[SPOILER ALERT: details about the first episode of Sherlock“A Study In Pink” are discussed below. The ending is not totally given away, but major story details are revealed.]

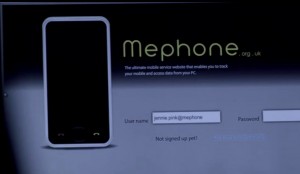

A few weeks ago, I challenged Kurt Anderson’s claim that cultural progress and innovation had stagnated in the last twenty years. Anderson, I contend, has ignored new mediums (the Internet), re-invented genres (hip-hop, electronic music), and new cultural stereotypes (geek chic, hipsters). But what ties all of these things together is the central thesis that consumer technologies are just as much cultural artifact as clothes or music. No where is this more obvious and brilliantly executed than in BBC One’s updated interpretation of the Sherlock Holmes mysteries. Set in present day London, “Sherlock” is a reinterpretation of the most famous Holmes mysteries and does an excellent job of translating the Victorian source material into a modern drama. That translation includes dress, idiomatic expressions, and vehicles- but it also includes cell phones, restrictions on smoking, and the War on Terror. Sherlock is a uniquely 21st century show that could not have taken place in the early 2000s or the 90s.The first episode, “A Study in Pink” is a loose adaptation of the first Sherlock Holmes mystery penned by Arthur Conan Doyle titled, “A Study in Scarlet.” (I’ll refer to them from now on as “pink” and “scarlet” respectively.) In both scarlet and pink, Holmes and Watson meet for the first time in a chemistry lab. They agree to be roommates, and immediately fall into a case involving the mysterious poisoning death of a woman [In “scarlet” its actually a man, see the first comment below] who has written “RACHE” (german for revenge) just before her death. In “pink” the word is revealed to be the password on a tracking service on a conspicuously missing mobile phone. The tracking service helps find the killer. In “scarlet” the word refers to revenge for a lost lover, and her missing ring brings the killer to Holmes. Two very similar plot lines, dramatically altered by the realities of technology. While “scarlet” requires putting an ad in a local paper (a paper that has a circulation of only a portion of London- a victorian technology), “pink” uses cell phone tracking and texting. What would this story look like in the 90s? It is difficult to say and I think that is very telling. As The Telegraph’s Olly Grant put it:

There are some good arguments why modernising Holmes might be an unexpectedly good idea. First, Conan Doyle’s tales did once feel genuinely modern; snappy, action-oriented, always more concerned with plot than period details. Second, many of the Holmesian “trimmings” were invented by others; the curly pipe, for example, was introduced by playwright and actor William Gillette in the 1890s.

The Holmes and Watson adventures then, are a good framework for showcasing your era’s overlooked and seldom noted material culture. For example, in both the original stories and Sherlock, Holmes deduces that Watson has a drunk for a brother, whom he rarely speaks to, and who has recently left his wife. He knows this because Holme’s watch has the tell-tale scratches around the key hole of an alcoholic’s shaking hands. Every night, when he goes to wind the watch, he misses a few times and scratches the case. In the 21st century version, the scratches are found around the charger of a smartphone.

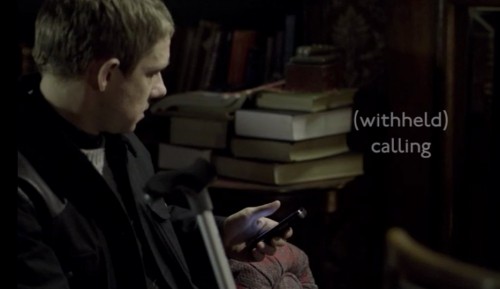

The actual existence of a mobile phone in a movie or television show, does not necessarily distinguish it from the last twenty years of media. What does distinguish it from, say 2002- is the ubiquity (and hence, mundanity) of the mobile phone and the central role it plays within the storyline. It is a link to the killer, but we are not supposed to be surprised or impressed that a mobile phone is being used. Its just a good clue:

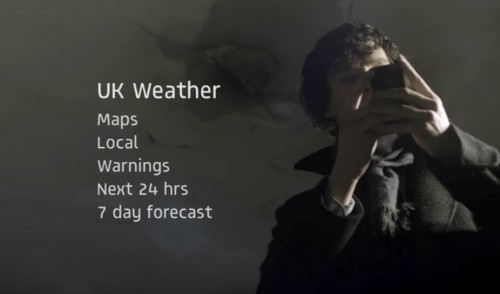

I was most impressed by how cell phone usage was prominent, but did not become a magical technology. The technology gives us useful information, but it cannot solve the crime. We see Holmes check the weather:

Comments 13

Brigid Keely — January 25, 2012

/pedantic nitpick: in "scarlet" two dudes are murdered and it's because of the death years ago of the same woman. Holmes isn't investigating the death of a woman at all.

I like how technology is incorporated into "Sherlock." When I started watching "Bones," I was excited because it covered a field I'm interested in. But then they busted out magical problem solving technology. Look. The actual way problems are solved is really cool, if not good tv. You don't REALLY need magical computer imaging flashy fake stuff to tell a compelling story.

Katrin Bongard — January 27, 2012

and it´s the same with "The Artist"

Sherlock: A Perspective on Technology and Story Telling ... | Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective | Scoop.it — January 29, 2012

[...] background-position: 50% 0px; background-color:#222222; background-repeat : no-repeat; } thesocietypages.org - Today, 5:48 [...]

Sherlock: A Perspective on Technology and Story Telling » Cyborgology | New storytelling formats | Scoop.it — February 13, 2012

[...] background-position: 50% 0px; background-color:#222222; background-repeat : no-repeat; } thesocietypages.org - Today, 11:29 [...]

Sherlock: A Perspective on Technology and Story Telling » Cyborgology | Film Futures | Scoop.it — February 13, 2012

[...] background-position: 50% 0px; background-color:#222222; background-repeat : no-repeat; } thesocietypages.org - Today, 2:28 [...]

Sherlock: A Perspective on Technology and Story Telling » Cyborgology | film and film in digital age | Scoop.it — February 14, 2012

[...] background-position: 50% 0px; background-color:#222222; background-repeat : no-repeat; } thesocietypages.org - Today, 9:01 [...]

Sherlock: A Perspective on Technology and Story Telling | Transmedia: Storytelling for the Digital Age | Scoop.it — February 20, 2012

[...] } #themeHeader #titleAndDescription * { color: black; } thesocietypages.org - Today, 1:50 [...]

Sherlock: A Perspective on Technology and Story Telling | Tech happens! | Scoop.it — February 21, 2012

[...] background-position: 50% 0px; background-color:#222222; background-repeat : no-repeat; } thesocietypages.org - Today, 6:54 [...]

Sherlock: A Perspective on Technology and Story Telling | Teaching&Learning | Scoop.it — February 21, 2012

[...] background-position: 50% 0px; background-color:#222222; background-repeat : no-repeat; } thesocietypages.org - Today, 7:51 [...]

Sherlock: A Perspective on Technology and Story Telling | Transmedia + Storyuniverse | Scoop.it — February 22, 2012

[...] background-position: 50% 0px; background-color:#222222; background-repeat : no-repeat; } thesocietypages.org - Today, 2:59 [...]

La Regenta tróspida « 140 y más — March 31, 2012

[...] “La tecnología nos da información útil, pero no resuelve el crimen”. Ese es el quid. Aunque eso no quita que María Teresa Campos diga en su programa que ha olvidado su contraseña de Facebook o que en Twitter se comente con avidez el modelo de sus zapatos. Es la grandeza del medio. Y si no, que se lo pregunten a los tróspidos y compañía. [...]

Anthony — May 4, 2012

A friend recommended Sherlock, so I saw the first episode and was absolutely floored by how well done it was and rate it a 10, just magnificent, flawless production and performance. Then I saw the second episode and was extremely disappoined; they should have called it "Sherlock meets the Pink Panther", because it was trying to mix what was a serious detective/mystery story with the implausable and comedic devices from "The Pink Panther". I *really* hope this isn't the direction the rest of the series is headed. I'll watch one or two more but if it doesn't continue the same standard set in the first episode then I won't continue wasting my time.

Enhance! Ugly Websites, Flip Phones, and the Trouble With Technology in Storytelling. » Cyborgology — January 9, 2014

[…] groundbreaking shows like Sherlock have found ways to portray conversation without an over-the-shoulder shot of a computer screen, and […]