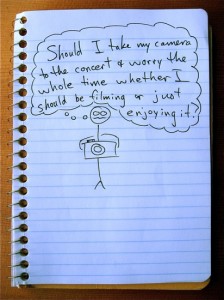

Stick figure comic by Luke Simpson, from http://www.stickworldcomics.com/comics/2009/11/

Camera shy photo by M1L4N, from http://m1l4n.com/camerashy/

Impossible task image by Hyeyoung Kim, from http://www.co-mag.net/2008/dark-word-hyeyoung-kim/

Facebook traffic sign photo from http://epicfails.net/2011/10/facebook-fail/

Facebook gunshot image from http://www.buzzingup.com/2010/09/facebook-is-infected-by-the-failwhale/

New look image by Kyle Froman from http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/2011/10/starting_over.html

Comments 8

nathanjurgenson — July 19, 2012

love the essay!

taking on your call to both take into account more of the complexities involved in social media documentation as well as imagining 'what is next', i wonder if we are assuming in our analyses today's norms and stigma's about privacy when looking at these new trends. these norms and stigmas certainly won't be the same in the future, in some way or another. to get to my point, and in reference to your quote above: it might be increasingly impossible for individuals to really take on all of this complex matrix of intersecting concerns. i'd like to argue that while you make the case why it would be beneficial to do this, i am not convinced it is possible.

it might be the case that that some of the stigma attached to not thinking of every possible documentation scenario--and they are proliferating by the moment--will fade because errors will be increasingly commonplace. i'll concede that stigma will fade for some quicker than others. we'll forgive privileged folks while asking the impossible of the rest. in fact, i wrote about that once: http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2010/11/19/facebook-skeletons-can-be-forgiven-unless-you-are-female/

in any case, i think the possibility that norms will change in the future should be addressed.

really dig this essay series, and hope for more soon!

whitneyerinboesel — July 20, 2012

thank you for this!

to clarify, i'm not advocating that individuals necessarily should (or even can) take on such an impossibly "complex matrix of intersecting concerns" (nicely put, thank you). i'm saying that, in the present moment, the task of considering that matrix (and then acting accordingly) is implicitly demanded of us--and that it is precisely the impossibility of such a task, combined with the potential consequences of failing at it (eg, a lost election, as you point out), that leads to a particular kind of anxiety.

you're right to say that the (range of) norms may well change in the future, and i think norms could change *for the better* in the future if that's the future we work to create (after all, it's not determined). but positive change won't happen in the way that silicon valley likes to pretend it will, with everyone sharing everything until suddenly *poof!* no more stigma! *-isms be gone! rather, the price of establishing new norms will be paid most heavily by those who already bear the brunt of existing norms' negative impact.

in the meantime, because we simply cannot know if or in what ways social norms will change (for whom) (in which contexts), any calculation about the future risk of a recent-past artifact is inherently a gamble--and as can be extrapolated from the article you linked, both the stakes and the risks of such bets vary widely across different social groups. this is in large part why i want to call 'shenanigans' both on the expectation that we manage and calculate those risks, and on the demand that we throw caution to the wind in some kind of misguided "bare all for utopia!" pseudo-movement. the calculations simply can't be done, and the prices of failure will *not* be egalitarian.

in my recent observations (admitted: non-representative peer group convenience sample), more people make decisions about what to share online based neither on rational matrix calculations nor on activist visions of creating a better world; rather, they bend (or outright break) 'social rules' in their online self-presentations out of resignation. since it hardly seems worth it to fight the losing battle of self-policing, they half-push the envelope...and then hope for the best, while bracing for the worst.

In Their Words » Cyborgology — July 22, 2012

[...] “we are attuned not only to possibilities of documenting, but also to possibilities of being document...” [...]

JennyDavis — July 22, 2012

Great post Whitney,

I find that our work and thoughts heavily intertwine. I'm working on (trying to FINALLY send out) a piece on self-triangulation (much of what you talk about here). There's a great article by Walther et al. that I use a lot in the paper. They talk about the relative weight of other-generated (versus self-generated) information. I think it speaks a lot to what you do here. Here's a link if you want to check it out.

http://crx.sagepub.com.lib-ezproxy.tamu.edu:2048/content/36/2/229

Possibility vs. Potentiality: A Case Study in Documentary Consciousness » Cyborgology — July 26, 2012

[...] the last part of my recent essay “A New Privacy,” I described documentary consciousness as the perpetual (and [...]

A New Privacy: Full Essay (Parts I, II, and III) » Cyborgology — August 6, 2012

[...] Agency and the Myth of Autonomy Part II: Disclosure (Damned If You Do, Damned If You Don’t) Part III: Documentary Consciousness Privacy is not dead, but it does need to [...]

Documentary Oversaturation » Cyborgology — January 28, 2013

[...] Erin Boesel used this similar term in her post, however, I am using it differently than she defines it there. Lead image from the Cats and Cameras [...]