Following taunts from President Trump and other Republican officials, Democratic Senator Elizabeth Warren took a DNA test to “prove” her American Indian ancestry last fall. However, the political spectacle did not involve the Cherokee Nation’s determinations of who can rightfully claim their heritage, and for many American Indians, DNA tests have no bearing on deciding tribal heritage. The weight placed on these tests today harkens back to antiquated concepts of race, ethnicity, or tribal status as genetics — stripping the historical, cultural, and social meanings that shape them. Outsider attacks on tribal sovereignty are also an example where American Indian identity has been defined and controlled in the United States. In a recent Weekend Edition on NPR, social scientists weigh in on how determinations of American Indian identity have changed over time, and how who is “counted” as American Indian often depends on the method used for evaluating this identity.

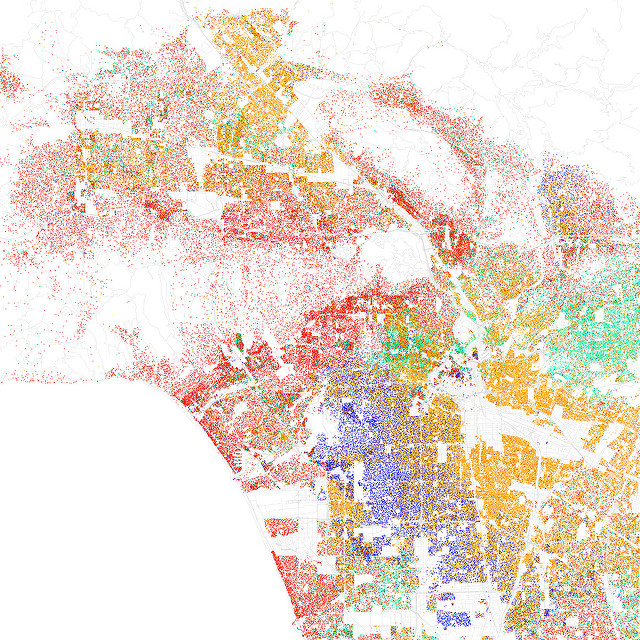

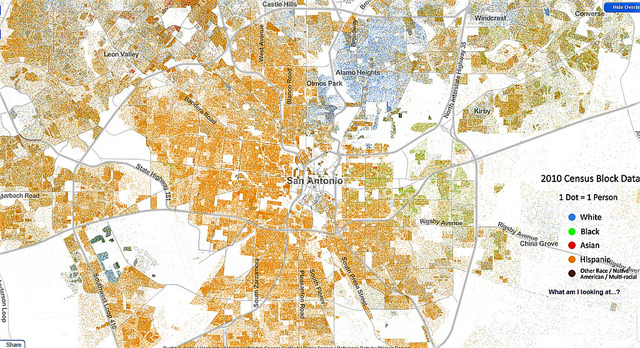

Throughout the latter half of the twentieth century, the U.S. Census has been key in tracking shifts for—and perhaps even influencing—the likelihood for one to identify as American Indian. According to census statistics, the American Indian population tripled from 1960 to 1990. Sociologist Carolyn Liebler argues that this shift is due to changes in the way the Census measured racial identity; instead of relying a census worker’s determination of someone’s race, participants were allowed to choose their own race starting in 1960. According to Liebler, before 1960 census workers

“[were] not necessarily going to see a person who’s American Indian as American Indian. And it was fairly rude, as kind of it is now, to ask someone what race they are. So the [census worker] would just write it down.”

The ability for one to self-classify, therefore, is likely part of the change in population. Anthropologist Russell Thornton, a member of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, believes that the change may also be due to American Indian activism. He argues that the Civil Rights Movement empowered American Indians to be activists and lay claim to American Indian identity. According to Thornton,

“People that didn’t want to admit any Indian ancestry now thought it was kind of OK to be, quote, ‘Indian’ – even fashionable.”

Even the process to legitimate one’s claim as American Indian—and a citizen of a particular tribe—is debated in some tribal nations. Sociologist and member of the Cheyenne Nation, Desi Rodriguez-Lonebear states,

“[This process] has broken up families. It influences who individuals choose to partner with and have children with. It really permeates every part of our existence, in reality, as native peoples.”

Serving as an advisor for the Census Bureau, she urges policy makers and researchers to listen to American Indian communities as identities continue to shift and change.