Also, yesterday the Chicago Tribune discussed whether disasters cause people to behave selfishly or altruistically.

Also, yesterday the Chicago Tribune discussed whether disasters cause people to behave selfishly or altruistically.

When the ship is sinking is it really women and children first, or every man for himself? The answer, it seems, may depend on how fast it’s going down.

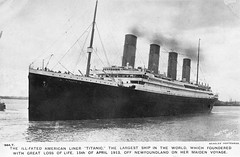

Comparing who survived two of history’s most famous sinkings — the Titanic and the Lusitania — indicates sharply different behavior on the two doomed vessels, neither of which had enough available lifeboats for all passengers.

When a torpedo sent the Lusitania to the bottom in just 18 minutes, claiming 1,198 lives, most survivors were young, fit people age 16 to 35 who could rush to a spot in the lifeboats and hang on to it.

By contrast, it took 2 hours and 40 minutes for the Titanic to slip beneath the waves, time for people to consider what to do rather than just react. While 1,517 people perished, the survivors tended to be women, children and those accompanying a child.

Economist Benno Torgler led a study about how people act in extreme situations. He comments:

“In the environment of the Titanic, social norms were enforced more often, and there was also a higher willingness among males to surrender a seat on a lifeboat,” researcher Benno Torgler of Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia said of the findings.

Why might this be?

Torgler points to the “procreation instinct,” which holds that because the survival of a species depends on its offspring, a high value must be placed upon females of reproductive age as a valuable resource.

Aboard the Titanic, where social norms had time to come into play, women had a 53 percent higher probability of surviving than males, Torgler said. “But no (such) effect was observable in the Lusitania.”

The Titanic went down after colliding with an iceberg on the night of April 12, 1912. It was three years later, May 7, 1915, that a torpedo sank the Lusitania.

The researchers note that it is likely that those aboard the Lusitania were familiar with the Titanic disaster and that also might have affected their thinking more toward self-preservation.

A social psychologist weighs in:

Col. Thomas Kolditz, head of the department of behavioral sciences at the U.S. Military Academy, said the researchers’ explanation for this behavior difference is plausible, “but they underestimate the role of leadership.” Competent leaders in dangerous situations influence people, but this takes time, said Kolditz, who was not part of the research team.

“It is unlikely that the mere passage of time led to the emergence of pro-social and selfless behaviors. It is much more likely that, in the case of the Titanic, leaders were able to impact the process of abandoning ship in a more direct way, whereas the effect of leadership was minimized in the fast-breaking circumstances on the Lusitania,” Kolditz said.

Additionally, social class affected survival chances in these disasters:

The study found a higher survival rate for first-class passengers on the Titanic, but not on the Lusitania, where first-class passengers fared even worse than third-class passengers in the scramble to exit the ship.

In the case of the Titanic, upper class passengers also had more time to assert the privilege to which they were accustomed, calling on the ships officers whom they knew and perhaps even bargaining for seats in the lifeboats.

Comments