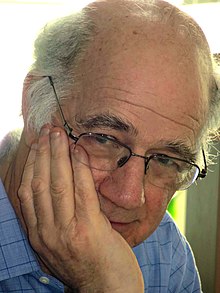

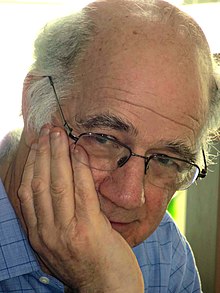

Robert Putnam (Professor Emeritus of Public Policy at Harvard University) was interviewed in a segment for PBS News Hour on discussing the effects of social isolation on civic engagement: “That is a primary cause of the Trump phenomenon. … When people are socially isolated, as we are increasingly, they become vulnerable to populist appeals.” Putnum’s most recent book, The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do it Again, highlights the parallels between modern American and the late 1800s–a deeply fragmented, individualistic, and polarized time period. Putnam describes how an “explosion” of new civic, religious, and social groups sparked a “moral revival” that led people to think in more collective ways: “People began to say, wait a minute, it’s not all about us. We have obligations to other people.”

Florence Becot (Lead of the Agricultural Safety and Health Program at Penn State University) appeared on The FarmHouse–a podcast by Lancaster Farming–to discuss the unique stressors on women in agriculture. Becot described that many women take on “invisible work” on farms, including raising children while still performing farm work. “Raising children on the farm is wonderful. So many moms talked about how much they love having the children around. They wouldn’t do it any other way,” Becot said. “But the reality is, we’ve talked to women farmers who said if I was a nurse at the hospital, I wouldn’t be allowed to bring my kid. Why is there this weird expectation that I should have my kid with me when I’m driving this really heavy piece of machinery?”

Battle for Tibet, a new documentary from FRONTLINE, examines China’s rule over Tibet. The film features Tibetan sociologist Gyal Lo’s study of Chinese boarding schools for Tibetan children. The Chinese government claims that these schools promote “human rights and cultural heritage protection.” However, Lo found that there were two main focuses in the boarding schools: “One is to instill the communist ideology and the second is to instill Chinese culture. These two subject areas of teaching are being implemented to change the Tibetan children’s mindset.” Lo warns that “Over the next 15 to 20 years, if boarding schools continue, Tibetan national culture and identity will be completely destroyed.”

Willam Robinson (Professor of Sociology at the University of California-Santa Barbara) spoke at the Peoples’ Platform Europe 2025, discussing the “unprecedented crisis in global capitalism.” Robinson described four main elements of the crisis: 1) stagnant, concentrated economic systems, 2) billions of people treated as “disposable”, 3) the rise of authoritarianism, and 4) environmental destruction. Robinson said. “Never has the slogan ‘resist to exist’ been more opportune and appropriate.” This story was covered by Medya News.