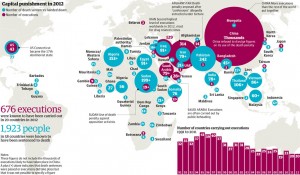

Despite recent declines, the United States still has one of the largest prison populations among comparable nations. Most of those incarcerated in U.S. prisons will eventually be released. Evidence suggests that as many as 600,000 individuals are released from prison each year. Upon release, many people must serve time on parole, which typically involves a period of supervision with a set of conditions that a parolee must follow, such as passing a drug test. In a recent article in The Conversation, Shawn Bushway and David Harding discuss how violations of parole conditions appear to be a key driver of high prison populations, rather than new offenses.

Since people convicted of a felony are randomly assigned judges in Michigan, Bushway and Harding, along with their colleagues Jeffrey D. Morenoff and Anh P. Nguyen, conducted a “natural experiment” to account for how an individual’s background may influence their sentences. As the authors explain,

“This random assignment of judges mimics the way a scientist would design a randomized, controlled experiment in the lab. There are no obvious differences between who gets randomly assigned to one judge and who gets assigned to the other. For all intents and purposes, the groups are identical. So if one group ends up with stricter sentences, it’s likely due to the judge’s predilections rather than to anything specific to the individual defendants and their crimes.”

The authors are thus able to understand the specific effects of parole violations. Their findings suggest that people who are imprisoned and then released to parole — rather than those who are put on probation (instead of incarceration) initially — are more likely to return to prison. Further, some scholars remain skeptical that probation may also be another avenue into the prison system. Overall, the work of social scientists suggest that if we want to reduce prison populations, we must reevaluate parole and probation practices, including the response to violations of supervision conditions.