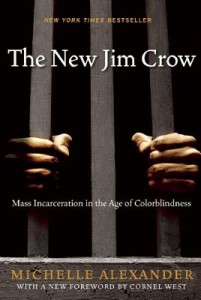

As part of its programming surrounding our national day of remembrance in honor of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., NPR’s Fresh Air brought scholar Michelle Alexander to the airwaves last night for a lengthy, fascinating interview. Alexander is the author of the book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (out now in paperback with an introduction by Cornel West), and she argues persuasively that, as NPR puts it, “Jim Crow laws are now off the books [but] millions of blacks… remain marginalized and disenfranchised… denied [the] basic rights and opportunities that would allow them to become productive, law-abiding citizens.”

As part of its programming surrounding our national day of remembrance in honor of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., NPR’s Fresh Air brought scholar Michelle Alexander to the airwaves last night for a lengthy, fascinating interview. Alexander is the author of the book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (out now in paperback with an introduction by Cornel West), and she argues persuasively that, as NPR puts it, “Jim Crow laws are now off the books [but] millions of blacks… remain marginalized and disenfranchised… denied [the] basic rights and opportunities that would allow them to become productive, law-abiding citizens.”

President Reagan’s “War on Drugs,” was declared, Alexander said, “primarily for reasons of politics—racial politics. … [these] racially coded ‘get-tough’ appeals on issues of crime and welfare appeal to poor and working-class whites, particularly in the South, who were resentful of, anxious about, and threatened by many of the gains of African Americans in the civil rights movement.” And so, the war on drugs keeps Jim Crow going:

Today there are more African Americans under correctional control—in prison or jail, on probation or parole—than were enslaved in 1850, a decade before the Civil War began. …In major American cities today, more than half of working-age African American men are either under correctional control or branded felons and are thus subject to legalized discrimination for the rest of their lives

In her conversation with Dave Davies, Alexander went on to explain that, while some, like criminologist David Kennedy, believe anyone who’s spent time with those fighting the “War on Drugs” on the streets (that is, who’ve embedded themselves with beat cops and DEA agents) knows there’s absolutely no racial or class bias in who gets arrested for what, she’s found in her research that, for white, middle and upper-class kids, some crimes are considered rites of passage deserving only a slap on the wrist. Just a few miles away, though, in poorer communities of color, those same crimes (particularly the sale and use of recreational drugs, which Alexander says research has found are no more likely among black adolescents than white nor among poor vs. white kids) relegate young people to a life haunted by the legal system.

This, Alexander goes on, is especially problematic in one under-examined way: the disenfranchisement of convicted felons means that these communities, which are already low in political capital (that is, real political power), don’t even have the ability to go and vote for the politicians (and policies) that might improve their lives. “My experience and research has led me to the regrettable conclusion that our system of mass incarceration functions more like a caste system than a system of crime prevention or control,” concludes Alexander.

Comments 1

The Home Stretch (Or: Introducing Our Third Book) » The Editors' Desk — July 9, 2013

[...] The volume will be called Color Lines and Racial Angles, and it will feature about a baker’s dozen of the best pieces on race and diversity that have been developed on our site thus far. You may recall, for example, Jennifer Lee’s piece on “stereotype promise” or Wendy Roth’s article exploring the creation of a “Latino” race. There have been roundtables with distinguished scholars discussing the media and Trayvon Martin in the weeks immediately following his death and the history and future of American immigration, and a few weeks ago we ran a provocative little treatment of the social origins of the term “white trash” by Matt Wray. And waiting patiently in the pipeline are pieces on Native American mascots, diversity discourse, and environmental racism, as well as an interview exchange with Michelle Alexander, author of the prominent and controversial crime and punishment tome The New Jim Crow. [...]