Below is a three part essay I presented at the 2012 Southwest Texas Popular Culture Association meetings in Albuquerque, New Mexico on February 9th. It was presented as part of a series of panels titled “The Apocalypse in Popular Culture.” A (much) earlier version of this paper can be found on the Sociological Images sister blog.

THE ZOMBIE IN FILM: FROM HAITIAN FOLKLORE TO APOCALYPTIC ANXIETIES

Part 1: The Early Cinematic Zombie

Bishop’s (2010:20) “taxonomy” of the dead” is a useful for articulating the different conceptualizations of the zombie as it has appeared in film. In my opinion, however, the zombie can be reduced to three main types: the somnambulist (ie: mind control slave-zombie), the cannibalistic corpse (ie: undead eaters), and the infected living (eg: the “rage virus” of 28 Days Later).

Bishop’s (2010:20) “taxonomy” of the dead” is a useful for articulating the different conceptualizations of the zombie as it has appeared in film. In my opinion, however, the zombie can be reduced to three main types: the somnambulist (ie: mind control slave-zombie), the cannibalistic corpse (ie: undead eaters), and the infected living (eg: the “rage virus” of 28 Days Later).

With the development of the motion picture, the zombie became a staple of horror, and a popular movie monster. The first major zombie film was Halperin and Halperin’s (1932) White Zombie, which depicted a Haitian voodoo priest capturing the female protagonist as a zombie slave. Other early zombie films include: Revolt of the Zombies (1936), King of the Zombies (1941), and I Walked with a Zombie (1943). What is important to note is that the zombie of these films was not the cannibalistic creature we now know it as. These zombies were people put under a spell, the spell of voodoo and mystical tradition. In these films, the true terror is not be being killed by zombies, but of becoming a zombie oneself.

In the 1950s, zombie films came to the American shores. At this time of Cold War anxiety, films oriented around mind control and invasion from afar resonated with audiences. Films like Invisible Invaders (1952) presented the dangers lurking nextdoor, as family, friends, and neighbors turned on one another. In this film, a mad scientist uses technology to secure power over men’s brains. In films such as these, fears of loss of individuality and loss of control over the self become predominant. This mirrors the changes of suburban America at this time, as expansion into the suburbs and the development of mass-production led to new forms of consumption and identity creation. Films like The Last Man on Earth (1964) portray the fight for individuality as Vincent Price, as the last man on earth, must fight off the onslaught of night-walking, vampire/zombie hybrids.

Also, after the devastation of the atomic age was realized in Hiroshima ad Nagasaki, new anxieties developed surrounding science and technology, the limitations of human progress, and the dangers posed by new forms of energy we did not yet fully understand. Films like Plan 9 From Outer Space (1959) root the zombie in terms of these fears, portraying the inevitable apocalypse as arising out of humanity’s own hubris. Developments in science and technology, especially the desire to control nature through new forms of energy, lead extraterrestrials to intervene to stop humanity’s inevitable acquisition of these dangerous weapons of mass destruction. The aliens resurrect the dead in order to destroy the living. In these dramatic premonitions of the future, humanity is said to be facing retribution for its sins. In the 1970s, these fears would only be magnified…

Part 2: Romero and the Politicized Zombie

Romero’s 1968 classic, Night of the Living Dead, revolutionized the zombie metaphor. His “flesh eaters” have since become a staple of the genre and the social criticism laced within his early films have become a tradition in subsequent zombie films. Prior to Romero’s take on the zombie genre, zombies largely reflected the spirit of the times in which these films were made. Hence, the fears of racial miscegenation found in White Zombie (1932) and the fears of mind control found in Invisible Invaders (1952). However, Romero changed these trends when he made the zombie into something more than simply an automaton of mind control or voodoo mysticism; Romero introduced the “flesh-eater” into the zombie lexicon, pushing the genre further into the macabre and raising the possibility of a politicized zombie figure.

In fact Night of the Living Dead was created as a critique of the violence and devastation of Vietnam, with the dead returning to life as a result of radiation emitted from a government “Venus probe” sent to space. In addition, Romero made his zombies into a form of contagion: A single bite from a zombie will similarly kill and turn one into a zombie, thereby playing into fears of loved ones and strangers turning on one another. Since Romero’s film, the zombie has usually been associated with cannibal corpses that have risen from the grave to devour the living.

What is interesting to note about Romero’s film is its not-so-subtle use of race relations to depict the tensions of the Civil Rights era. Although Romero himself has stated that his casting of a Black man as the lead role had nothing to do with race, the impact was felt by audiences, who saw the film as ahead of its time. To make this allegory all the more palpable, Romero included still photography at the end of the film, in which militant white police officers drag the corpse of Duane, the lead character, by meathooks, accompanied by canines and armed civilians. These photos, shocking in their graphic violence, are reminiscent of white lynchmobs in the southern United States.

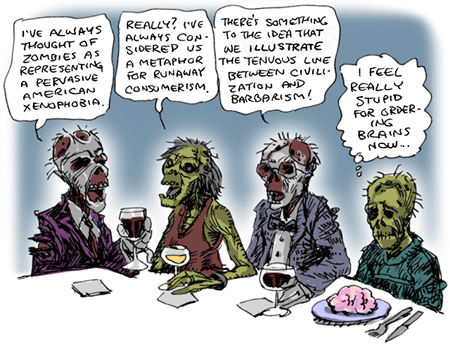

Romero took his social criticism one step further in his second zombie film, Dawn of the Dead (1978). In this film, protagonists bunker down in a shopping mall as zombies invade from outside. The images of zombies mindlessly walking, groping, and drooling over consumer goods provides a stark image of the cult of consumerism and American capitalism.

Finally, The Plague of the Zombies (1966) captures themes of colonialism, tyranny, and proletariat exploitation. Set in the mid 1800s, a mysterious plague caused by voodoo magic leads the rural proletariat into a zombie revolution, eventually overtaking their corrupt patriarch and devouring him.

In short, the films of the 1970s became extremely political, as the zombie became a metaphor for various social anxieties that were most salient at this time, including environmental degradation, science and technology, rising inequality, energy crises, and consumer culture.

With the 1980s, the zombie turned into a comedic figure. The films became more formulaic and less dramatic, mainly as a result of low-budget production houses capitalizing on the success of early zombie films. These exploitation films revolved around ever-increasing levels of gore and nudity in order to attract young audiences with shock value. Films like Return of the Living Dead (1985), Dead Alive (1992), and Redneck Zombies (1989) capture this era of Grindhouse cinema.

Nonetheless, the zombie films of this era still contain social commentary. For instance, themes of drug abuse and teen promiscuity feature prominently in these films, mirroring the social context of the 1980s, particularly Reagan’s “War on Drugs” and the AIDS epidemic. Similarly, Romero’s third zombie installment, Day of the Dead (1985), is credited as a criticism of Cold War international relations and the U.S. military-industrial complex.

As we can see from the examples above, Romero successfully turned the zombie from brainless automaton into a premier source of social and cultural criticism. The cannibalistic nature of his “flesh eaters” and the precedents he set for the genre helped to transform the zombie into powerful figure for social commentary. Next week, I will cover Part 3: The Zombie Renaissance and conclude with some theory signifying the importance of the zombie as metaphor.

Scholars have called the post-9/11 era the “Zombie Renaissance” due to the torrent of zombie films produced at this time and the paradigmatic changes introduced to the zombie as movie monster (Bishop 2010). The first blockbuster film of this era, Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later (2002) is often credited to raising the stakes in zombie films. This film became a powerful drama oriented around the zombie apocalypse, something that has since been mimicked in recent films and especially in AMC’s recent television series The Walking Dead.

Perhaps most importantly, Boyle’s film is also credited in the creation of a new breed of zombie, the fast-moving, disease-infected living type I outlined at the onset of this presentation. These zombies are no longer depressed automatons, but enraged, feral, and overcome with madness. They sprint rather than shuffle; and more than brains they seek to spread the infection further, spewing blood and bile onto their victims in addition to devouring them.

28 Days Later also set the stage for a dramatic expansion of the zombie narrative, both in terms of special effects and in scope. In the film, the entire world is said to have succumbed to the “rage virus” and the protagonists must struggle to survive without the safety of social institutions. In fact, the very social institutions established to protect humanity become threats to survival, as the protagonists find out when they bunker down with renegade soldiers who attempt to rape and kill them.

The themes of social decay portrayed so eloquently in 28 Days Later have since become a staple of the zombie genre. This is made most salient in films that draw direct parallels to global terrorism and social unrest. Zombie films like Dawn of the Dead (the 2004 remake of the Romero classic) take this to a new level, portraying dystopian anarchy on a grand scale that could not be achieved in early renditions of the zombie apocalypse. With characters left to fend for themselves, these “everyman” tales become gripping stories of individualism and resilience, thereby resonating with Western audiences.

But the social criticism of earlier zombie films was not lost in these recent films. Romero, particularly, has been keen to maintain explicit social commentary in his recent films. His more recent, Land of the Dead (2005) has often been credited as an indictment of the Bush era corporate-political inbreeding, in which the rich close themselves off in the opulent Fiddler’s Green while the masses wallow in filth on the streets below, forever at risk of zombie invasion. In addition, the very structures enacted to protect us actually become our own undoing, as the barricades constructed to keep out the zombie horde ultimately serve to prevent the characters’ escape.

Finally, the zombie has acquired a powerful cultural currency since 9/11. It has spawned powerful new narratives of society and the individual, and invigorated gun enthusiasts and doomsdayers with models for survival (Dendle 2008). It has led to a distinct subculture of horror fans that identify with the zombie, inspiring “zombie walks” across the country and spurring fan communities across the globe. Given that the collective consciousness continues to identify so strongly with the zombie narrative, we will probably only see more zombie related media and activities emerging in the near future. In fact, we already have college courses and anthologies dedicated to the zombie. In this sense, the zombie will live on as part of our cultural understanding of mass society, offering us an image of the future but also a critique of the present state of the social order.

Comments 6

Bibliography | The Sis — March 24, 2012

[...] Stronhecker, David Paul. “The Zombie in Film.” The Society Pages, February 27, 2012. http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2012/02/27/the-zombie-in-film-full-essay-parts-i-ii-and-iii/. [...]

The Crown of Being (a review) – Part I: The Embodied Virtual » Cyborgology — April 27, 2012

[...] present has come to look the way it does, and as a means for the imagining of potential futures (also zombies). Indeed, the term cyborg always brings with it a host of connotations firmly rooted within SF, [...]

Deacon Frost — October 31, 2012

Interesting article. What I think is missing in this analysis is the aspect of

using the non-human nature of the zombie as a means of "getting away" with depicting gore and utmost graphical violence in almost pornographic form

in recent productions, especially "The Walking Dead", "Resident Evil" etc.. IMHO this takes the genre far away from any "social commentary" towards an instrument for desensitizing audiences and alluding to most primal fears (or worse) urges...

John Farnum — November 28, 2012

I really agree with Deacon Frost's addition to this critique.

Dave — January 16, 2013

Deacon has a valid point in that analysing the growing violence in these films is a worthwhile venture, though I disagree that studios feel they need a reason to "get away" with such violence - Saw, Wolf Creek, Etc all have a lot more violence and do not need the "zombie" clause. The violence in these films certainly doesn't take away the social commentary, though it may mask it. Deacon appears (though I could be mistaken) to suggest that the violence is a deliberate tool with the purpose of desensitization, to which I would suggest that he is mistaken. The only outcome studios are interested is money. And in fact, they are (more often than not these days) sanitizing content down in violence and sexuality, so that they can market products to the biggest consumer audience - kids.

Hunger Games is a classic example. (SPOILER ALERT) The wolves at the end of the film were, according to the books, rebuilt from the broken bodies of the fallen tributes, (essentially - zombie wolves!). Our hero (can't recall her name - Cat?) has to face the zombie wolf of a friend she failed to save - an emotional ordeal for anyone to overcome and a true test of character. The film opted for clearly cgi wolves which were just software created by the gamesfolk. With nothing human or even real about the wolves, the emotion that comes from being forced to kill one is irrelevant.

TLDR: Social Commentary of zombies is relevant no matter how violent, and studios will do anything for a buck!

Jason — June 22, 2013

Great essay and very well thought out. The only thing I noticed was that you mentioned that Invisible Invaders was a "mad scientist" and "mind control". It was actually about aliens possessing the bodies of the dead for world domination. The scientists were trying to capture and stop them.

"Films like Invisible Invaders (1952) presented the dangers lurking nextdoor, as family, friends, and neighbors turned on one another. In this film, a mad scientist uses technology to secure power over men’s brains."

"Sequestered in an impregnable laboratory trying to find the aliens' weakness, Penner, his daughter, a no-nonsense army major and a squeamish scientist are attacked from outside by the aliens, who have occupied the bodies of the recently deceased."