This column was originally posted August 29, 2016, reposting inlight of this news rescinding rules on bathrooms for transgender students.

Why does the federal government think it should tell North Carolina who can use what bathroom? Perhaps one reason is because it seems like a big deal if you can’t go to the bathroom without facing harassment or even the possibility of violence.

In more than 100 interviews for a book I’m finishing on millennials, I heard from many people who had been harassed or had experienced violence in bathrooms. But no story came from a woman harassed by some perverted man disguised as female who had followed her into the restroom.

Harassment in bathrooms is a serious problem, but the new laws enacted to protect North Carolina citizens are protecting the wrong people. House Bill 2 makes the bathrooms less safe for those who really do have to worry about violence.

The stories I heard came from young people who do not conform to gender stereotypes. Fifteen were raised as girls but are not now easily identifiable as men or women. Some are straight and some gay. Women often challenged them if they entered women’s restrooms because they looked boyish. But they were often afraid to enter men’s rooms because they feared violence.

One respondent told me that she did use the men’s room in a bar because she felt it would be easier, as that matched her appearance, but she was followed in and attacked. I have had a former student, a straight heterosexual mother of two who dresses androgynously, tell me she has been harassed entering a women’s room because of her clothing choices.

The six transgender people my team interviewed had experienced so much bullying in restrooms that they were too afraid to use them. They often avoided public bathrooms entirely and developed what one transman told me was a “transbladder.” He had trained himself to hold it for hours, until getting home.

We cannot have a world where women are both equal and still have to be protected from washing their hands next to a man. Sometimes change isn’t comfortable, but it’s still the right thing to do. And guess what, eventually it becomes so comfortable that the next generation can’t imagine what all the fuss was about.

In order to protect these individuals, and still reassure those who might be concerned about harassment going in the other direction, why not simply require every bathroom stall to have a door that locks and, over time, require those doors to reach the floor? After all, in airplanes, homes and coed dorms, everyone uses the same toilets. Indeed, in the university building where I worked this summer as a visiting professor at the University of Trento, there was one restroom on the first floor and a long line of stalls for anyone to use. Indeed, all over Europe I found public toilets with stalls that anyone could use with a shared area to wash one’s hands as well.

The best solution for North Carolina, and the rest of America, is to follow the lead of the airlines, private homes, dormitories and much of Europe. Require all bathrooms to have stalls with locked doors, where only one person sits or stands at a time. Only then will the transgender and gender nonconforming millennials in my research finally be free from bathroom bullies.

I understand that many women find the idea of seeing men’s legs in the next stall disquieting. A sociologist friend recoiled at the idea and couldn’t explain it except to say she just wasn’t “raised that way.” Other women seek the privacy of the washroom to freshen up, to make themselves more attractive to the men they are with. Women, especially those of a certain age, have been raised to want, and need, to retreat from the male gaze.

But it wasn’t so long ago that white Southern ladies just couldn’t imagine sharing a restroom or water fountain with a woman of color, and their men protected them from having to do so. It wasn’t so long ago that police officers’ wives disliked their husbands’ having female partners. It wasn’t so long ago that women were excluded from military units.

We cannot have a world where women are both equal and still have to be protected from washing their hands next to a man. Sometimes change isn’t comfortable, but it’s still the right thing to do. And guess what? Eventually it becomes so comfortable that the next generation can’t imagine what all the fuss was about.

We can learn from what has been happening in college dormitories: men and women living on the same floor with coed bathrooms. I lived in a dorm with coed bathrooms at Boston University in 1973. Forty years ago, coed bathrooms at colleges were radical. Not now. Today college students hardly think twice about it. The future is already here. Just follow the kids.

This column was published originally by the Raleigh News and Observer.

Barbara J. Risman, professor of sociology at the University of Illinois at Chicago, is an Emerita professor at N.C. State University. She is currently vice president of the American Sociological Society and was a 2015-2016 fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University.

For all of its craziness and scariness, the 2016 election campaign has hammered home for millions of Americans the degree to which

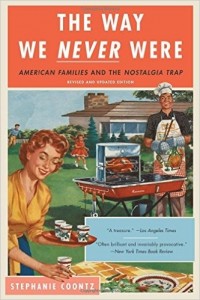

For all of its craziness and scariness, the 2016 election campaign has hammered home for millions of Americans the degree to which  The latest edition of Stephanie Coontz’s

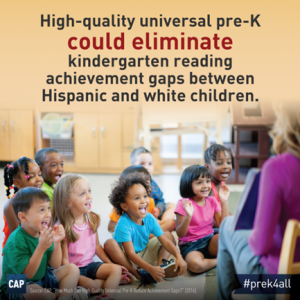

The latest edition of Stephanie Coontz’s  Katherine Gallagher Robbins (@kfgrobbins) is the Director of Family Policy for the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress (CAP). Before joining CAP, Robbins was the director of research and policy analysis at the National Women’s Law Center. Robbins holds a bachelor’s degree in government from the College of William and Mary and a doctorate in political science from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Katherine Gallagher Robbins (@kfgrobbins) is the Director of Family Policy for the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress (CAP). Before joining CAP, Robbins was the director of research and policy analysis at the National Women’s Law Center. Robbins holds a bachelor’s degree in government from the College of William and Mary and a doctorate in political science from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Families at all levels of income are struggling in our economy simply because it does not allow congenial coexistence of work and family life. Lives have become busier and busier and policies have not changed to reflect that. In her book,

Families at all levels of income are struggling in our economy simply because it does not allow congenial coexistence of work and family life. Lives have become busier and busier and policies have not changed to reflect that. In her book,