Just like April’s TSP Media Award for Measured Social Science winner Barbara Risman, there have been quite a few examples lately of sociologists contributing their thoughts and talents to opinion pieces for major news sources. Last week, the New York Times featured op-eds from Arlie Russell Hochschild and Elizabeth Armstrong.

First, Hochschild, a professor emerita of sociology at the University of California, Berkeley, wrote about the expanding presence of the capitalistic marketplace in our personal lives. It may seem like second nature to hire a professional to help with a task or develop a skill we lack. But, according to Hochschild’s piece, the sheer extent of services available for purchase is shocking: dating coaches, rental friends, and professional potty trainers. Hochschild goes on to look at some of the more invasive manners in which the market has seeped into our intimate lives, as well as what this says about our society.

Hochschild brings in the work of Michael Sandel, a professor of government at Harvard, who adds that you can now purchase an upgrade in prison cells in California or buy carpool lane access for solo drivers in Minneapolis (see more, here, with Sandel in recent interview on The Colbert Report about the moral limits of the marketplace).

This increasing tendency to hire professionals to take on personal tasks, Hochschild writes, has some unexpected consequences. She describes our ever-increasing relationship with the free market as a self-perpetuating cycle:

The more anxious, isolated and time-deprived we are, the more likely we are to turn to paid personal services. To finance these extra services, we work longer hours. This leaves less time to spend with family, friends and neighbors; we become less likely to call on them for help, and they on us. And, the more we rely on the market, the more hooked we become on its promises.

In the end, Hochschild sums up, offering a warning about outsourcing our personal lives and emotional attachment:

Focusing attention on the destination, we detach ourselves from the small — potentially meaningful — aspects of experience. Confining our sense of achievement to results, to the moment of purchase, so to speak, we unwittingly lose the pleasure of accomplishment, the joy of connecting to others and possibly, in the process, our faith in ourselves.

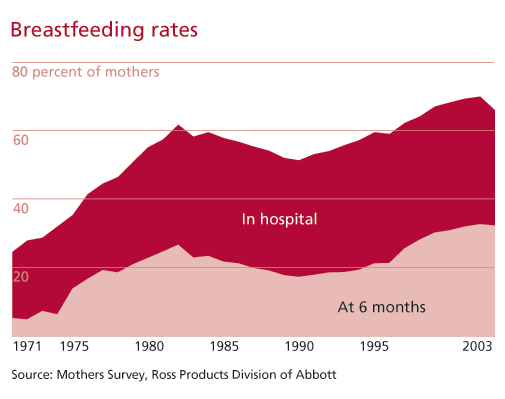

Later in the week, the Times featured Princeton professor Elizabeth Armstrong discussing the harmful effects of distributing free baby formula samples to new mothers at hospitals. In her op-ed, Armstrong maintains that breast-feeding offers many health benefits to babies, and hospitals should be encouraging women in the practice (she makes no mention of whether “Macho Mothering” like that featured on the controversial cover of TIME will help or hinder such efforts). When hospitals give away formula samples, reports show women are more likely to give up breast-feeding sooner. According to Armstrong, though, it’s easy to see why the hospitals continue to provide the samples:

In exchange for giving out samples, formula manufacturers provide hospitals’ nurseries and neonatal intensive care units with much needed free supplies like bottles, nipples, pacifiers, sterile water and more formula.

Armstong argues that arrangement like these lead to a hypocritical healthcare system. Doctors and medical organizations can preach about the benefits of breast-feeding but when “hospitals send new mothers home with a commercial product that often bears scientific claims on the label about digestion and brain development, it sends a very different message.” For Armstong, the answer is simple:

[H]ospitals should help women get breast-feeding off to a good start by adapting baby-friendly policies like helping mothers initiate breast-feeding after birth, allowing mothers and babies to stay in the same room and, most important, ensuring that infant-feeding decisions are free of commercial influence.

Each of these pieces is a great example of a sociologist putting their own work out into the world in a way that allows everyone to see the benefits of sociological insight and its application to, well, society. Congrats to both professors for so frequently daring to peek out from the pages of journals.

For more on breast-feeding and public service efforts to encourage it, we recommend Julie Artis’ Contexts article “Breastfeed at your own Risk,” available in full online at Contexts.org.

Comments 3

Sociologists Take the Times – Alex Casey « anagnori — May 15, 2012

[...] Sociologists Take the Times – Alex Casey – The Society Pages [...]

Dana — May 16, 2012

Great article! Hospitals shouldn't give out free infant formula packages because they have been shown to discourage breastfeeding. Even though these samples are initially “free,” they end up costing more because mothers are likely to stick with the particular brand they receive in hospitals. These can cost up to $700 per year more than the cheaper alternative brands.

And, more importantly, there is consensus among all major health care providers that exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months after a child is born is best for the health of both infants and mothers. Children who are not breastfed are more prone to medical problems, including severe lower respiratory tract infections, obesity, diabetes, childhood leukemia and more.

The infant formula industry makes its profits by ensuring that less women breastfeed their babies. At least two-thirds of hospitals in the U.S. distribute samples of infant formula, even if mothers have indicated that they plan to breastfeed. Hospitals should stop serving as marketing platforms for infant formula companies and start educating new mothers about the full range of feeding options. When formula is necessary, women should be able to decide for themselves which brand to use.

http://www.citizen.org/pressroom/pressroomredirect.cfm?ID=3578

Belatedly, the May 2012 Media Award for Measured Social Science » Citings and Sightings — August 22, 2012

[...] of Arlie Russell Hochschild’s The Outsourced Self (the author was the subject of her own Citing in May 2012 with a New York Times Op-Ed), Shulevitz wrote: I guess you’d call it popular sociology, [...]