Looking for some perspectives on parenting? Here are a few articles to revisit.

In January, Sandra Hofferth presented to CCF a briefing report on Child-Rearing Norms and Practices in Contemporary American Families. Hofferth, Professor, Family Science, at University of Maryland’s School of Public Health, notes that although a recent Census Report had found some differences by family type, most American parents—married, divorced, or single—read to their children, monitor their children’s media youth, and engage their children in extra-curricular activities. Revisit Hofferth’s report here for how parents are doing, by the numbers.

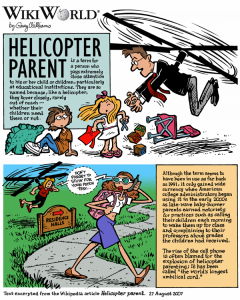

In August, Michelle Janning, a sociologist at Whitman College and CCF Co-Chair, shared a three-part series on parenting: her interest was in overparenting and cross cultural metaphors.

Overprotective Parenting, Back-to-School Edition

American Helicopters, Danish Curling Brooms, and British Lawnmowers