The New York Times recently highlighted recent research by sociologists Neil Gross and Ethan Fosse on the tendency for professors to be liberal:

New research suggests that critics may have been asking the wrong question. Instead of looking at why most professors are liberal, they should ask why so many liberals — and so few conservatives — want to be professors.

In their findings, Gross and Fosse chalk this one up to typecasting:

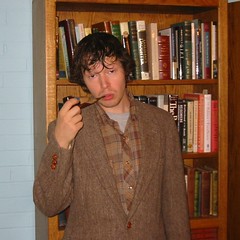

Conjure up the classic image of a humanities or social sciences professor, the fields where the imbalance is greatest: tweed jacket, pipe, nerdy, longwinded, secular — and liberal. Even though that may be an outdated stereotype, it influences younger people’s ideas about what they want to be when they grow up.

Jobs can be typecast in different ways, said Neil Gross and Ethan Fosse, who undertook the study. For instance, less than 6 percent of nurses today are men. Discrimination against male candidates may be a factor, but the primary reason for the disparity is that most people consider nursing to be a woman’s career, Mr. Gross said. That means not many men aspire to become nurses in the first place — a point made in the recent Lee Daniels film “Precious: Based on the Novel ‘Push’ by Sapphire.” When John (Lenny Kravitz) asks the 16-year-old Precious (Gabourey Sidibe) and her friends whether they’ve ever seen a male nurse before, all answer no amid giddy laughter.

Nursing is what sociologists call “gender typed.” Mr. Gross said that “professors and a number of other fields are politically typed.” Journalism, art, fashion, social work and therapy are dominated by liberals; while law enforcement, farming, dentistry, medicine and the military attract more conservatives. “These types of occupational reputations affect people’s career aspirations,” [Gross] added.

Gross adds a bit of history to where this typecasting came from:

From the early 1950s William F. Buckley Jr. and other founders of the modern conservative movement railed against academia’s liberal bias. Buckley even published a regular column, “From the Academy,” in the magazine he founded, The National Review.

“Conservatives weren’t just expressing outrage,” Mr. Gross said, “they were also trying to build a conservative identity.” They defined themselves in opposition to the New Deal liberals who occupied the establishment’s precincts. Hence Buckley’s quip in the early 1960s: “I’d rather entrust the government of the United States to the first 400 people listed in the Boston telephone directory than to the faculty of Harvard University.”

In the 1960s college campuses, swelled by the large baby-boom generation, became a staging ground for radical leftist social and political movements, further moving the academy away from conservatism.

Gross and Fosse also note that stereotyping is not the only reason for the liberal leanings of the academy:

The characteristics that define one’s political orientation are also at the fore of certain jobs, the sociologists reported. Nearly half of the political lopsidedness in academia can be traced to four characteristics that liberals in general, and professors in particular, share: advanced degrees; a nonconservative religious theology (which includes liberal Protestants and Jews, and the nonreligious); an expressed tolerance for controversial ideas; and a disparity between education and income.