Young people have always tended to get into some trouble here and there. What’s shocking, though, is how often young Americans are being arrested–in fact, by the age 23, nearly a third of Americans will have been arrested for a crime other than a moving violation. This stat is reported by the New York Times and comes out of a study by Shawn Bushway, a criminologist at the State University at Albany, and Robert Brame, a professor of criminal justice and criminology at the University of North Carolina-Charlotte. Their work analyzed data from the federal government’s National Longitudinal Survey of Youth.

Bushway and Brame found that the current arrest ratio (30.2 percent of young adults having been arrested for things other than a minor traffic violation) was a significant increase from 22 percent back in 1965. According to the researchers, this could be a result of an increasingly aggressive and punitive judicial system that has given rise to more drug related offenses and zero-tolerance policies in schools. According to Bushway:

This estimate provides a real sense that the proportion of people who have criminal history records is sizable and perhaps much larger than most people would expect.

Brame says that he hopes the study, which was appeared in the journal Pediatrics, could help alert physicians to signs that their young patients could be at risk. As he said in USA Today, “Arrest is a pretty common experience,” but still, “We know that arrest occurs in a context,” Brame told the Times. “There are other things going on in people’s lives at the time they get arrested, and those things aren’t necessarily good.” If doctors can intervene, he added, “It can have big implications for what happens to these kids after the arrest, whether they become embedded in the criminal justice system or whether they shrug it off and move on.”

Regardless of the study’s intended audience, the fact that nearly a third of young adults has an arrest record is a serious manner, especially in an era in which many employers routinely conduct criminal background checks and youth records that should be sealed are often found to be publicly available on the Internet.

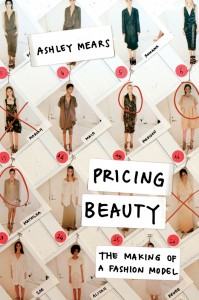

d spent some time in the New York fashion scene and looked closely among the high heels, you might have spotted one model taking scrupulous field notes as seriously as she took the runway. Ashley Mears, assistant professor of sociology at Boston University and author of the book Pricing Beauty, immersed herself into the world of modeling by actually becoming a model. A recent

d spent some time in the New York fashion scene and looked closely among the high heels, you might have spotted one model taking scrupulous field notes as seriously as she took the runway. Ashley Mears, assistant professor of sociology at Boston University and author of the book Pricing Beauty, immersed herself into the world of modeling by actually becoming a model. A recent